Challenger expedition

John Murray, who supervised the publication, described the report as "the greatest advance in the knowledge of our planet since the celebrated discoveries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries".

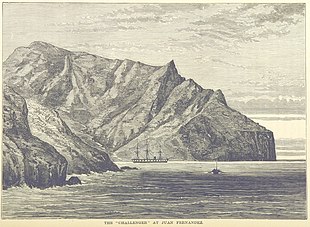

[8] Challenger used mainly sail power during the expedition; the steam engine was used only for dragging the dredge, station-keeping while taking soundings, and entering and leaving ports.

[8] It was loaded with specimen jars, filled with alcohol for preservation of samples, microscopes and chemical apparatus, trawls and dredges, thermometers, barometers, water sampling bottles, sounding leads, devices to collect sediment from the sea bed and great lengths of rope with which to suspend the equipment into the ocean depths.

[8] Challenger reached Hong Kong in December 1874, at which point Nares and Aldrich left the ship to take part in the British Arctic Expedition.

[12] After leaving the Cape Verde Islands in August 1873, the expedition initially sailed south-east and then headed west to reach St Paul's Rocks.

From here, the route went south across the equator to Fernando de Noronha during September 1873, and onwards that same month to Bahia (now called Salvador) in Brazil.

The period from September to October 1873 was spent crossing the Atlantic from Bahia to the Cape of Good Hope, touching at Tristan da Cunha on the way.

[12] December 1873 to February 1874 was spent sailing on a roughly south-eastern track from the Cape of Good Hope to the parallel of 60 degrees south.

February 1874 was spent travelling south and then generally eastwards in the vicinity of the Antarctic Circle, with sightings of icebergs, pack ice and whales.

[12] When the voyage resumed in June 1874, the route went east from Sydney to Wellington in New Zealand, followed by a large loop north into the Pacific calling at Tonga and Fiji, and then back westward to Cape York in Australia by the end of August.

A couple of weeks later, in mid-August, the ship departed south-eastward, anchoring at Hilo Bay off Hawaiʻi Island, before continuing to the south and reaching Tahiti in mid-September.

[12] Most of January 1876 was spent navigating around the southern tip of South America, surveying and touching at many of the bays and islands of the Patagonian archipelago, the Strait of Magellan, and Tierra del Fuego.

From here, the route taken in late April and early May 1876 was a westward loop to the north out into the mid-Atlantic, eventually turning due east towards Europe to touch land at Vigo in Spain towards the end of May.

The final stage of the voyage took the ship and its crew north-eastward from Vigo, skirting the Bay of Biscay to make landfall in England.

[3] The Royal Society stated the voyage's scientific goals were:[13][1] One of the goals of the physical measurements for HMS Challenger was to be able to verify the hypothesis put forward by Carpenter on the link between temperature mapping and global ocean circulation in order to provide some answers on the phenomena involved in the major oceanic mixing.

[14] All these results of physical measurements were synthesized by John James Wild (i.e. the expedition's secretary-artist) in his doctoral thesis at the University of Zurich.

[15] A second important issue concerning the collection of different kinds of physical data on the ocean floor was the laying of submarine telegraph cables.

Mop heads attached to the wooden plank would sweep across the sea floor and release organisms from the ocean bottom to be caught in the nets.

Thomson asked Peter Tait to solve a thorny and important question: to evaluate the error in the measurement of the temperature of deep waters caused by the high pressures to which the thermometers were subjected.

Thomson believed, as did many adherents of the then-recent theory of evolution, that the deep sea would be home to "living fossils" long extinct in shallower waters, examples of "missing links".

They believed that the conditions of constant cold temperature, darkness, and lack of currents, waves, or seismic events provided such a stable environment that evolution would slow or stop entirely.

Thomas Huxley stated that he expected to see "zoological antiquities which in the tranquil and little changed depths of the ocean have escaped the causes of destruction at work in the shallows and represent the predominant population of a past age."

Furthermore, in the process of preserving specimens in alcohol, Thomson and chemist John Young Buchanan realized that he had inadvertently debunked Huxley's prior report of Bathybius haeckelii, an acellular protoplasm covering the sea bottoms, which was purported to be the link between non-living matter and living cells.

[20] As shown by later expeditions using modern equipment, this area represents the southern end of the Mariana Trench and is one of the deepest known places on the ocean floor.

[5] Specimens brought back by Challenger were distributed to the world's foremost experts for examination, which greatly increased the expenses and time required to finalize the report.

[26] A large number of scientists worked on categorizing the material brought back from the expedition including the paleontologist Gabriel Warton Lee.

George Albert Boulenger, herpetologist at the Natural History Museum, named a species of lizard, Saproscincus challengeri, after Challenger.