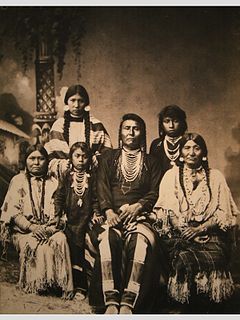

Chief Joseph

Chief Joseph led his band of Nez Perce during the most tumultuous period in their history, when they were forcibly removed by the United States federal government from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley of northeastern Oregon onto a significantly reduced reservation in the Idaho Territory.

A series of violent encounters with white settlers in the spring of 1877 culminated in those Nez Perce who resisted removal, including Joseph's band and an allied band of the Palouse tribe, fleeing the United States in an attempt to reach political asylum alongside the Lakota people, who had sought refuge in Canada under the leadership of Sitting Bull.

In October 1877, after months of fugitive resistance, most of the surviving remnants of Joseph's band were cornered in northern Montana Territory, just 40 miles (64 km) from the Canadian border.

Unable to fight any longer, Chief Joseph surrendered to the Army with the understanding that he and his people would be allowed to return to the reservation in western Idaho.

Government commissioners asked the Nez Perce to accept a new, much smaller reservation of 760,000 acres (3,100 km2) situated around the village of Lapwai in western Idaho Territory, and excluding the Wallowa Valley.

Joseph the Elder demarcated Wallowa land with a series of poles, proclaiming, "Inside this boundary all our people were born.

The non-treaty Nez Perce suffered many injustices at the hands of settlers and prospectors, but out of fear of reprisal from the militarily superior Americans, Joseph never allowed any violence against them, instead making many concessions to them in the hope of securing peace.

A handwritten document mentioned in the Oral History of the Grande Ronde recounts an 1872 experience by Oregon pioneer Henry Young and two friends in search of acreage at Prairie Creek, east of Wallowa Lake.

But in 1877, the government reversed its policy, and Army General Oliver O. Howard threatened to attack if the Wallowa band did not relocate to the Idaho reservation with the other Nez Perce.

Still hoping to avoid further bloodshed, Joseph and other non-treaty Nez Perce leaders began moving people away from Idaho.

McWhorter interviewed and befriended Nez Perce warriors such as Yellow Wolf, who stated, "Our hearts have always been in the valley of the Wallowa".

[15] Robert Forczyk states in his book Nez Perce 1877: The Last Fight that the tipping point of the war was that "Joseph responded that his clan's traditions would not allow him to cede the Wallowa Valley".

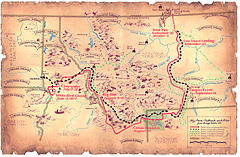

[17] For over three months, the Nez Perce deftly outmaneuvered and battled their pursuers, traveling more than 1,170 miles (1,880 km) across present-day Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana.

[16] General Howard arrived on October 3, leading the opposing cavalry, and was impressed with the skill with which the Nez Perce fought, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines, and field fortifications.

Following a devastating five-day siege during freezing weather, with no food or blankets and the major war leaders dead, Chief Joseph formally surrendered to General Miles on the afternoon of October 5, 1877.

The battle is remembered in popular history by the words attributed to Joseph at the formal surrender: Tell General Howard I know his heart.

[19]The popular legend deflated, however, when the original pencil draft of the report was revealed to show the handwriting of the later poet and lawyer Lieutenant Charles Erskine Scott Wood, who claimed to have taken down the great chief's words on the spot.

Haines supports his argument by citing L. V. McWhorter, who concluded "that Chief Joseph was not a military man at all, that on the battlefield he was without either skill or experience".

Toward the end of the following summer, the surviving Nez Perce were taken by rail to a reservation in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma); they lived there for seven years.

Finally, in 1885, Chief Joseph and his followers were granted permission to return to the Pacific Northwest to settle on the reservation around Kooskia, Idaho.

In his last years, Joseph spoke eloquently against the injustice of United States policy toward his people and held out the hope that America's promise of freedom and equality might one day be fulfilled for Native Americans as well.

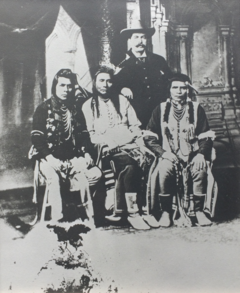

He rode with Buffalo Bill in a parade honoring former President Ulysses Grant in New York City, but he was a topic of conversation for his traditional headdress more than his mission.

In 1903, Chief Joseph visited Seattle, a booming young town, where he stayed in the Lincoln Hotel as guest to Edmond Meany, a history professor at the University of Washington.

[25] An indomitable voice of conscience for the West, still in exile from his homeland, Chief Joseph died on September 21, 1904, according to his doctor, "of a broken heart".

[26][27][28] Meany and Curtis helped Joseph's family bury their chief near the village of Nespelem, Washington,[29] where many of his tribe's members still live.

Swedish country pop group Rednex sampled a part of his famous speech in their 2000 single The Spirit of the Hawk, which became a worldwide hit.

In his 2000 release Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed...And Some Blues, Dan Fogelberg mentioned Chief Joseph in the song "Don't Let That Sun Go Down," which was recorded live in 1994 in Knoxville, TN.