Central venous catheter

Placement of larger catheters in more centrally located veins is often needed in critically ill patients, or in those requiring prolonged intravenous therapies, for more reliable vascular access.

[1][2] The catheters used are commonly 15–30 cm in length, made of silicone or polyurethane, and have single or multiple lumens for infusion.

[3] Relative contraindications include: coagulopathy, trauma or local infection at the placement site, or suspected proximal vascular injury.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) and other medical organizations recommend the routine use of ultrasonography to minimize complications.

Accidental cannulation of the carotid artery is a potential complication of placing a central line in the internal jugular vein.

[8] The problem of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) has gained increasing attention in recent years.

[10] CLABSI is also associated with longer intensive care unit and hospital stays, at 2.5 and 7.5 days respectively when other illness related factors are adjusted for.

[12] Evidence suggests that there may not be any benefit associated with giving antibiotics before a long-term central venous catherter is inserted in cancer patients and this practice may not prevent gram positive catheter-related infections.

[13] However, for people who require long-term central venous catheters who are at a higher risk of infection, for example, people with cancer who at are risk of neutropenia due to their chemotherapy treatment or due to the disease, flushing the catheter with a solution containing an antibiotic and heparin may reduce catheter-related infections.

[13] In a clinical practice guideline, the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against routine culturing of central venous lines upon their removal.

[10] Patient specific risk factors for the development of catheter-related bloodstream infections include placing or maintaining a central catheter in those who are immunocompromised, neutropenic, malnourished, have severe burns, have a body mass index greater than 40 (obesity) or if a person has a prolonged hospital stay before catheter insertion.

[3] Anti-clotting drugs such as heparin and fondaparinux have been shown to decrease the incidence of blood clots, specifically deep vein thrombosis, in a person with cancer with central lines.

Infusates that contain a significant amount of lipids such as total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or propofol are also prone to occlusion over time.

[3] CVC misplacement is more common when the anatomy of the person is different or difficult due to injury or past surgery.

[26] The tip of the catheter can also be misdirected into the contralateral (opposite side) subclavian vein in the neck, rather than into the superior vena cava.

It mostly occurs in the upper extremities and can lead to further complications, such as pulmonary embolism, post-thrombotic syndrome, and vascular compromise.

Symptoms include pain, tenderness to palpation, swelling, edema, warmth, erythema, and development of collateral vessels in the surrounding area.

[30][31] Before insertion, the patient is first assessed by reviewing relevant labs and indication for CVC placement, in order to minimize risks and complications of the procedure.

Within North America and Europe, ultrasound use now represents the gold standard for central venous access and skills, with diminishing use of landmark techniques.

[1] A chest X-ray may be performed afterwards to confirm that the line is positioned inside the superior vena cava and no pneumothorax was caused inadvertently.

[37] Electromagnetic tracking can be used to verify tip placement and provide guidance during insertion, obviating the need for the X-ray afterwards.

[28] PICC lines may also result in venous thrombosis and stenosis, and should therefore be used cautiously in patients with chronic kidney disease in case an arteriovenous fistula might one day need to be created for hemodialysis.

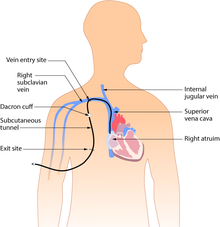

The exit site is typically located in the chest, making the access ports less visible than catheters that protrude directly from the neck.

Insertion is a surgical procedure, in which the catheter is tunneled subcutaneously under the skin in the chest area before it enters the SVC.

Surgically implanted infusion ports are placed below the clavicle (infraclavicular fossa), with the catheter threaded into the heart (right atrium) through a large vein.

Once implanted, the port is accessed via a "gripper" non-coring Huber-tipped needle (PowerLoc is one brand, common sizes are 0.75 and 1 inch (19 and 25 mm) length; 19 and 20 gauge.

As ports are located completely under the skin, they are easier to maintain and have a lower risk of infection than CVC or PICC catheters.

[1] An implanted port is less obtrusive than a tunneled catheter or PICC line, requires little daily care, and has less impact on the patient's day-to-day activities.

Ports are typically used on patients requiring periodic venous access over an extended course of therapy, then flushed regularly until surgically removed.

[43] Certain lines are impregnated with antibiotics, silver-containing substances (specifically silver sulfadiazine) and/or chlorhexidine to reduce infection risk.

- Syringe with local anesthetic

- Scalpel

- Sterile gel for ultrasound guidance

- Introducer needle (here 18 Ga ) on syringe with saline to detect backflow of blood upon vein penetration

- Guide wire

- Tissue dilator

- Indwelling catheter (here 16 Ga )

- Additional fasteners, and corresponding surgical thread

- Dressing