Charlotte Brontë

She became pregnant shortly after her wedding in June 1854 but died on 31 March 1855, almost certainly from hyperemesis gravidarum, a complication of pregnancy which causes excessive nausea and vomiting.

In 1820 her family moved a few miles to the village of Haworth, on the edge of the moors, where her father had been appointed perpetual curate of St Michael and All Angels Church.

[4] She and her surviving siblings – Branwell, Emily and Anne – created this shared world, and began chronicling the lives and struggles of the inhabitants of their imaginary kingdom in 1827.

[7] Charlotte's "predilection for romantic settings, passionate relationships, and high society is at odds with Branwell's obsession with battles and politics and her young sisters' homely North Country realism, none the less at this stage there is still a sense of the writings as a family enterprise".

[16] In "We wove a Web in Childhood" written in December 1835, Brontë drew a sharp contrast between her miserable life as a teacher and the vivid imaginary worlds she and her siblings had created.

In particular, from May to July 1839 she was employed by the Sidgwick family at their summer residence, Stone Gappe, in Lothersdale, where one of her charges was John Benson Sidgwick (1835–1927), an unruly child who on one occasion threw the Bible at Charlotte, an incident that may have been the inspiration for a part of the opening chapter of Jane Eyre in which John Reed throws a book at the young Jane.

During her time in Brussels, Brontë, who favoured the Protestant ideal of an individual in direct contact with God, objected to the stern Catholicism of Madame Héger, which she considered a tyrannical religion that enforced conformity and submission to the Pope.

Their time at the school was cut short when their aunt Elizabeth Branwell, who had joined the family in Haworth to look after the children after their mother's death, died of internal obstruction in October 1842.

It was advertised as "The Misses Brontë's Establishment for the Board and Education of a limited number of Young Ladies" and inquiries were made to prospective pupils and sources of funding.

[22] In May 1846, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne self-financed the publication of a joint collection of poems under their assumed names Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell.

[23] Of the decision to use noms de plume, Charlotte wrote: Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because – without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called "feminine" – we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice; we had noticed how critics sometimes use for their chastisement the weapon of personality, and for their reward, a flattery, which is not true praise.

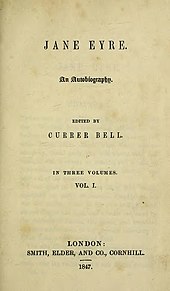

Brontë's first manuscript, 'The Professor', did not secure a publisher, although she was heartened by an encouraging response from Smith, Elder & Co. of Cornhill, who expressed an interest in any longer works Currer Bell might wish to send.

It tells the story of a plain governess, Jane, who, after difficulties in her early life, falls in love with her employer, Mr Rochester.

The book's style was innovative, combining Romanticism, naturalism with gothic melodrama, and broke new ground in being written from an intensely evoked first-person female perspective.

[31] A talented amateur artist, Brontë personally did the drawings for the second edition of Jane Eyre and in the summer of 1834 two of her paintings were shown at an exhibition by the Royal Northern Society for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Leeds.

In September 1848 Branwell died of chronic bronchitis and marasmus, exacerbated by heavy drinking, although Brontë believed that his death was due to tuberculosis.

...The moment is so breathless that dinner comes as a relief to the solemnity of the occasion, and we all smile as my father stoops to offer his arm; for, genius though she may be, Miss Brontë can barely reach his elbow.

Miss Brontë retired to the sofa in the study, and murmured a low word now and then to our kind governess... the conversation grew dimmer and more dim, the ladies sat round still expectant, my father was too much perturbed by the gloom and the silence to be able to cope with it at all... after Miss Brontë had left, I was surprised to see my father opening the front door with his hat on.

He put his fingers to his lips, walked out into the darkness, and shut the door quietly behind him... long afterwards... Mrs Procter asked me if I knew what had happened.

[40] Its main character, Lucy Snowe, travels abroad to teach in a boarding school in the fictional town of Villette, where she encounters a culture and religion different from her own and falls in love with a man (Paul Emanuel) whom she cannot marry.

Another similarity to Jane Eyre lies in the use of aspects of her own life as inspiration for fictional events,[40] in particular her reworking of the time she spent at the pensionnat in Brussels.

Villette was acknowledged by critics of the day as a potent and sophisticated piece of writing although it was criticised for "coarseness" and for not being suitably "feminine" in its portrayal of Lucy's desires.

[41][42] Before the publication of Villette, Brontë received an expected proposal of marriage from Irishman Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father's curate, who had long been in love with her.

Elizabeth Gaskell, who believed that marriage provided "clear and defined duties" that were beneficial for a woman,[46] encouraged Brontë to consider the positive aspects of such a union and tried to use her contacts to engineer an improvement in Nicholls's finances.

"[54] In a letter to Ellen Nussey she wrote: If I could always live with you, and daily read the bible with you, if your lips and mine could at the same time, drink the same draught from the same pure fountain of Mercy – I hope, I trust, I might one day become better, far better, than my evil wandering thoughts, my corrupt heart, cold to the spirit, and warm to the flesh will now permit me to be.

[57] It has been argued that Gaskell's approach transferred the focus of attention away from the 'difficult' novels, not just Brontë's, but all the sisters', and began a process of sanctification of their private lives.

[63] Written in French except for one postscript in English, the letters broke the prevailing image of Brontë as an angelic martyr to Christian and female duties that had been constructed by many biographers, beginning with Gaskell.

[63] The letters, which formed part of a larger and somewhat one-sided correspondence in which Héger frequently appears not to have replied, reveal that she had been in love with a married man, although they are complex and have been interpreted in numerous ways, including as an example of literary self-dramatisation and an expression of gratitude from a former pupil.

[63] In 1980 a commemorative plaque was unveiled at the Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels, on the site of the Madam Heger's school, in honour of Charlotte and Emily.

[64] Kazuo Ishiguro, when asked to name his favourite novelist, answered "Charlotte Brontë's recently edged out Dostoevsky...I owe my career, and a lot else besides, to Jane Eyre and Villette.