Chicago Tunnel Company

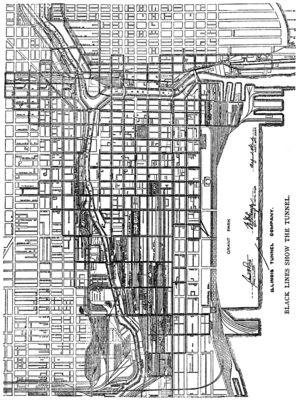

[6] Initially, the intended purpose of the narrow gauge railroad below the telephone cables was limited to hauling out excavation debris and hauling cable spools during the installation of telephone lines,[7] but in 1903, the company renegotiated its franchise to allow the use of this railroad for freight and mail service.

[28] The Interstate Commerce Commission consented to abandonment that July,[29] and the tunnel assets were sold at auction for $64,000 in October.

Should a building catch fire, immense quantities of water could pour into the tunnels through elevator shafts and basement connections.

[34] Official response to the reported leak was slow; no emergency measures were deemed necessary, and a formal bidding process began for the contract to repair the damage.

On April 13, some six months later, the slow oozing of wet clay opened a clear passage from the riverbed, allowing the river to pour directly into the tunnel.

City Hall began to flood by 6:02 am, the Federal Reserve Bank at 8:29 am, finally, the Chicago Hilton and Towers at 12:08 pm.

The long delay before some buildings were flooded was the result of closure of some sections of the tunnel system in 1942 when the passenger subways were built.

[35] Many businesses had not realized that they were still connected to the tunnel complex, as the openings were boarded up, bricked up, or otherwise closed off—but not made watertight.

[36] They have been popular with urban exploration groups who would sometimes sneak in to have a look around, but since the Joseph Konopka terrorism scare in the early 2000s, all access to the tunnels has been secured.

[41] The city asked that the tunnel be built no shallower than 22+1⁄2 feet (6.86 m) below the pavement in order to allow room for a future streetcar subway.

The cars had a box with a capacity of only 0.47 cubic yards (0.36 m3), and were pulled by mules from the tunnel headings to hoists that removed the spoil to the surface[4] or later to points where the spoil could be transferred to 2 ft (610 mm) gauge cars for haulage to the Grant Park disposal station.

There was very little seepage into the tunnels, a natural consequence of excavation in clay, but any water that did find its way in was quickly pumped up to the sewers above.

Ventilation was natural, relying primarily on the piston effect of trains pushing through the tunnels to circulate the air.

[10][11] George W. Jackson, the contractor who built the tunnel system, received several patents related to building such shafts.

[50] On the grades leading up from the tunnel to the Grant Park disposal station, the Morgan system sold by the Goodman Equipment Mfg.

[54] Temporary Morgan third-rail was installed in the tunnels during installation of the telephone cables on the tunnel ceiling,[7] but after construction was completed, the Morgan system was only used in the context of the grade to the Grant Park disposal station[10][11] and its use ceased with the closure of that disposal station.

[61][62][63][64] Ash and excavation debris removal cars were equipped with the Newman patent dump box[65] with a 3.5 cubic yards (2.7 m3) capacity.

In a typical 10-hour work day, there were 500 to 600 train movements, all conducted under the authority of a telephone-based dispatching system.

[70] The Illinois Tunnel Company built connections to post offices and passenger stations specifically for mail service.

Within six months, it became apparent that the Tunnel Company was having difficulty with timely delivery, and the post office threatened to abrogate its contract.

Chicago's new City building on the corner of Washington and LaSalle had a subbasement 38 feet (11.58 m) below sidewalk level, so the tunnel connection was made by a 10-foot-deep (3.05 m) trench.

The ones that kept burning coal switched to delivery by truck because unloading from the surface was easier, and a complex conveyor system was not required.

[10][11][40] In the early days of tunneling, excavation debris was hauled to the surface through small construction shafts and then to the lakefront by horse and wagon.

[66] The new Cook County Courthouse was among the construction sites that disposed of excavation debris through the tunnel system.

[85] In 1908, further dumping of refuse on the lake front was prohibited, and the Tunnel Company responded by building a new disposal station on the Chicago River.

[86] George W. Jackson, the Tunnel's chief engineer, filed a patent on a scow fitting this description.

[87] Filling on the lakefront began again in 1913, with the construction of a tunnel extension to a new disposal station on the lake shore beyond what was then the south end of Grant Park.

[72] Immense amounts of fill were hauled by tunnel to the lake during construction of Chicago's new main post office adjacent to Union Station in the early 1920s.

[citation needed] This basically left the company in the ash removal business for the last ten years of operation.

At the time, an estimated ten percent of Chicago's loop businesses already used district heating services provided by the Illinois Maintenance Company, formerly part of Insull Utilities Investment Inc.[24]