Chain gang

The experiment ended after about one year in all states except Arizona,[6] where in Maricopa County inmates can still volunteer for a chain gang to earn credit toward a high school diploma or avoid disciplinary lockdowns for rule infractions.

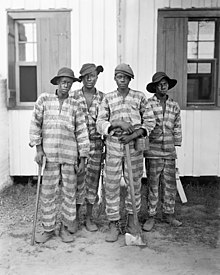

Their distinctive attire (stripe wear or orange vests or jumpsuits) and shaven heads served the purpose of displaying their punishment to the public, as well as making them identifiable if they attempted to escape.

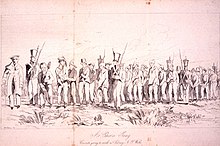

The leg irons were installed by blacksmiths using hot rivets, and then attached to a single "gang chain" to allow for control by an overseer.

[14] The use of iron gangs in the Colony of New South Wales was expanded by Governor Ralph Darling as part of his infrastructure program.

[14] In 1828, the colony's chief surveyor Edmund Lockyer directed that each iron gang could contain up to 60 men, supervised by one main overseer and three assistants.

[16] The use of chain gangs for prison labor was the preferred method of punishment in some Southern states like Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama.

[18] A year after reintroducing the chain gang in 1995, Alabama was forced to again abandon the practice pending a lawsuit from the Southern Poverty Law Center, among other organizations.

In 2011, Tim Hudak, former leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario in Canada, campaigned on introducing penal labour in the province, referred to by many as chain gangs.

According to their own policies, Britain First (a British far-right political organization) want to re-introduce chain gangs "to provide labour for national public works".

[22] In 2013, Brevard County Jail in Sharpes, Florida reintroduced chain gangs as a deterrent on crime in a pilot project.

Instead he proposed a better use of law enforcement resources would be to combat drug addiction because he says it is a "contributing factor" to criminal activity.