Charles Ragon de Bange

He also designed a system of field guns of various calibers which served the French Army well into World War I: the Système de Bange.

Several materials were able to hold the pressure and heat of cannon fire, but did not expand like rubber, thereby failing to provide a tight seal.

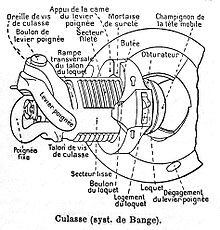

1855 for his rifled muzzle-loading projectiles, where two parts of the shell squeezed a soft (in that case lead) ring under the pressure of gunpowder fumes to obturate the barrel (see Rotation of ammunition), and used a breech block made of three parts; an interrupted screw locking mechanism at the rear, a doughnut-shaped grease-impregnated asbestos pad that sealed the breech, and a rounded movable "nose cone" at the front.

When the gun fired, the nose was driven rearward, compressing the asbestos pad and squeezing it so it expanded outward to seal the breech.

When lifted, the handle operated a cam that forced the breech to rotate counter-clockwise, unlocking the interrupted thread.

This inconvenience would be solved with the appearance of the famous Canon de 75, that had a hydro-pneumatic recoil mechanism, which kept the gun's trail and wheels perfectly still during the firing sequence.