Charles Scott Sherrington

His book The Integrative Action of the Nervous System (1906)[3] is a synthesis of this work, in recognition of which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1932 (along with Edgar Adrian).

During the 1860s the whole family moved to Anglesea Road, Ipswich, reputedly because London exacerbated Caleb Rose's tendency to asthma.

[15] Erling Norrby, PhD, in Nobel Prizes and Notable Discoveries (2016) observed: "His family origin apparently is not properly given in his official biography.

Instead Charles and his two brothers were the illegitimate sons of Caleb Rose, a highly regarded Ipswich surgeon.

"[16] In Ipswich Town: A History, Susan Gardiner writes: "George and William Sherrington, along with their older brother, Charles, were almost certainly the illegitimate sons of Anne Brookes, née Thurtell and Caleb Rose, a leading surgeon from Ipswich, with whom she was living in College Road, Islington at the time that all three boys were born.

No father was named in the baptism register of St James' Church, Clerkenwell, and there is no official record of the registration of any of their births.

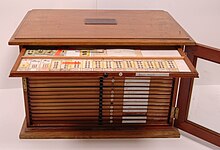

At the family's Edgehill House in Ipswich one could find a fine selection of paintings, books, and geological specimens.

[1][19] Through Rose's interest in the Norwich School of Painters, Sherrington gained a love of art.

Ashe served as an inspiration to Sherrington, instilling a love of classics and the desire to travel.

Sherrington elected to enroll at St Thomas' Hospital in September 1876 as a "perpetual pupil".

[19][22] During June 1875, Sherrington passed his preliminary examination in general education at the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS).

Ferrier's strongest evidence was a monkey who suffered from hemiplegia, paralysis affecting one side of the body only, after a cerebral lesion.

Sherrington performed a histological examination of the hemisphere, acting as a junior colleague to Langley.

Under the auspices of Cambridge University, the Royal Society of London, and the Association for Research in Medicine, a group was put together to travel to Spain to investigate.

[19] Later that year Sherrington travelled to Rudolf Virchow in Berlin to inspect the cholera specimens he procured in Spain.

[25] There, Sherrington worked on segmental distribution of the spinal dorsal and ventral roots, he mapped the sensory dermatomes, and in 1892 discovered that muscle spindles initiated the stretch reflex.

Sherrington's first job of full-professorship came with his appointment as Holt Professor of Physiology at Liverpool in 1895, succeeding Francis Gotch.

Sherrington's work on reciprocal innervation was a notable contribution to the knowledge of the spinal cord.

[19] Sherrington enjoyed the honor of teaching many bright students at Oxford, including Wilder Penfield, who he introduced to the study of the brain.

Several of his students were Rhodes scholars, three of whom – Sir John Eccles, Ragnar Granit, and Howard Florey – went on to be Nobel laureates.

Sherrington's philosophy as a teacher can be seen in his response to the question of what was the real function of Oxford University in the world.

But now with the undeniable upsurge of scientific research, we cannot continue to rely on the mere fact that we have learned how to teach what is known.

He lived at 9 Chadlington Road in north Oxford from 1916 to 1934, and on 28 April 2022 an Oxfordshire blue plaque in his honour was unveiled on this house.

[21] On weekends during the Oxford years the couple would frequently host a large group of friends and acquaintances at their house for an enjoyable afternoon.

[1] Published in 1906,[3] this was a compendium of ten of Sherrington's Silliman lectures, delivered at Yale University in 1904.

[6] The work effectively resolved the debate between neuron and reticular theory in mammals, thereby shaping our understanding of the central nervous system.

[21] The textbook was published in 1919 at the first possible moment after Sherrington's arrival at Oxford and the end of the War.

Sherrington had long studied the 16th century French physician Jean Fernel, and grew so familiar with him that he considered him a friend.

It explores philosophical thoughts about the mind, human existence, and God, in accordance with natural theology.

[1] At the time of his death Sherrington received honoris causa Doctors from twenty-two universities: Oxford, Paris, Manchester, Strasbourg, Louvain, Uppsala, Lyon, Budapest, Athens, London, Toronto, Harvard, Dublin, Edinburgh, Montreal, Liverpool, Brussels, Sheffield, Bern, Birmingham, Glasgow, and the University of Wales.