Cesare Beccaria

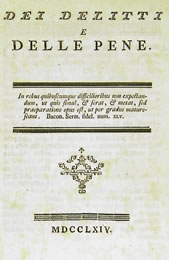

He is well remembered for his treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764), which condemned torture and the death penalty, and was a founding work in the field of penology and the classical school of criminology.

[8] In his mid-twenties, Beccaria became close friends with Pietro and Alessandro Verri, two brothers who with a number of other young men from the Milan aristocracy, formed a literary society named "L'Accademia dei pugni" (the Academy of Fists), a playful name which made fun of the stuffy academies that proliferated in Italy and also hinted that relaxed conversations which took place in there sometimes ended in affrays.

Through this group Beccaria became acquainted with French and British political philosophers, such as Diderot, Helvétius, Montesquieu, and Hume.

In this essay, Beccaria reflected the convictions of his friends in the Il Caffè (Coffee House) group, who sought reform through Enlightenment discourse.

Morellet felt the Italian text required clarification, and therefore omitted parts, made some additions, and above all restructured the essay by moving, merging or splitting chapters.

Throughout his work, Beccaria develops his position by appealing to two key philosophical theories: social contract and utility.

Concerning utility (perhaps influenced by Helvetius), Beccaria argues that the method of punishment selected should be that which serves the greatest public good.

He defends his view about the temporal proximity of punishment by appealing to the associative theory of understanding in which our notions of causes and the subsequently perceived effects are a product of our perceived emotions that form from our observations of a causes and effect occurring in close correspondence (for more on this topic, see David Hume's work on the problem of induction, as well as the works of David Hartley).

Beccaria had elaborated this original principle in conjunction with Pietro Verri, and greatly influenced Jeremy Bentham to develop it into the full-scale doctrine of Utilitarianism.

He openly condemned the death penalty on two grounds: Beccaria developed in his treatise a number of innovative and influential principles: He also argued against gun control laws,[11] and was among the first to advocate the beneficial influence of education in lessening crime.

He further wrote, "[These laws] certainly makes the situation of the assaulted worse, and of the assailants better, and rather encourages than prevents murder, as it requires less courage to attack unarmed than armed persons".

[13] As Beccaria's ideas were critical of the legal system in place at the time, and were therefore likely to stir controversy, he chose to publish the essay anonymously, for fear of government backlash.

Catherine the Great publicly endorsed it, while thousands of miles away in the United States, founding fathers Thomas Jefferson and John Adams quoted it.

However, the chronically-shy Beccaria made a poor impression and left after three weeks, returning to Milan and to his young wife Teresa and never venturing abroad again.

The break with the Verri brothers proved lasting; they were never able to understand why Beccaria had left his position at the peak of success.

Many reforms in the penal codes of the principal European nations can be traced to the treatise, but few contemporaries were convinced by Beccaria's argument against the death penalty.

His lectures on political economy, which are based on strict utilitarian principles, are in marked accordance with the theories of the English school of economists.

They are published in the collection of Italian writers on political economy (Scrittori Classici Italiani di Economia politica, vols.

[8] Beccaria never succeeded in producing another work to match Dei Delitti e Delle Pene, but he made various incomplete attempts in the course of his life.

Some of the current policies impacted by his theories are truth in sentencing, swift punishment and the abolition of the death penalty in dozens of countries.