Common snapping turtle

The present-day Chelydra serpentina population in the Middle Rio Grande suggests that the common snapping turtle has been present in this drainage since at least the seventeenth century and is likely native.

[4] The common snapping turtle is noted for its combative disposition when out of the water with its powerful beak-like jaws, and highly mobile head and neck (hence the specific epithet serpentina, meaning "snake-like").

Lifespan in the wild is poorly known, but long-term mark-recapture data from Algonquin Park in Ontario, Canada, suggest a maximum age over 100 years.

[10] According to a study by Nakamuta et al. (2016), common snapping turtles have well-developed olfactory organs, nerves, and bulbs that suggest that this species has a great sense of smell.

[14] Common snapping turtles sometimes bask—though rarely observed—by floating on the surface with only their carapaces exposed, though in the northern parts of their range, they also readily bask on fallen logs in early spring.

In shallow waters, common snapping turtles may lie beneath a muddy bottom with only their heads exposed, stretching their long necks to the surface for an occasional breath.

[16][17] In a recent study, young common snapping turtles showed that their lower bite force matches their active foraging behavior, meaning they have to travel and seek out more prey to make up for their inability to eat some items.

[18] In some areas adult common snapping turtles can occasionally be incidentally detrimental to breeding waterfowl, but their effect on such prey as ducklings and goslings is frequently exaggerated.

[10] There are records during winter in Canada of hibernating adult common snapping turtles being ambushed and preyed on by northern river otters.

[20] Large, old male common snapping turtles have very few natural threats due to their formidable size and defenses, and tend to have a very low annual mortality rate.

Pollution, habitat destruction, food scarcity, overcrowding, and other factors drive snappers to move; it is quite common to find them traveling far from the nearest water source.

Experimental data supports the idea that common snapping turtles can sense the Earth's magnetic field, which could also be used for such movements (together with a variety of other possible orientation cues).

After digging a hole, the female typically deposits 25 to 80 eggs each year, guiding them into the nest with her hind feet and covering them with sand for incubation and protection.

The common snapping turtle is remarkably cold-tolerant; radiotelemetry studies have shown some individuals do not hibernate, but remain active under the ice during the winter.

Although common snapping turtles have fierce dispositions,[35] when they are encountered in the water or a swimmer approaches, they will slip quietly away from any disturbance or may seek shelter under mud or grass nearby.

Despite this, a common snapping turtle cannot use its claws for either attacking (its legs have no speed or strength in "swiping" motions) or eating (no opposable thumbs), but only as aids for digging and gripping.

There is a large gap behind the back legs that allows for easy grasping of the carapace and keeps hands safe from both the beak and claws of the turtle.

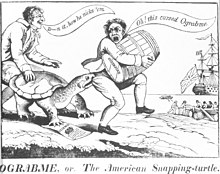

Published in 1808 in protest at the Jeffersonian Embargo Act of 1807, the cartoon depicted a common snapping turtle, jaws locked fiercely to an American trader who was attempting to carry a barrel of goods onto a British ship.

[40] While it is widely rumored that common snapping turtles can bite off human fingers or toes, and their powerful jaws are more than capable of doing so, no proven cases have ever been presented for this species, as they use their overall size and strength to deter would-be predators.

[41] The ability to bite forcefully is extremely useful for consuming hard-bodied prey items such as mollusks, crustaceans, and turtles along with some plant matter, like nuts and seeds.

[42] In 2002, a study reported in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology found that the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) registered between 208 and 226 Newtons of force when it came to jaw strength.

[48] The species is currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, but has declined sufficiently due to pressure from collection for the pet trade and habitat degradation that Canada and several U.S. states have enacted or are proposing stricter conservation measures.