Genghis Khan

His charismatic personality helped to attract his first followers and to form alliances with two prominent steppe leaders named Jamukha and Toghrul; they worked together to retrieve Temüjin's newlywed wife Börte, who had been kidnapped by raiders.

Kublai's great-grandson Külüg Khan later expanded this title into Fatian Qiyun Shengwu Huangdi (法天啟運聖武皇帝, meaning 'Interpreter of the Heavenly Law, Initiator of the Good Fortune, Holy-Martial Emperor').

[7] The History of Yuan, while poorly edited, provides a large amount of detail on individual campaigns and people; the Shengwu is more disciplined in its chronology, but does not criticise Genghis and occasionally contains errors.

[13] His contemporary Juvayni, who had travelled twice to Mongolia and attained a high position in the administration of a Mongol successor state, was more sympathetic; his account is the most reliable for Genghis Khan's western campaigns.

[19][d] The 1167 dating, favoured by the sinologist Paul Pelliot, is derived from a minor source—a text of the Yuan artist Yang Weizhen—but is more compatible with the events of Genghis Khan's life than a 1155 placement, which implies that he did not have children until after the age of thirty and continued actively campaigning into his seventh decade.

[22] The location of Temüjin's birth, which the Secret History records as Delüün Boldog on the Onon River, is similarly debated: it has been placed at either Dadal in Khentii Province or in southern Agin-Buryat Okrug, Russia.

As the betrothal meant Yesügei would gain a powerful ally and as Börte commanded a high bride price, Dei Sechen held the stronger negotiating position, and demanded that Temüjin remain in his household to work off his future debt.

[37] Around this time, Temüjin developed a close friendship with Jamukha, another boy of aristocratic descent; the Secret History notes that they exchanged knucklebones and arrows as gifts and swore the anda pact—the traditional oath of Mongol blood brothers–at eleven.

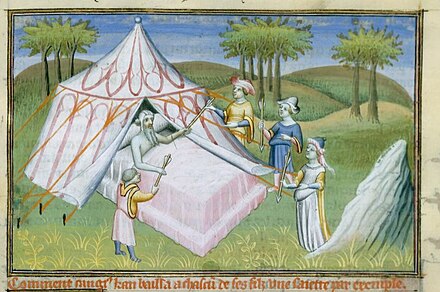

Delighted to see the son-in-law he feared had died, Dei Sechen consented to the marriage and accompanied the newlyweds back to Temüjin's camp; his wife Čotan presented Hö'elün with an expensive sable cloak.

[55] Modern historians such as Ratchnevsky and Timothy May consider it very likely that Temüjin spent a large portion of the decade following the clash at Dalan Baljut as a servant of the Jurchen Jin dynasty in North China.

These included Sorkan-Shira, who had come to his aid previously, and a young warrior named Jebe, who, by killing Temüjin's horse and refusing to hide that fact, had displayed martial ability and personal courage.

[70] A ruse de guerre involving Qasar allowed the Mongols to ambush the Kereit at the Jej'er Heights, but though the ensuing battle still lasted three days, it ended in a decisive victory for Temüjin.

Instead, the descendants of Genghis continued to reign unchallenged, in some cases until as late as the 1700s, and even powerful non-imperial dynasts such as Timur and Edigu were compelled to rule from behind a puppet ruler of his lineage.

In a display of Genghis' meritocratic ideals, many of these men were born to low social status: Ratchnevsky cited Jelme and Subutai, the sons of blacksmiths, in addition to a carpenter, a shepherd, and even the two herdsmen who had warned Temüjin of Toghrul's plans in 1203.

Genghis's attempt to redirect the Yellow River into the city with a dam initially worked, but the poorly-constructed earthworks broke—possibly breached by the Xia—in January 1210 and the Mongol camp was flooded, forcing them to retreat.

[109] Genghis had two aims: to take vengeance for past wrongs committed by the Jin, foremost among which was the death of Ambaghai Khan in the mid-12th century, and to win the vast amounts of plunder his troops and vassals expected.

[111] The three-pronged chevauchée aimed both to plunder and burn a vast area of Jin territory to deprive them of supplies and popular legitimacy, and to secure the mountain passes which allowed access to the North China Plain.

[134] Muhammad's empire was large but disunited: he ruled alongside his mother Terken Khatun in what the historian Peter Golden terms "an uneasy diarchy", while the Khwarazmian nobility and populace were discontented with his warring and the centralisation of government.

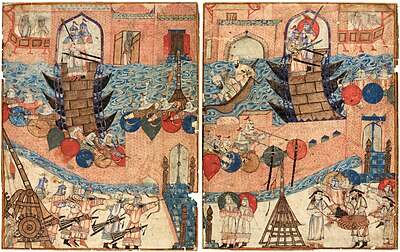

Leaving his sons Chagatai and Ögedei to besiege the city, he had sent Jochi northwards down the Syr Darya river and another force southwards into central Transoxiana, while he and Tolui took the main Mongol army across the Kyzylkum Desert, surprising the garrison of Bukhara in a pincer movement.

[139] Bewildered by the speed of the Mongol conquests, Muhammad fled from Balkh, closely followed by Jebe and Subutai; the two generals pursued the Khwarazmshah until he died from dysentry on a Caspian Sea island in winter 1220–21, having nominated his eldest son Jalal al-Din as his successor.

[142] Jalal al-Din moved southwards to Afghanistan, gathering forces on the way and defeating a Mongol unit under the command of Shigi Qutuqu, Genghis's adopted son, in the Battle of Parwan.

[149] May has disputed this, arguing that the Xia fought in concert with Muqali until his death in 1223, when, frustrated by Mongol control and sensing an opportunity with Genghis campaigning in Central Asia, they ceased fighting.

On 4 December, Genghis decisively defeated a Xia relief army; the khan left the siege of the capital to his generals and moved southwards with Subutai to plunder and secure Jin territories.

[165] Ratchnevsky theorised that the Mongols, who had no knowledge of embalming techniques, may have buried the khan in the Ordos to avoid his body decomposing in the summer heat while en route to Mongolia; Atwood rejects this hypothesis.

[173] Chagatai's attitude towards Jochi's possible succession—he had termed his elder brother "a Merkit bastard" and had brawled with him in front of their father—led Genghis to view him as uncompromising, arrogant, and narrow-minded, despite his great knowledge of Mongol legal customs.

Aware of his own lack of military skill, he was able to trust his capable subordinates, and unlike his elder brothers, compromise on issues; he was also more likely to preserve Mongol traditions than Tolui, whose wife Sorghaghtani, herself a Nestorian Christian, was a patron of many religions including Islam.

These included the halting of all military offensives involving Mongol troops, the establishment of a lengthy mourning period overseen by the regent, and the holding of a kurultai which would nominate successors and select them.

The principal source of steppe wealth was post-battle plunder, of which a leader would normally claim a large share; Genghis eschewed this custom, choosing instead to divide booty equally between himself and all his men.

[210] He sought and gained knowledge of sophisticated weaponry from China and the Muslim world, appropriated the Uyghur alphabet with the help of the captured scribe Tata-tonga, and employed numerous specialists across legal, commercial, and administrative fields.

His unification of the Mongol tribes and his foundation of the largest contiguous state in world history "permanently alter[ed] the worldview of European, Islamic, [and] East Asian civilizations", according to Atwood.