Chandogya Upanishad

As part of the poetic and chants-focused Samaveda, the broad unifying theme of the Upanishad is the importance of speech, language, song and chants to man's quest for knowledge and salvation, to metaphysical premises and questions, as well as to rituals.

[1][8] Chandogya Upanishad is one of the most cited texts in later Bhasyas (reviews and commentaries) by scholars from the diverse schools of Hinduism, with chapter six verse 8-16 containing the famous dictum Tat Tvam Asi, "that('s how) you are.

[2] Patrick Olivelle states, "in spite of claims made by some, in reality, any dating of these documents (early Upanishads) that attempts a precision closer than a few centuries is as stable as a house of cards".

The first group comprises chapters I and II, which largely deal with the structure, stress and rhythmic aspects of language and its expression (speech), particularly with the syllable Om (ॐ, Aum).

[22] The second volume of the first chapter continues its discussion of syllable Om, explaining its use as a struggle between Devas (gods) and Asuras (demons) – both being races derived from one Prajapati (creator of life).

[25] Max Muller states that this struggle between deities and demons is considered allegorical by ancient scholars, as good and evil inclinations within man, respectively.

[30] The tenth through twelfth volumes of the first "Prapathaka" of Chandogya Upanishad describe a legend about priests and it criticizes how they go about reciting verses and singing hymns without any idea what they mean or the divine principle they signify.

[31][32][33] The verses 1.12.1 through 1.12.5 describe a convoy of dogs who appear before Vaka Dalbhya (literally, sage who murmurs and hums), who was busy in a quiet place repeating Veda.

"[31][35] Such satire is not unusual in Indian literature and scriptures, and similar emphasis for understanding over superficial recitations is found in other ancient texts, such as chapter 7.103 of the Rig Veda.

[36] The text asserts that hāu, hāi, ī, atha, iha, ū, e, hiṅ among others correspond to empirical and divine world, such as Moon, wind, Sun, oneself, Agni, Prajapati, and so on.

[39][40][41] The Chandogya Upanishad states that the reverse is true too, that people call it a-sāman when there is deficiency or worthlessness (ethics), unkindness or disrespect (human relationships), and lack of wealth (means of life, prosperity).

[43] The latter include Hinkāra (हिङ्कार, preliminary vocalizing), Prastāva (प्रस्ताव, propose, prelude, introduction), Udgītha (उद्गीत, sing, chant), Pratihāra (प्रतिहार, response, closing) and Nidhana (निधन, finale, conclusion).

[44] The sets of mapped analogies present interrelationships and include cosmic bodies, natural phenomena, hydrology, seasons, living creatures and human physiology.

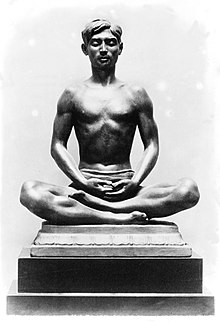

There are three branches of Dharma (religious life, duty): Yajna (sacrifice), Svādhyāya (self study) and Dāna (charity) are the first, Tapas (austerity, meditation) is the second, while dwelling as a Brahmacharya for education in the house of a teacher is third, All three achieve the blessed worlds.

Beyond chronological concerns, the verse has provided a foundation for Vedanta school's emphasis on ethics, education, simple living, social responsibility, and the ultimate goal of life as moksha through Brahman-knowledge.

[64] The Rig hymns, the Yajur maxims, the Sama songs, the Atharva verses and deeper, secret doctrines of Upanishads are represented as the vehicles of rasa (nectar), that is the bees.

[68][69] The first six verses of the thirteenth volume of Chandogya's third chapter state a theory of Svarga (heaven) as human body, whose doorkeepers are eyes, ears, speech organs, mind and breath.

Now Tapas (austerity, meditation), Dāna (charity, alms-giving), Arjava (sincerity, uprightness and non-hypocrisy), Ahimsa (non-violence, don't harm others) and Satya-vacanam (telling truth), these are the Dakshina (gifts, payment to others) he gives [in life].

Paul Deussen states that the underlying message of Samvarga Vidya is that the cosmic phenomenon and the individual physiology are mirrors, and therefore man should know himself as identical with all cosmos and all beings.

King Janasruti is described as pious, extremely charitable, feeder of many destitutes, who built rest houses to serve the people in his kingdom, but one who lacked the knowledge of Brahman-Atman.

[99] Satyakama then learns from these creatures that forms of Brahman is in all cardinal directions (north, south, east, west), world-bodies (earth, atmosphere, sky and ocean), sources of light (fire, Sun, Moon, lightning), and in man (breath, eye, ear and mind).

The boy Satyakama Jabala described in volumes 4.4 through 4.9 of the text, is declared to be the grown up Guru (teacher) with whom Upakosala has been studying for twelve years in his Brahmacharya.

[127] The five householders approach a sage named Uddalaka Aruni, who admits his knowledge is deficient, and suggests that they all go to king Asvapati Kaikeya, who knows about Atman Vaishvanara.

"[132][9] The statement is repeated nine times at the end of sections 6.8 through 6.16 of the Upanishad, स य एषोऽणिमैतदात्म्यमिदँ सर्वं तत्सत्यँ स आत्मा तत्त्वमसि श्वेतकेतोThe traditional translation is "That you are": Yet, according to Brereton, followed by Olivelle and Doniger, the correct translation is "That's how you are": The Tat Tvam Asi dictum emerges in a tutorial conversation between a father and son, Uddalaka Aruni and 24-year-old Śvetaketu Aruneya respectively, after the father sends his boy to study the Vedas, saying "take up the celibate life of a student, for there is no one in our family, my son, who has not studied ad is the kind of Brahmin who is so only because of birth.

[136][135] The commentators[136] to this section of Chandogya Upanishad explain that in this metaphor, the home is Sat (Truth, Reality, Brahman, Atman), the forest is the empirical world of existence, the "taking away from his home" is symbolism for man's impulsive living and his good and evil deeds in the empirical world, eye cover represent his impulsive desires, removal of eye cover and attempt to get out of the forest represent the seekings about meaning of life and introspective turn to within, the knowledgeable ones giving directions is symbolism for spiritual teachers and guides.

[156][157][158] The eighth chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad opens by declaring the body one is born with as the "city of Brahman", and in it is a palace that is special because the entire Universe is contained within it.

[167] The opening passage declares Self as the one that is eternally free of grief, suffering and death; it is happy, serene being that desires, feels and thinks what it ought to.

[174] According to Max Muller, the Chandogya Upanishad is notable for its lilting metric structure, its mention of ancient cultural elements such as musical instruments, and embedded philosophical premises that later served as foundation for Vedanta school of Hinduism.

in his review of the Chandogya Upanishad states, "the opulence of its chapters is difficult to communicate: the most diverse aspects of the [U]niverse, life, mind and experience are developed into inner paths.

[179] The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer admired and often quoted from Chandogya Upanishad, particularly the phrase "Tat tvam asi", which he would render in German as "Dies bist du", and equates in English to “This art thou.”[180][181] One important teaching of Chandogya Upanishad, according to Schopenhauer is that compassion sees past individuation, comprehending that each individual is merely a manifestation of the one will; you are the world as a whole.