Cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and subsequently in microwave ovens and in linear particle accelerators.

Electrons pass by the cavities and cause microwaves to oscillate within, similar to the functioning of a whistle producing a tone when excited by an air stream blown past its opening.

The use of magnetic fields as a means to control the flow of an electric current was spurred by the invention of the Audion by Lee de Forest in 1906.

Albert Hull of General Electric Research Laboratory, USA, began development of magnetrons to avoid de Forest's patents,[1] but these were never completely successful.

The development of magnetrons with multiple cathodes was proposed by A. L. Samuel of Bell Telephone Laboratories in 1934, leading to designs by Postumus in 1934 and Hans Hollmann in 1935.

By this time the klystron was producing more power and the magnetron was not widely used, although a 300 W device was built by Aleksereff and Malearoff in the USSR in 1936 (published in 1940).

[1] The cavity magnetron was a radical improvement introduced by John Randall and Harry Boot at the University of Birmingham, England in 1940.

The magnetron continued to be used in radar in the post-war period but fell from favour in the 1960s as high-power klystrons and traveling-wave tubes emerged.

This renders it less suitable for pulse-to-pulse comparisons for performing moving target indication and removing "clutter" from the radar display.

The components are normally arranged concentrically, placed within a tubular-shaped container from which all air has been evacuated, so that the electrons can move freely (hence the name "vacuum" tubes, called "valves" in British English).

It was also noticed that the frequency of the radiation depends on the size of the tube, and even early examples were built that produced signals in the microwave regime.

The original magnetron was very difficult to keep operating at the critical value, and even then the number of electrons in the circling state at any time was fairly low.

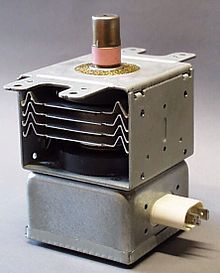

Mechanically, the cavity magnetron consists of a large, solid cylinder of metal with a hole drilled through the centre of the circular face.

All cavity magnetrons consist of a heated cylindrical cathode at a high (continuous or pulsed) negative potential created by a high-voltage, direct-current power supply.

A portion of the radio frequency energy is extracted by a short coupling loop that is connected to a waveguide (a metal tube, usually of rectangular cross section).

The waveguide directs the extracted RF energy to the load, which may be a cooking chamber in a microwave oven or a high-gain antenna in the case of radar.

The magnetron remains in widespread use in roles which require high power, but where precise control over frequency and phase is unimportant.

In practical use these factors have been overcome, or merely accepted, and there are today thousands of magnetron aviation and marine radar units in service.

More modern variants use HEMTs or GaN-on-SiC power semiconductor devices instead of magnetrons to generate the microwaves, which are substantially less complex and can be adjusted to maximize light output using a PID controller.

[27] However, the German military considered the frequency drift of Hollman's device to be undesirable, and based their radar systems on the klystron instead.

This was one reason that German night fighter radars, which never strayed beyond the low-UHF band to start with for front-line aircraft, were not a match for their British counterparts.

[24]: 229 Likewise, in the UK, Albert Beaumont Wood proposed in 1937 a system with "six or eight small holes" drilled in a metal block, differing from the later production designs only in the aspects of vacuum sealing.

GEC at Wembley made 12 prototype cavity magnetrons in August 1940, and No 12 was sent to America with Bowen on the Tizard Mission, where it was shown on 19 September 1940 in Alfred Loomis’ apartment.

[31] According to Andy Manning from the RAF Air Defence Radar Museum, Randall and Boot's discovery was "a massive, massive breakthrough" and "deemed by many, even now [2007], to be the most important invention that came out of the Second World War", while professor of military history at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, David Zimmerman, states: The magnetron remains the essential radio tube for shortwave radio signals of all types.

It not only changed the course of the war by allowing us to develop airborne radar systems, it remains the key piece of technology that lies at the heart of your microwave oven today.

[5] An early 10 kW version, built in England by the General Electric Company Research Laboratories in Wembley, London, was taken on the Tizard Mission in September 1940.

[5] In late 1941, the Telecommunications Research Establishment in the United Kingdom used the magnetron to develop a revolutionary airborne, ground-mapping radar codenamed H2S.

Centimetric contour mapping radars like H2S improved the accuracy of Allied bombers used in the strategic bombing campaign, despite the existence of the German FuG 350 Naxos device to specifically detect it.

Most magnetrons contain a small amount of beryllium oxide[citation needed] for the insulators, and thorium mixed with tungsten in their filament.

Exceptions to this are higher power magnetrons that operate above approximately 10,000 volts where positive ion bombardment becomes damaging to thorium metal, hence pure tungsten (potassium doped) is used.