African cheetah translocation to India

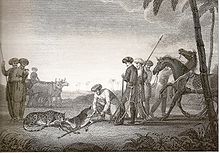

Before the thorn forests in the Punjab region—to the northwest—were cleared for agriculture and human settlement, they were intermixed with open grasslands grazed by large herds of blackbuck; these co-existed with their main natural predator, the Asiatic cheetah.

Offers were made by the government of Kenya beginning in the 1980s but by 2012 the Supreme Court of India had outlawed the project for a species translocation, considering it, in addition, an "introduction" rather than a "reintroduction.

[4][5] On 17 September 2022, five female and three male southeast African cheetahs, between the ages of four and six, were transported by air from Namibia and released in a quarantined enclosure within Kuno National Park in the state of Madhya Pradesh.

The relocation was supervised by Laurie Marker, of the Namibia-based Cheetah Conservation Fund and Yadvendradev Jhala of the Wildlife Institute of India.

Zoologist K. Ullas Karanth has been critical of the effort, conjecturing that potential mortalities might require a continual import of African cheetahs.

Increasing cheetah populations might lead to the animals venturing out of the core zones of the park into adjoining agricultural lands and non-forested areas, bringing them into conflict with humans.

With this in mind, the Supreme Court of India ordered the Indian government to look for alternative parks to accommodate a potentially growing population.

[9] The Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) once ranged from north western India to the Gangetic plain in the east, extending to the Deccan Plateau in the south.

In Punjab in Northern India, before the thorn forests were cleared for agriculture and human settlement, they were intermixed with open grasslands grazed by large herds of blackbuck and these co-existed with their main natural predator, the Asiatic cheetah.

[21] In 1984, wildlife conservationist Divyabhanusinh wrote a paper on the subject on the request of Ministry of Environment and Forests, which was subsequently sent to the Cat Specialist Group of Species Survival Commission of the IUCN.

[22] During the early 2000s, scientists from the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Hyderabad, proposed a plan to clone Asiatic cheetahs from Iran.

[28] The meeting identified Namibia, South Africa, Botswana, Kenya, Tanzania, and the UAE as countries from where the cheetah could be imported to India.

[40][41][42] On 17 September 2022, five female and three male southeast African cheetahs, between the ages of four and six, were flown in from Namibia and released in a quarantined enclosure within the Kuno National Park.

The relocation was supervised by Yadvendradev Jhala of the Wildlife Institute of India and zoologist Laurie Marker, of the Namibia-based Cheetah Conservation Fund.

[55] Following the death of three cheetah cubs, the Central government appointed a high-level steering committee, comprising national and international experts, to oversee the implementation on May 25.

It was based on the postmortem reports which indicated that cheetahs had died of various causes including starvation and infection due to wounds made by the tracking radio collar.

Veterinary pharmacologist Adrian Tordiffe viewed India as providing a "protected space" for the fragmented and threatened cheetah population.

He further commented that the "realities" such as human overpopulation, and the presence of larger feline predators and packs of feral dogs, could cause potentially "high mortalities," and require a continual import of African cheetahs.

Increasing cheetah population leads to the animals venturing out of the core zones of the park into adjoining agricultural lands and non-forested areas, bringing them into conflict with humans.

[73][74] In the same month, the Supreme Court of India ordered the central government to look for an alternative site to augment the existing facility as the park did not have an adequate amount of space for the growing number of felines.

[75][76] According to Ravi Chellam, the introduced African cheetahs had been projected to be a key species of a new phase of ecological restoration in India, comprising scrub forests, savannahs and grasslands.