Charles Thomson

Charles Thomson (November 29, 1729 – August 16, 1824) was an Irish-born Founding Father of the United States and secretary of the Continental Congress (1774–1789) throughout its existence.

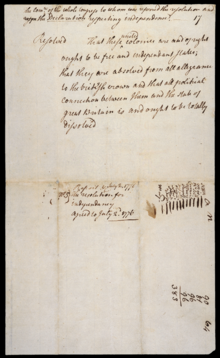

As secretary, Thomson prepared the Journals of the Continental Congress, and his and John Hancock's names were the only two to appear on the first printing of the United States Declaration of Independence.

Thomson is also known for co-designing the Great Seal of the United States and adding its Latin mottoes Annuit cœptis and Novus ordo seclorum, and for his translation of the Bible's Old Testament.

[1][2] After the death of his wife in 1769, John Thomson migrated to the British colonies in North America with his sons (three or four brothers, including Charles).

John Thomson died at sea, his possessions stolen, and the penniless boys were separated on arrival at New Castle, Delaware.

He served as secretary at the 1758 Treaty of Easton and wrote An Enquiry into the Causes of the Alienation of the Delaware and Shawanese Indians from the British Interest (1759), which blamed the war on the proprietors.

Along with John Hancock, the president of the Congress, Thomson's name (as secretary) appeared on the first published version of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776.

[6] Britain's representatives in Paris initially disputed the placement of the Great Seal and Congressional President Thomas Mifflin's signature until they were mollified by Benjamin Franklin.

[7] When designing the final version of the Great Seal, Thomson (a former Latin teacher) kept the pyramid and eye for the reverse side but replaced the two mottos, using Annuit Cœptis instead of Deo Favente (and Novus ordo seclorum instead of Perennis).

James Searle, a delegate and close friend of John Adams, began a cane fight on the floor of Congress against Thomson over a claim that he was misquoted in the minutes that resulted in both men being slashed in the face.

In April, 1789, Thomson was sent by the Senate to the home of George Washington in Virginia to notify him that he had been elected president of the United States.

After leaving office, he chose to destroy the work in an effort to preserve the myths of War of Independence leaders as heroes and stated his desire to avoid "contradict[ing] all the histories of the great events of the Revolution.

The Historical Printing Society publication removes Thomson's notes from the appendix and instead offers them in footnote form throughout the work, according to the original plates to which they refer.