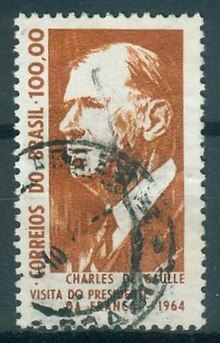

Charles de Gaulle's trip to South America

During this trip of three weeks and 32,000 km,[N 1] the longest made by Charles de Gaulle, he visited Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Brazil.

This trip was motivated by the French president's desire to turn the page on decolonization after the end of the Algerian War in 1962 and to continue his "policy of grandeur" by emphasizing cooperation, in particular by strengthening ties between France and Latin America.

South American elites frequently come to complete their education in France; this is the case of Oscar Niemeyer, the architect of Brasília, or even of Belaunde Terry and Castelo Branco, respectively heads of state of Peru and Brazil, whom de Gaulle met during his diplomatic tour.

On the other hand, his visit to the University of Mexico on March 18 provoked a furore among the public; crowds were so large his car could not continue, and he was "literally carried by clusters of students shouting his name".

The task was difficult, as many parameters had to be reconciled: the length of visits to each country, transport, protocol, security, accommodation, choice of interpreters and Yvonne de Gaulle's specific program.

Most of them, such as Georges Bidault in Brazil, aware of the generous right of asylum they had been granted, did not wish to jeopardize their situation by carrying out actions hostile to de Gaulle.

By emphasizing the use of Spanish in short speeches, simple words, emotion, flattery and repetition, de Gaulle succeeded in making a lasting impression and winning support.

In the General's mind, this refers to the common Latin and Christian civilizational roots linking Europe, and France in particular, to South America, with the United States implicitly excluded.

[12] In response to the welcome address by Venezuelan President Raúl Leoni, he declared "For the first time in history, a French head of state is officially visiting South America".

[N 2][15] During the visit, a government wanted notice was published in the daily El Tiempo concerning Pierre Chateau-Jobert, an OAS leader who had supposedly taken refuge in the country.

"The following day, after paying tribute to the heroes of the Peruvian War of Independence, he was welcomed by the students of San Marcos University to cries of Francia sí, yanquis no ('France yes, Yankees no').

It was therefore decided to move his visit to the city of Cochabamba, at an altitude of 2,570 m.[2] There, President Víctor Paz Estenssoro, elected in 1960, was in trouble; his vice-president, René Barrientos Ortuño, was challenging his authority.

Ambassador Ponchardier described how the French President was welcomed by the crowd, most of whom were Amerindian:[35][36]'In the square in front of the town hall, a motley crew of people in wild clothes and headgear crashed down.

[37] The picturesque nature of this short stopover in Cochabamba seems to have left its mark on the French delegation, as Georges Galichon's wife described it: 'Two rows of horsemen with halberds escorted the General's carriage.

[39] This 900-mile journey southwards along the Chilean coast gave him time to rest and sign a number of laws and decrees, which were published a few days later in the Journal officiel with the words 'Fait à bord du Colbert.

There were strong tensions between Arturo Umberto Illia's government and the supporters of former president Juan Perón, who had been in exile since 1955 and whose banned movement was unable to stand in the elections.

At the Faculty of Law in Buenos Aires, where de Gaulle was due to meet young students, he gave his speech to an audience of public officials who had been summoned to attend in numbers.

Rumours began to circulate among the extreme Catholic right about a de Gaulle-Perón alliance aimed at allowing Perón to return from exile and at jointly pursuing a 'Nasserist' policy favouring the establishment of communism in the country.

The French ambassador Christian de Margerie noted that President Illia's government had emerged from the visit weakened, unable to resolve the issue of reintegrating the Peronists into public life, while the 'military party' was gnawing at its fingernails.

Despite the inclement weather, a large crowd - Le Monde journalists put the number in the hundreds of thousands - lined the route as he made his way to the country's capital.

[27] On 10 October, after a farewell ceremony at the port of call, de Gaulle set sail for Brazil aboard the Colbert, which had crossed the Strait of Magellan from the Pacific to the Atlantic.

Others around the world have identified him with Tito, La Fayette, Ben Bella, Khrushchev, Napoleon, Franco, Churchill, Mao, Nasser, Frederick Barbarossa, not forgetting Joan of Arc and Georges Clemenceau.

[41] However, as Le Monde pointed out, the public welcome varied from one country to another: "friendly without excess in Caracas, fervent and serious in Bogotá, exuberant and unbridled in Quito, curious and distinguished in Lima, moving in Cochabamba.

Chilean President Alessandri, for example, replied to de Gaulle that the country's relations with the United States were "not at all bad" and that it depended heavily on American economic assistance.

[30] Cuba's Castro regime took a very positive view of the French President's trip, and the country's newsreels recounted the visits in detail, with the Cuban ambassador to France simply expressing regret that the Head of State did not stop off in Havana.

[54] Symmetrically, the CIA reported in a document that "in general, de Gaulle drew large and friendly crowds, but in Venezuela and Colombia they were half the size of those during President Kennedy's visit in 1961".

The journalist and historian Paul-Marie de La Gorce also points out, five years after the visit, that "although this policy gave France great prestige in Latin America, repelled by the other European powers, it remained more an intention than a reality".

French companies won the Mexico City metro contract, but there was no follow-up to Franco-Brazilian nuclear cooperation projects and the dispute with Brazil over fishing rights, which had led to the Lobster War, was not resolved.

In a message to German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, he said: "I have returned from my trip to South America convinced that it is up to Europe to play a major role on this continent to which it is attached by so many interests, friendships and traditions".

In the mountains, when we listen to foreign radio stations around the fire in the evening, we are happy to pick up the voice of France, which, although distant, unintelligible for many, and sometimes discordant, nevertheless nourishes hope".