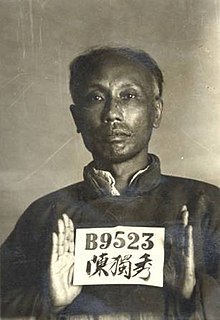

Chen Duxiu

Chen was a leading figure in both the Xinhai Revolution that overthrew the Qing dynasty and the May Fourth Movement for scientific and democratic developments in the early Republic of China.

In order to support overthrowing the Qing government, Chen Duxiu had joined Yue Fei Loyalist Society (岳王會; Yuèwáng huì; Yüeh4-wang2 hui4) which emerged from Gelaohui in Anhui and Hunan province.

Chen was an exceptional student, but his poor experiences taking the Confucian civil service exams resulted in a lifelong tendency to advocate unconventional beliefs and to criticize traditional ideas.

[2] In 1898, he enrolled at Qiushi Academy (now Zhejiang University) in Hangzhou after passing the entrance exam and studied French, English, and naval architecture.

While studying in Japan, Chen helped to found two radical political parties, but refused to join Tongmenghui Revolutionary Alliance, which he regarded as narrowly racist.

Chen was an outspoken writer and political leader by the time of the Wuchang Uprising of 1911, which started the Xinhai Revolution and led to the collapse of the Qing dynasty.

[9] Around that time he was jailed for three months by the Peking authorities for distributing "inflammatory" literature that demanded the resignation of pro-Japanese ministers, and government guarantees for the freedoms of speech and assembly.

At the direction of the Comintern, Chen and the Chinese Communists formed an alliance with Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT or Nationalist Party) in 1922.

The Wuhan government's subsequent land reform policies were considered provocative enough to influence various KMT-aligned generals to attack Wang's regime, suppressing it.

While Chen believed that the focus of revolutionary struggle in China should primarily concern the workers, Mao had started to theorize about the primacy of the peasants.

[3] After the collaboration between the Communist Party and the KMT fell apart in 1927, the Comintern blamed Chen, and systematically removed him from all positions of leadership.

The Chinese Communist Party managed to survive the purges only by fleeing to the northern frontier in the Long March of 1934–1935, during which Mao Zedong emerged as leader.

If only for sheer survival, the Communists had to flee the cities where China's fledgling industrial working class was concentrated, seek refuge in remote rural areas, and there mobilize the support of peasants; this was naturally taken as a vindication of Mao's position in his debate with Chen.

In September Mao responded saying that Chen could rejoin the party if he agreed to publicly renounce Trotskyism and express support for the United Front against Japan.

In poor health and with few remaining friends, Chen Duxiu later retired to Jiangjin, a small town west of Chongqing, where he died in 1942 at the age of 62.

In the Hundred Flowers Campaign, the example of Chen in collaborating with Wang Jingwei's Wuhan government, leading to the ostracism of his peers and the failure of Communist policies at the time, was used by Peng Zhen as a warning never to "forgive" anti-Maoists.

Hong Kong historian Tang Baolin called Hu's verdict on Chen the greatest miscarriage of justice in the Party's history[27] and although his reassessment of Chen has not been officially endorsed by the Party, it was published in 2009 by the Chinese Literature and History Press which is run by the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.

In China, he spent much of his life in the French Concession and the Shanghai International Settlement in order to pursue his writing and scholarly activities free from official harassment.

He also thought that teamwork was very important in journalism, and consequently asked for help from many talented authors and journalists, including Hu Shih and Lu Xun.

On 31 March 1904, Chen founded Anhui Suhua Bao, a newspaper that he established with Fang Zhiwu and Wu Shou in Tokyo to promote revolutionary ideas using vernacular Chinese, which was simple to understand and easy for the general public to read.

After its sixteenth issue, the newspaper added an extra 16 columns; the most popular were on military events, Chinese philosophy, hygiene, and astronomy.

In early 1914, Chen went to Japan, where he worked as an editor and writer in the Tokyo Jiayin Magazine, which was published by Zhang Shizhao.

Having the approval from the Cai Yuanpei, the Chancellor of the Peking University, Chen collected the writings of the students which he appreciated most, which especially included Li Dazhao, Hu Shih, Lu Xun and Qian Yuan.

The magazine began to advocate the use of the scientific method and Logical arguments towards the achievement of political, economic, social, ethical, and democratic goals.

On 27 November 1918, Chen started another magazine, the Weekly Review (每周评论/每週評論) with Li Dazhao in order to criticize the politics of his time in a more direct way and to promote democracy, science, and modern literature.

By publishing newspapers and magazines concerning political issues, Chen provided a channel for the general public to express their ideas or discontent towards the existing government.

At a young age, Chen had already established his first periodical, Guomin Ribao, in which he criticized many social and political problems evident in the late Qing dynasty.

Chen introduced many new ideas into popular Chinese culture, including individualism, democracy, humanism, and the use of the scientific method, and he advocated the abandonment of Confucianism for the adoption Communism.

In its first issue, Chen called for young generation to struggle against Confucianism by "theories of literary revolution" (文学革命论; 文學革命論).

In My Fundamental Opinions written in November 1940, Chen Duxiu wrote about his views concerning democracy, socialism and the Soviet Union.