Chemical kinetics

It is different from chemical thermodynamics, which deals with the direction in which a reaction occurs but in itself tells nothing about its rate.

The pioneering work of chemical kinetics was done by German chemist Ludwig Wilhelmy in 1850.

In 1864, Peter Waage and Cato Guldberg published the law of mass action, which states that the speed of a chemical reaction is proportional to the quantity of the reacting substances.

[2][3][4] Van 't Hoff studied chemical dynamics and in 1884 published his famous "Études de dynamique chimique".

[5] In 1901 he was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Chemistry "in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by the discovery of the laws of chemical dynamics and osmotic pressure in solutions".

In consecutive first order reactions, a steady state approximation can simplify the rate law.

Gorban and Yablonsky have suggested that the history of chemical dynamics can be divided into three eras.

[7] The first is the van 't Hoff wave searching for the general laws of chemical reactions and relating kinetics to thermodynamics.

The nature and strength of bonds in reactant molecules greatly influence the rate of their transformation into products.

The physical state (solid, liquid, or gas) of a reactant is also an important factor of the rate of change.

On contact with the saliva in the mouth, these chemicals quickly dissolve and react, releasing carbon dioxide and providing for the fizzy sensation.

Although collision frequency is greater at higher temperatures, this alone contributes only a very small proportion to the increase in rate of reaction.

The effect of temperature on the reaction rate constant usually obeys the Arrhenius equation

, where A is the pre-exponential factor or A-factor, Ea is the activation energy, R is the molar gas constant and T is the absolute temperature.

[8] At a given temperature, the chemical rate of a reaction depends on the value of the A-factor, the magnitude of the activation energy, and the concentrations of the reactants.

The 'rule of thumb' that the rate of chemical reactions doubles for every 10 °C temperature rise is a common misconception.

This involves using a sharp rise in temperature and observing the relaxation time of the return to equilibrium.

In certain organic molecules, specific substituents can have an influence on reaction rate in neighbouring group participation.

In addition to this straightforward mass-action effect, the rate coefficients themselves can change due to pressure.

The rate coefficients and products of many high-temperature gas-phase reactions change if an inert gas is added to the mixture; variations on this effect are called fall-off and chemical activation.

This involves making fast changes in pressure and observing the relaxation time of the return to equilibrium.

The activation energy for a chemical reaction can be provided when one reactant molecule absorbs light of suitable wavelength and is promoted to an excited state.

The study of reactions initiated by light is photochemistry, one prominent example being photosynthesis.

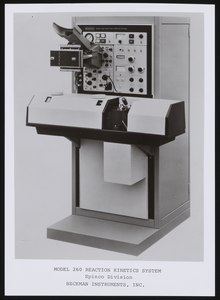

The experimental determination of reaction rates involves measuring how the concentrations of reactants or products change over time.

For reactions which take at least several minutes, it is possible to start the observations after the reactants have been mixed at the temperature of interest.

When performing catalytic cracking of heavy hydrocarbons into gasoline and light gas, for example, kinetic models can be used to find the temperature and pressure at which the highest yield of heavy hydrocarbons into gasoline will occur.

Chemical Kinetics is frequently validated and explored through modeling in specialized packages as a function of ordinary differential equation-solving (ODE-solving) and curve-fitting.

[18] In some cases, equations are unsolvable analytically, but can be solved using numerical methods if data values are given.

Examples of software for chemical kinetics are i) Tenua, a Java app which simulates chemical reactions numerically and allows comparison of the simulation to real data, ii) Python coding for calculations and estimates and iii) the Kintecus software compiler to model, regress, fit and optimize reactions.

To solve the differential equations with Euler and Runge-Kutta methods we need to have the initial values.