Checkers speech

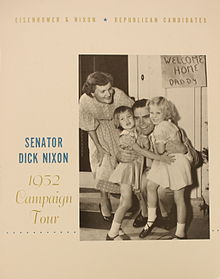

The press became aware of the fund in September 1952, two months after Nixon's selection as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's running mate, and the story quickly grew until it threatened his place on the ticket.

[1] As Smith wrote to one potential contributor, money donated to the Fund was to be used for: Transportation and hotel expenses to cover trips to California more frequently than his mileage allowance permits.

[8] Nixon had campaigned for public integrity in his time in the Senate, even calling for the resignation of his own party chairman, Guy Gabrielson, when the latter was implicated in a loan scandal.

[10] On September 14, Nixon was asked about the Fund by reporter Peter Edson of the Newspaper Enterprise Association after the senator completed an appearance on Meet the Press.

Eisenhower publicly called upon Nixon to release all documents relating to the Fund,[20] somewhat to the dismay of Chotiner, who wondered, "What more does the general require than the senator's word?

[23] When Eisenhower's train stopped for the candidate to make speeches, he faced protesters with signs reading "Donate Here to Help Poor Richard Nixon".

Eisenhower considered asking retired Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts to evaluate the legality of the Fund, but time constraints ruled him out.

The RNC worked to raise the $75,000 (equivalent to $860,000 in 2023) needed to buy the half-hour of television time, while the Eisenhower staff secured sixty NBC stations to telecast the speech, with radio coverage from CBS and Mutual.

[34] When the plane reached Los Angeles, Nixon secluded himself in a suite in The Ambassador Hotel, letting no one except his wife, Chotiner, and attorney and adviser William P. Rogers have any hint what he was planning.

"[38] The morning of the 23rd, the day of the speech, brought the reports from the lawyers,[38] who opined that it was legal for a senator to accept expense reimbursements,[39] and from the accountants, who stated that there was no evidence of misappropriation of money.

Believing they had resolved the situation at last, Eisenhower and his staff had a relaxed dinner and began to prepare for his own speech that evening, before 15,000 Republican supporters in Cleveland.

Nixon replied that it was very late for him to change his remarks; Dewey assured him he need not do so, but simply add at the end his resignation from the ticket and his insistence that Eisenhower accept it.

Dewey suggested he even announce his resignation from the Senate and his intent to run in the special election which would follow—he was sure Nixon would be returned with a huge majority, thus vindicating him.

Chotiner and Rogers would watch from behind a screen in the theatre; Pat Nixon, wearing a dress knitted by supporters, would sit on stage a few feet from her husband.

[47] After stating that the Fund was wrong if he had profited from it, if it had been conducted in secret, or if the contributors received special favors, he continued, Not one cent of the $18,000 or any other money of that type ever went to me for my personal use.

In response to his own question, he detailed his background and financial situation, beginning with his birth in Yorba Linda, and the family grocery store in which the Nixon boys helped out.

He alluded to his work in college and law school, his service record, and stated that at the end of the war, he and Pat Nixon had $10,000 in savings, all of it patriotically in government bonds.

[51] As Chotiner exulted, Nixon moved ahead with the lines "that would give the speech its name, make it famous, and notorious":[52] One other thing I probably should tell you because if we don't they'll probably be saying this about me too, we did get something—a gift—after the election.

"[47] As Nixon made this point, Eisenhower, sitting in the Cleveland office, slammed his pencil down, realizing that he would not be allowed to be the only major party candidate whose finances would evade scrutiny.

Reading parts of a letter from the wife of a serviceman fighting in the Korean War, who, despite her financial woes, had scraped together $10 to donate to the campaign, Nixon promised that he would never cash that check.

Though the Young Republicans continued their applause as the Nixon party left the theatre, he fixed on an Irish Setter running alongside his car as it pulled away from the curb.

The party was able to get through to his suite, and after a few minutes of tense quiet, calls and telegrams began to pour in "from everywhere" praising the speech and urging him to remain on the ticket—but no word came from Eisenhower in Cleveland.

The 15,000 supporters waiting for Eisenhower to speak had heard the Checkers speech over the hall's public address system, and when Congressman George H. Bender took the microphone and asked the crowd, "Are you in favor of Nixon?

[61] Eisenhower's telegram was delayed in transmission and lost among the flood being sent to Nixon's suite, and the latter learned of his running mate's position from a wire service report.

[68] Politicians generally reacted along party lines, with Republican Senator Mundt of South Dakota stating, "Nixon's speech is complete vindication against one of the most vicious smears in American history.

The Baltimore Sun noted that Nixon "did not deal in any way with the underlying question of propriety," while the St. Louis Post-Dispatch called the address "a carefully contrived soap opera".

[74] Columnist Walter Lippmann called the wave of support for Nixon "disturbing ... with all the magnification of modern electronics, simply mob law;"[76] discussing the speech with a dinner guest, he said, "That must be the most demeaning experience my country has ever had to bear.

Governor Stevenson's fund, which proved to total $146,000, had been used for such expenditures as Christmas gifts to reporters, dues for private clubs, and to hire an orchestra for a dance his son was hosting.

[83] However, the onslaught of negative media attention leading up to the address "left its scars" on Nixon,[84] and the future president never returned to the easy relationship with the press that he had enjoyed during his congressional career.

[89] Despite the many criticisms of the speech in later years, Hal Bochin (who wrote a book about Nixon's rhetoric) suggests that Nixon succeeded at the time because of his use of narrative, spinning a story which resonated with the public: [The American people] could identify with the materials of the story—the low-cost apartment, the struggle with the mortgage payment, the parental loans, the lack of life insurance on the wife and children, and even the wife's cloth coat.