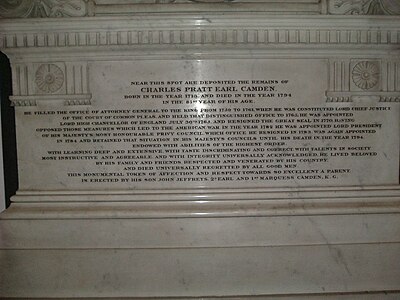

Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden

During his life, Pratt played a leading role in opposing perpetual copyright, resolving the regency crisis of 1788 and championing Fox's Libel Bill.

Born in Kensington in 1714, he was a descendant of an old Devon family of high standing, the third son of Sir John Pratt, Chief Justice of the King's Bench in the reign of George I.

[8] Pratt appeared in Owen's defence and his novel argument was that it was not the sole role of the jury to determine the fact of publication but that it was further their right to assess the intent of a libel.

[4] As Attorney-General, Pratt prosecuted Florence Hensey, an Irishman who had spied for France,[9] and John Shebbeare, a violent party writer of the day.

As evidence of Pratt's moderation in a period of passionate party warfare and frequent state trials, it is notable that this was the only official prosecution for libel that he started[1] and that he maintained his earlier insistence that the decision lay with the jury.

[citation needed] The Common Pleas was not an obvious forum for a jurist with constitutional interest, dealing as it did principally with disputes between private parties.

However, on 30 April 1763, Member of Parliament John Wilkes was arrested under a general warrant for alleged seditious libel in issue No.45 of The North Briton.

The decision earned Pratt some favour with the radical faction in London and seems to have spurred him, over the summer of that year to encourage juries to award disproportionate and excessive damages to printers unlawfully arrested over the same matter.

Pratt pronounced with decisive and almost passionate energy against their legality, thus giving voice to the strong feeling of the nation and winning for himself an extraordinary degree of popularity as one of the maintainers of English civil liberties.

Honours fell thick upon him in the form of addresses from the City of London and many large towns, and of presentations of freedom from various corporate bodies.

Prime Minister Lord Rockingham had unsuccessfully made this, and other appointments, to curry favour with Pitt but Camden was not over-eager to get involved in the crisis surrounding the Stamp Act 1765.

Camden did attend the Commons on 14 January 1766 and his subsequent speeches on the matter in the Lords are so similar to Pitt's that he had clearly adopted the party line.

[4] In May 1766, Pitt again became prime minister and advanced Camden from the court of common pleas to take his seat as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain on 30 July.

In 1768 in the House of Lords he again sat in a case involving John Wilkes, this time rejecting his appeal and finding that his consecutive, rather than concurrent sentences were lawful.

The poor harvest of 1766 led to fears of high grain prices and starvation but parliament was prorogued and could not renew the export ban that expired on 26 August.

Pitt, with Camden's support, called the Privy Council to issue a royal proclamation on 26 September to prohibit grain exports until parliament met.

Benjamin Franklin reportedly observed that it was "internal" taxes that the colonists objected to [citation needed] and Townshend took this to suggest that there would be little opposition to import duties imposed at the ports.

Further, continued unrest in America, stemming from Townshend's 1767 taxation scheme, brought a robust response from Pitt and Camden was his spokesman in the Lords.

[1] Camden opposed Lord Hillsborough's confrontational approach to the Americas, favouring conciliation and working on the development of reformed tax proposals.

Camden personally promised the colonies that no further taxes would be levied, and voted in the cabinet minority who sought to repeal the tea duty.

From 1770 onwards, Chatham neglected parliamentary attendance and left leadership of the house to Lord Shelburne with whom Camden could manage only the coolest of relationships.

In 1774, in the House of Lords appeal in the case of Donaldson v Beckett, Camden spoke against the concept of perpetual copyright for fear of inhibiting the advancement of learning.

Camden roundly criticised the taxes that had led to the American protests, as he had opposed them in Cabinet from 1767 to 1769, but was reminded that he was Lord Chancellor when they were imposed.

It is impossible that this petty island can continue in dependence that mighty continent … To protract the time of separation to a distant day is all that can be hoped.Thomas Hutchinson observed:[4] I never heard a greater flow of words, but my knowledge of facts in this controversy caused his misrepresentations and glosses to appear in a very strong light.How Camden voted on the Quebec Act is unknown but in May 1775, and in response to a petition from a small number of settlers, he unsuccessfully moved its repeal.

However, he seems to have been in the grip of a conspiracy theory that the Act's ulterior objective was to create an army of militant Roman Catholics in Canada to suppress the Protestant British colonists.

[4] He continued steadfastly to oppose the taxation of the American colonists, and signed, in 1778, the protest of the Lords in favour of an address to the King on the subject of the manifesto of the commissioners to America.

[1] In 1782 he was appointed Lord President of the Council under the Rockingham-Shelburne administration, supporting the government economic programme and anti-corruption drive, and championing repeal of the Declaratory Act 1720 in Ireland.

William Pitt the Younger, the son of his former patron, came to power and within a few months, Camden was reinstated as Lord President, holding the post until his death.

[citation needed] To the last, Camden zealously defended his early views on the functions of juries, especially of their right to decide on all questions of libel.

Broadening the legal argument to the constitutional and political Camden charged press freedom to the hands of the jury as the representatives of the people.