Chevaline

This looked increasingly vulnerable in the face of ever-increasing Soviet Air Defence Forces, and various reports by the RAF suggested their bombers would be incapable of successfully delivering free-fall ("gravity") bombs by 1960.

This had been considered from the early 1950s and the planned solution was a move to the Blue Streak medium range ballistic missile, but this suffered extensive delays for a variety of reasons.

Among many possibilities, the RAF eventually selected the Blue Steel standoff missile to allow its bombers to fire their weapons while still (hopefully) outside the range of the defensive fighters.

The distance from London to Moscow is about 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi), so Skybolt would allow the V-bomber force to attack Russia from sites not far off the British coast, with complete impunity.

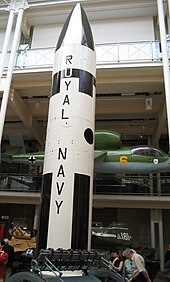

Finally a compromise was reached later that year; the Nassau Agreement had the Royal Navy taking over the deterrent role with newly acquired Polaris missiles.

Developing an ABM system was largely an engineering issue, requiring radars with high resolution and targeting computers that could adjust trajectories fast enough given an approach speed in thousands of miles an hour.

Given that these items would be expensive, the ABM interceptor itself was likely to cost about the same as an ICBM (or less), so any increase in the enemy's stockpile could be countered for an additional expenditure of about the same amount.

An American response was to develop "Antelope", a system designed to overwhelm an ABM defence with decoys, or penaids (penetration aids).

A single Resolution-class submarine with 16 missiles would throw a total of 48 warheads, making it conceivable that many of them might be destroyed by even a small number of ABMs.

The only good news for the UK in this development was that it clearly defined the problem they were facing; their attacks had to be able to credibly defeat a 100-interceptor ABM defence around Moscow.

This would require a fleet of at least five submarines to keep two on station at all times, as well as larger crew complements, training and logistics support, and appeared to be the most expensive option.

In the end the higher levels of the British political system decided against the urgings of their own Chiefs of Staff and went with the penaid approach on the existing A3T missile.

Prompted by a request for a name-change from his boss, the Secretary of State for Defence, Lord Carrington, the official asked the zoo to 'imagine an animal like a large antelope' and inquired whether there was such a beast.

Recent declassifications of official files show that more than half the total project costs were spent in the United States, with industry and government agencies.

This was the source of continuing pressure on the development team from the Naval Staff, who had set the minimum requirement at 2,000 nmi (3,700 km), and who were deeply concerned at intelligence reports of improving Soviet anti-submarine warfare capabilities.

This was a serious problem, because much of NATOs anti-submarine strategy was based on closing the Gap, with the implicit assumption that areas north of it would be fairly easy for Soviet submarines to operate within.

This thermonuclear primary was by then being referred to in official documents as a "trigger device" and some suspect that this new description was a sleight-of-hand to circumvent the pledge given by Prime Minister Wilson of "no new generation of nuclear weapons".

The thermonuclear (or fusion) secondary for Chevaline and known to AWRE by the codename Reggie, is known from these declassified documents to be recycled from the "Unimproved" Polaris A3T warhead.

[7] Although the papers will not be declassified for some time yet, it seems likely that the Naval Staff made the same case with Trident with some success when their influence was at its height after the Falklands War.

The US later decided to move primary development from the C4 to the larger Trident D5, a much more capable missile, but one that would not fit into the latest Ohio-class submarines, let alone the older Benjamin Franklin class.

Finally, recently published recollections from senior members of the development team are explicit in stating that Chevaline was not the best, or with hindsight, the cheapest choice the British could have made from the many options available.

[6] The response to the threat of interception by ABM-1 Galosh missiles was to deploy an upgraded or Improved Front End (IFE) to Polaris A3T using the Antelope/Super Antelope/Chevaline technology.

In the case of an attack on the USSR, even a single Resolution could have ensured the destruction of a significant portion of the Soviet command and control structure.

[citation needed] The 'unimproved' British Polaris A3T carried three 200 kt warheads[8] designated ET.317 in U.S. Mk-2 RVs, composed of a primary known as Jennie and a thermonuclear secondary known as Reggie.

Whilst the fully assembled Chevaline ReB and a new warhead was of identical external shape, and balance to US Polaris RVs to minimise development costs and avoid the need for full-scale flight testing, the Chevaline ReB was unusual in using a new material known as 3-Dimensional Quartz Phenolic (3DQP),[12] which was developed in the UK and subsequently used on US warheads.

The quartz material 'hardens' the ReB protecting the nuclear warhead against high-energy neutrons emitted by exo-atmospheric anti-ballistic missile (ABM) bursts before re-entry.