Central Asian art

[3][4] The art of ancient and medieval Central Asia reflects the rich history of this vast area, home to a huge variety of peoples, religions and ways of life.

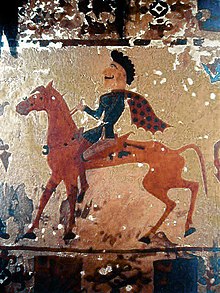

The prehistoric 'animal style' art of these pastoral nomads not only demonstrates their zoomorphic mythologies and shamanic traditions but also their fluidity in incorporating the symbols of sedentary society into their own artworks.

Central Asia has always been a crossroads of cultural exchange, the hub of the so-called Silk Road – that complex system of trade routes stretching from China to the Mediterranean.

Already in the Bronze Age (3rd and 2nd millennium BC), growing settlements formed part of an extensive network of trade linking Central Asia to the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia and Egypt.

[8] The tradition of Upper Paleolithic portable statuettes being almost exclusively European, it has been suggested that Mal'ta had some kind of cultural and cultic connection with Europe during that time period, but this remains unsettled.

Fertility goddesses, named "Bactrian princesses", made from limestone, chlorite and clay reflect agrarian Bronze Age society, while the extensive corpus of metal objects point to a sophisticated tradition of metalworking.

[11] Wearing large stylised dresses, as well as headdresses that merge with the hair, "Bactrian princesses" embody the ranking goddess, character of the central Asian mythology that plays a regulatory role, pacifying the untamed forces.

Many of the Pazyryk felt hangings, saddlecloths, and cushions were covered with elaborate designs executed in appliqué feltwork, dyed furs, and embroidery.

Of exceptional interest are those with animal and human figural compositions, the most notable of which are the repeat design of an investiture scene on a felt hanging and that of a semi-human, semi-bird creature on another (both in the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg).

Many of the trappings took the form of iron, bronze, and gilt wood animal motifs either applied or suspended from them; and bits had animal-shaped terminal ornaments.

Altai-Sayan animals frequently display muscles delineated with dot and comma markings, a formal convention that may have derived from appliqué needlework.

Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian civilisation of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.

[31] Margiana and Bactria belonged to the Medes for a time, and were then annexed to the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great in sixth century BC, forming the twelfth satrapy of Persia.

[35] In addition, Xerxes also settled the "Branchidae" in Bactria; they were the descendants of Greek priests who had once lived near Didyma (western Asia Minor) and betrayed the temple to him.

[40][43] Numerous artefacts and structures were found, particularly in Ai-Khanoum, pointing to a high Hellenistic culture, combined with Eastern influences, starting from the 280–250 BC period.

Various sculptural fragments were also found at Ai-Khanoum, in a rather conventional, classical style, rather impervious to the Hellenizing innovations occurring at the same time in the Mediterranean world.

Of special notice, a huge foot fragment in excellent Hellenistic style was recovered, which is estimated to have belonged to a 5–6 meter tall statue (which had to be seated to fit within the height of the columns supporting the Temple).

[47][48] Due to the lack of proper stones for sculptural work in the area of Ai-Khanoum, unbaked clay and stucco modeled on a wooden frame were often used, a technique which would become widespread in Central Asia and the East, especially in Buddhist art.

A variety of artefacts of Hellenistic style, often with Persian influence, were also excavated at Ai-Khanoum, such as a round medallion plate describing the goddess Cybele on a chariot, in front of a fire altar, and under a depiction of Helios, a fully preserved bronze statue of Herakles, various golden serpentine arm jewellery and earrings, a toilet tray representing a seated Aphrodite, a mold representing a bearded and diademed middle-aged man.

An almost life-sized dark green glass phallus with a small owl on the back side and other treasures are said to have been discovered at Ai-Khanoum, possibly along with a stone with an inscription, which was not recovered.

Various sculptures and friezes are known, representing horse-riding archers, and, significantly, men with artificially deformed skulls, such as the Kushan prince of Khalchayan (a practice well attested in nomadic Central Asia).

[58] A monumental sculpture of King Kanishka I has been found in Mathura in northern India, which is characterized by its frontality and martial stance, as he holds firmly his sword and a mace.

The Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom (also called "Kushanshas" KΟÞANΟ ÞAΟ Koshano Shao in Bactrian[65]) is a historiographic term used by modern scholars[66] to refer to a branch of the Sasanian Persians who established their rule in Bactria and in northwestern Indian subcontinent (present day Pakistan) during the 3rd and 4th centuries AD at the expense of the declining Kushans.

[116] monumental statues of Gautama Buddha carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley of central Afghanistan, 130 kilometres (81 mi) northwest of Kabul at an elevation of 2,500 metres (8,200 ft).

[117] The statues consisted of the male Salsal ("light shines through the universe") and the (smaller) female Shamama ("Queen Mother"), as they were called by the locals.

[120] From the 3rd century AD, the Tarim Basin became a centre for the development of Buddhist art, and a major relay for the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism.

[135] In addition to revealing aspects of their social and political lives, Sogdian art has also been instrumental in aiding historians' understanding of their religious beliefs.

At Zhetysu, Sogdian gilded bronze plaques on a Buddhist temple show a pairing of a male and female deity with outstretched hands holding a miniature camel, a common non-Buddhist image similarly found in the paintings of Samarkand and Panjakent.

At its greatest extent, the Seljuk Empire controlled a vast area stretching from western Anatolia and the Levant to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf in the south.

At its height in the late 13th century, the khanate extended from the Amu Darya south of the Aral Sea to the Altai Mountains in the border of modern-day Mongolia and China, roughly corresponding to the defunct Qara Khitai Empire.