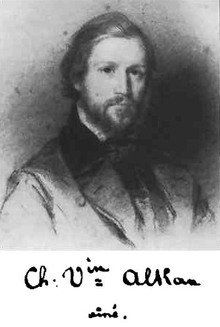

Charles-Valentin Alkan

At the height of his fame in the 1830s and 1840s he was, alongside his friends and colleagues Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, among the leading pianists in Paris, a city in which he spent virtually his entire life.

Although he had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances in the Parisian artistic world, including Eugène Delacroix and George Sand, from 1848 he began to adopt a reclusive life style, while continuing with his compositions – virtually all of which are for the keyboard.

Following his death (which according to persistent but unfounded legend was caused by a falling bookcase), Alkan's music became neglected, supported by only a few musicians including Ferruccio Busoni, Egon Petri and Kaikhosru Sorabji.

[29][30] Alkan twice competed unsuccessfully for the Prix de Rome, in 1832 and again in 1834; the cantatas which he wrote for the competition, Hermann et Ketty and L'Entrée en loge, have remained unpublished and unperformed.

[34] Later in 1834 Alkan made a visit to England, where he gave recitals and where the second Concerto da camera was performed in Bath by its dedicatee Henry Ibbot Field;[35] it was published in London together with some solo piano pieces.

Later that year, Alkan, having found a place of retreat at Piscop outside Paris, completed his first truly original works for solo piano, the Twelve Caprices, published in 1837 as Opp.

[39] From 1837, Alkan lived in the Square d'Orléans in Paris, which was inhabited by numerous celebrities of the time including Marie Taglioni, Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, and Chopin.

[44] At this point, for a period which coincided with the birth and childhood of his natural son, Élie-Miriam Delaborde (1839–1913), Alkan withdrew into private study and composition for six years, returning to the concert platform only in 1844.

[49] Alkan's return to the concert platform in 1844 was greeted with enthusiasm by critics, who noted the "admirable perfection" of his technique, and lauded him as "a model of science and inspiration", a "sensation" and an "explosion".

In the same year he published his piano étude Le chemin de fer, which critics, following Ronald Smith, believe to be the first representation in music of a steam engine.

[52] Following an Alkan recital in 1848, the composer Giacomo Meyerbeer was so impressed that he invited the pianist, whom he considered "a most remarkable artist", to prepare the piano arrangement of the overture to his forthcoming opera, Le prophète.

"[63] Despite his seclusion from society, this period saw the composition and publication of many of Alkan's major piano works, including the Douze études dans tous les tons mineurs, Op.

It may have been associated with the developing career of Delaborde, who, returning to Paris in 1867, soon became a concert fixture, including in his recitals many works by his father, and who was at the end of 1872 given the appointment that had escaped Alkan himself, Professor at the Conservatoire.

[68] The Petits Concerts featured music not only by Alkan but of his favourite composers from Bach onwards, played on both the piano and the pédalier, and occasionally with the participation of another instrumentalist or singer.

This tale, which was circulated by the pianist Isidor Philipp,[75] is dismissed by Hugh Macdonald, who reports the discovery of a contemporary letter by one of his pupils explaining that Alkan had been found prostrate in his kitchen, under a porte-parapluie (a heavy coat/umbrella rack), after his concierge heard his moaning.

The head is strong; the deep forehead is that of a thinker; the mouth large and smiling, the nose regular; the years have whitened the beard and hair ... the gaze fine, a little mocking.

[84] Hugh MacDonald writes that "Alkan's enigmatic character is reflected in his music – he dressed in a severe, old-fashioned, somewhat clerical manner – only in black – discouraged visitors and went out rarely – he had few friends – was nervous in public and was pathologically worried about his health, even though it was good".

"[86] Macdonald, however, suggests that "Alkan was a man of profoundly conservative ideas, whose lifestyle, manner of dress, and belief in the traditions of historic music, set him apart from other musicians and the world at large.

"[95] Alkan's three settings of synagogue melodies, prepared for his former pupil Zina de Mansouroff, are further examples of his interest in Jewish music; Kessous Dreyfuss provides a detailed analysis of these works and their origins.

11 Grands préludes et 1 Transcription (1866), entitled "Alla giudesca" and marked "con divozione", a parody of excessive hazzanic practice;[97] and the slow movement of the cello sonata Op.

[111] Some of his music requires extreme technical virtuosity, clearly reflecting his own abilities, often calling for great velocity, enormous leaps at speed, long stretches of fast repeated notes, and the maintenance of widely spaced contrapuntal lines.

[114] Macdonald suggests that unlike Wagner, Alkan did not seek to refashion the world through opera; nor, like Berlioz, to dazzle the crowds by putting orchestral music at the service of literary expression; nor even, as with Chopin or Liszt, to extend the field of harmonic idiom.

Armed with his key instrument, the piano, he sought incessantly to transcend its inherent technical limits, remaining apparently insensible to the restrictions which had withheld more restrained composers.

Describing this "gigantic" piece, Ronald Smith comments that it convinces for the same reasons as does the music of the classical masters; "the underlying unity of its principal themes, and a key structure that is basically simple and sound.

2, entitled Fa, repeats the note of its title incessantly (in total 414 times) against shifting harmonies which make it "cut ... into the texture with the ruthless precision of a laser beam.

[124] Ronald Smith, however, finds in this latter work, which cites the Dies Irae theme also used by Berlioz, Liszt and others, foreshadowings of Maurice Ravel, Modest Mussorgsky and Charles Ives.

Among the missing works are some string sextets and a full-scale orchestral symphony in B minor, which was described in an article in 1846 by the critic Léon Kreutzer, to whom Alkan had shown the score.

39 as a whole as "a towering achievement, gathering ... the most complete manifestation of Alkan's many-sided genius: its dark passion, its vital rhythmic drive, its pungent harmony, its occasionally outrageous humour, and, above all, its uncompromising piano writing.

[138] The bizarre and unclassifiable Marcia funebre, sulla morte d'un Pappagallo (Funeral march on the death of a parrot, 1859), for three oboes, bassoon and voices, described by Kenneth Hamilton as "Monty-Pythonesque",[139] is also of this period.

In the same year he published a set of very spare and simple preludes in the eight Gregorian modes (1859, without opus number), which, in Smith's opinion, "seem to stand outside the barriers of time and space", and which he believes reveal "Alkan's essential spiritual modesty.