Jebel Sahaba

Since their discovery, the skeletons of Jebel Sahaba have been continuously re-evaluated by anthropologists seeking to determine the circumstances of their death.

As of the most recent study (2021), it seems most likely that the war (dating to c. 12th millennium BC) was driven by resource scarcity due to climate change.

The co-occurrence of healed and unhealed lesions among 41 individuals (67.2%) was found to strongly support sporadic and recurrent violence between the social groups of the Nile valley.

[1] It is unclear whether the site is the result of a single conflict, a specific burial place or the evidence of sustained inter-personal violence.

However, a 2021 study treats a possible connection with caution, due to the position of the artefacts, and as other cultural entities were present in Lower Nubia.

The use of points with oblique or transverse distal cutting edges appears to indicate that one of the main lethal properties sought was to slash and cause blood loss.

[7] This salvage dig project was a direct response to the raising of the Aswan Dam which stood to destroy or damage many sites along its path.

[10] Cranial analysis of the Jebel Sahaba fossils found that they shared osteological affinities with a hominid series from Wadi Halfa in Sudan.

[11] Additionally, comparison of the limb proportions of the Jebel Sahaba skeletal remains with those of various ancient and recent series indicated that they were most similar in body shape to the examined modern populations from Sub-Saharan Africa (viz.

In contrast, the paleolithic Iberomaurusian and Natufian remains were showing traits for cold adaptation, and plotting with Europe and Circumpolar regions.

[14] This collection includes skeletal and fauna remains, lithics, pottery, and environmental samples as well as the full archive of Wendorf's notes, slides, and other material during the dig.

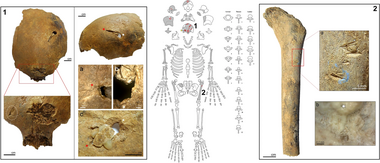

Three cases (those of JS 13 and 14 together, 31, and 44) best illustrate the complexity and range of lesions found in the Jebel Sahaba individuals regardless of their age-at-death, sex or burial.

A further set of marks is visible on the left femur, including two groups of drags on the antero-lateral border of the proximal part of the diaphysis.

[5] The second case, JS 31, focuses on the remains of a probable male over 30 years old based on his heavy dental wear and bone remodeling.

Seventeen lithic artefacts found in situ were in direct association with his skeletal remains, with two embedded in the bone and fifteen within the physical space of the body.

The embedded chips were originally found in the seventh cervical vertebra and in the left pubis, with the bone around both lithics showing severe reactive changes.

The new unhealed PIMs identified include a puncture with crushing, faulting and flaking of the bone surface on the anterior part of the left scapula and a deep V-shaped drag (2 cm long) on the posterior-medial side of the humerus.

The fracture of the left clavicle shaft, located on the acromial end of the diaphysis, reveals a slight torsion and a displacement of the bone fragments.

Given the oblique nature in the forearm and acromial involvement in the clavicle, they may have been caused by an indirect trauma, such as a bad fall, rather than a defensive parry fracture.

[5] In 2001, Wendorf donated all the archives, artefacts and skeletal remains from his 1965–1966 Nile Valley excavations to the British Museum.