Channel Dash

The short route up the English Channel was preferred to a detour around the British Isles for surprise and air cover by the Luftwaffe and on 12 January 1942, Hitler gave orders for the operation.

As dawn arrived the Beaufort flown by Kenneth Campbell attacked and dropped his torpedo as he passed over the mole giving it the maximum distance to arm on its run to its target.

[7] The damage to Gneisenau led the Seekriegsleitung to raise the question of the suitability of Brest for heavy surface units; Raeder disagreed and wanted more air defences instead.

[8] Scharnhorst was not damaged but the bomb hits on the docks delayed its refit, which included a substantial overhaul of its machinery; the boiler superheater tubes had a manufacturing defect that had plagued the ship throughout Operation Berlin.

[9] Repairs had been expected to take ten weeks but delays, exacerbated by British minelaying in the vicinity, caused them to miss Unternehmen Rheinübung (Operation Rhine Exercise).

The loss of Bismarck severely limited the freedom of action of the German surface fleet, after Hitler ordered that capital ships must operate with much greater caution.

[21] Next day Enigma and RAF photographic reconnaissance (PR) found that the number of German ship reinforcements from Brest to the Hook of Holland had risen to seven destroyers, ten torpedo-boats, more than 30 minesweepers, 25 E-boats and many smaller craft.

[22] During 1941, Hitler decided that the Brest Group should return to home waters in a "surprise break through the Channel", as part of a plan to thwart a British invasion of Norway.

OKM preferred the Denmark Strait passage to Germany and Großadmiral (Grand Admiral) Erich Raeder called a journey along the English Channel impossible.

Vice Admiral Otto Ciliax outlined a plan for a standing start at night to gain surprise and to pass the Strait of Dover, 21 mi (34 km) wide and the narrowest part of the Channel, during the day, to benefit from fighter cover at the danger point.

[33] British coastal radar had a range of about 80 nmi (92 mi; 150 km) and with the five standing air patrols, the planners expected a dash up the Channel easily to be discovered, even at night or in bad weather.

On 6 February, HMS Sealion the only modern submarine in home waters, was allowed to sail into Brest Roads, the commander using information supplied through Ultra on minefields, swept channels and training areas.

The six operational Swordfish torpedo-bombers of 825 Squadron FAA (Lieutenant-Commander Eugene Esmonde) were moved from RNAS Lee-on-Solent to RAF Manston in Kent, closer to Dover.

[36] The RAF alerted its forces involved in Operation Fuller to indefinite readiness and on 3 February, 19 Group, Coastal Command began night reconnaissance patrols by Air to Surface Vessel Mk II radar (ASV) equipped Lockheed Hudsons, supposedly able to detect ships at 30 nmi (35 mi; 56 km) range.

The Coastal Command groups were alerted and 42 Squadron was ordered to fly its 14 Beauforts south to Norfolk (the move was delayed until next day by snow on the airfields in East Anglia).

At the patrol height of 1,000–2,000 ft (300–610 m) the ASV had a range of about 13 nmi (15 mi; 24 km) but the Hudson was flying south-west as the ships turned towards Ushant and received no contact.

After they landed at 11:09 a.m., the pilots reported that the German ships had been 16 nmi (18 mi; 30 km) off Le Touquet at 10:42 a.m. by 11:25 a.m., the alarm had been raised that the Brest Group was entering the Straits of Dover with air cover.

[51] The South Foreland Battery of the Dover guns, with their new K-type radar set, tracked the ships of the Brest Group coming up the Channel towards Cap Gris Nez.

[53] The coastal guns ceased fire when light naval forces and torpedo-bombers began to attack and by 1:21 p.m. the German ships passed beyond the effective range of the British radar.

Two more MTBs had left Ramsgate at 12:25 p.m. but approached from too far astern of the German squadron and were unable to get into a position to attack before deteriorating weather and engine problems forced them to turn back.

The Beaufort crews had been briefed that they would be escorted all the way, the fighters that they were to cover the Dover Strait in general and the aircraft circled Manston for thirty minutes, each formation under the impression that another one was leading.

[63] After about thirty minutes, the ship continued at about 25 kn (29 mph; 46 km/h) and as Scharnhorst sailed through the same area, it hit another mine at 9:34 p.m., both main engines stopped, steering was lost and fire control was damaged.

[...] It spelled the end of the Royal Navy legend that in wartime no enemy battle fleet could pass through what we proudly call the English Channel.In 1955, Hans Dieter Berenbrok, a former Kriegsmarine officer, writing under the pseudonym Cajus Bekker, judged the operation a necessity and a success.

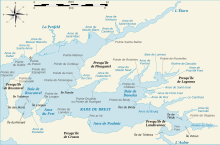

Churchill ordered a Board of Enquiry (under Sir Alfred Bucknill), which criticised Coastal Command for failing to ensure that a dawn reconnaissance was flown to compensate for the problems of the night patrols off Brest and from Ushant to the Isle de Bréhat.

Joubert was criticised for complacency, in not sending replacement sorties, despite his earlier warning that the Brest Group was about to sail, because of the assumption in Operation Fuller since 6 April 1941, that a day sailing was certain, ...a classic example of befuddled tactical thinking, poor co-operation and almost non-existent co-ordination.The Dash exposed many failings in RAF planning, that only three torpedo-bomber squadrons with 31 Beauforts were in Britain, that training had been limited by the lack of torpedoes and the example of Japanese tactics had been ignored.

[76] R. V. Jones, Assistant Director of Intelligence (Science) at the Air Ministry during the war, wrote in his memoir, that for several days, army radar stations on the south coast had been jammed.

Air marshals were said to have sat on each other's desks, thinking of pilots they could telephone to find the ships; even after the Brest Group had been found, contact was lost several times.

[79] In the German semi-official history Germany in the Second World War (2001), Werner Rahn wrote that the operation was a tactical success but that this could not disguise the fact of a strategic withdrawal.

Brest was a location from which the Kriegsmarine had anticipated much success, especially after the Japanese entry into the war had diverted Allied resources to the Pacific, creating new opportunities for offensive action in the Atlantic.

[89] By early 1943, the ship had been sufficiently repaired to begin the conversion but after the failure of German surface forces at the Battle of the Barents Sea in December 1942, Hitler ordered the work to stop.