Celebrant (Australia)

However Australia was the first nation whose government appointed non-clergy celebrants with the intention of creating ceremonies which aspire to be as culturally enriching and, if required, as formal, as church weddings.

Civil celebrants also serve people with religious beliefs but who do not wish to be married in a place of worship or by a clergy person.

Thus, the civil celebrant has the role of a professionally trained ceremony provider who works in accordance with the wishes of the client couple and advises them.

Murphy himself told me the story of how he was opposed by his own staff, the public service, his fellow members of parliament and officials of the Labour Party.

Lois D'Arcy, in a 1992 address to celebrants, recollected Murphy's own account of his authorising the first appointment: [Lionel had] returned to his office one evening.

High Court Justice Michael Kirby remarked in 2000: Lionel Murphy was a big figure on the stage of Australian public life.

According to Messenger and D'Arcy (opera.cit), the pioneer civil celebrants knew they were part of a radical and innovative cultural change.

[13][15] From 19 July 1973 Lionel Murphy and Australia led the Western world in establishing ceremonies of meaning and substance for secular people.

And originally, civil celebrants were instructed that the readings, ideals, values, vows, music (lyrics) which are expressed, must be secular and non-religious.

He appointed a well-known model, Jill-Ellen Fuller, as the inaugural president of the Australian Civil Marriage Celebrants Association (ACMCA).

[13] Apart from survival, the main activities of the ACMCA became to deal with the media, and to distribute and share (by mail) resources among the celebrants i.e. poems and quotations, for use in ceremonies.

[13] Despite a number of difficulties and problems, the civil celebrant program turned out to be hugely popular with the general public.

Realising they received the same remuneration if they spent time and care in the preparation of a marriage, or if they did not, many provided the absolute minimum for the marrying couple.

To make matters worse, the fixed fee, in a period of high inflation, declined in value, which further exacerbated the problem.

Despite Lionel Murphy's clear declarations to the contrary, some powerful public servants began to classify the office of marriage celebrant as a "community service" which led to a further deterioration of professional standards.

Funeral and Naming ceremonies, originally opposed by the majority of celebrants and the Attorney-General's Department, had gradually and imperceptibly become accepted.

Other activists at this time included Ken Woodburn, Lyn Knorr, Beverley Silvius, Gavan Grosser, Cavell Ferrier and Brian and Tina McInerney.

They also devised a plan for regular meetings and conferences to encourage co-operation, professional development, and to focus on a deeper understanding of the role of the celebrant in society.

[35] Their most important decision was to mount a political and media campaign to abolish the fixed fee, perceived as the cause of the lowest standards since the program was established.

With the assistance of leading constitutional lawyer, Professor Michael Pryles, and the abovementioned media publicity, the government responded.

More importantly, a search conference, initiated by public servant, Helen Eastburn, was set up to establish Competency Standards under Jan Wallbridge and Jennifer Rivers of the Canberra Institute of Technology.

A watershed of development and possibly symbolically expressing the most profound maturing within the celebrant movement were the series of conferences held at Pallotti College, Millgrove, northeast of Melbourne from 1994 to 1999.

[37] Thirty years later, following an extensive review and the introduction of reforms by the federal Attorney-General Daryl Williams, the marriage celebrant system changed.

In this same month a series of legal and administrative changes to the civil celebrant program were put into effect by the Australian Government.

In 2010, Melbourne journalist Mark Russell noted: There are thousands of (rookie marriage celebrants) trying to undercut each other in the race down the aisle.

The number of nuptial nightmares is soaring ... horror stories abound ... inexperienced celebrants have been accused of ruining wedding days because they don't know what they are doing.

On 15 January 2012, in an open letter to Attorney-General Nicola Roxon, nine senior celebrants protested their grievances at the deterioration of the program in which they had formerly felt pride and achievement.

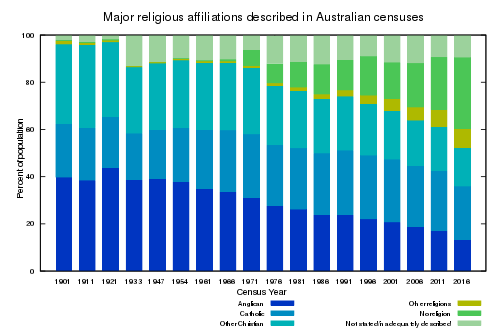

Similarly, statistics of religious marriages only give separate figures for the two largest denominations, Roman Catholics and Anglicans.

This gives the Australian civil marriage celebrant more status than they enjoy in other western countries, but also additional legal responsibility.