Child development of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

Styles of children’s learning across various indigenous communities in the Americas have been practiced for centuries prior to European colonization and persist today.

[2] Despite extensive anthropological research, efforts made towards studying children’s learning and development in Indigenous communities of the Americas as its own discipline within Developmental Psychology, has remained rudimentary.

However, studies that have been conducted reveal several larger thematic commonalities, which create a paradigm of children’s learning that is fundamentally consistent across differing cultural communities.

With a relatively neutral platform for everyone to be actively engaged, an environment is promoted where learning to blend differing ideas, agendas and pace is necessary and thus, encouraged.

In addition, narratives and dramatizations are often used as a tool to guide learning and development because it helps contextualize information and ideas in the form of remembered or hypothetical scenarios.

Their eagerness to contribute, ability to execute roles, and search for a sense of belonging helps mold them into valued members of both their families and communities alike.

[12] The value placed on “shared work” or help emphasizes how learning and even motivation are related to the way the children participate and contribute to their family and community.

During interactions where children are integrated into family and community contexts, role-switching, a practice in which roles and responsibilities in completing a task are alternated, is common for the less-experienced to learn from the more-experienced.

Mexican-American teachers with indigenous-influenced backgrounds facilitate smooth, back-and-forth coordination when working with students and in these interactions, guidance of children’s attention is not forced.

A teacher will focus more on their own understanding of the task they are teaching, use natural intonation, flow of conversation, and non-rhetorical questions with the children to guide, but not control their learning.

[18] Different learning cues through guidance from the teacher and keen attention from the child are employed to identify when someone is more able to contribute to the larger group or the community.

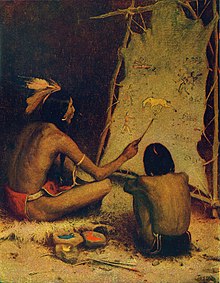

Stories are often employed in order to pass on moral and cultural lessons throughout generations of Indigenous peoples, and are rarely used as a unidirectional transference of knowledge.

Rather, narratives and dramatizations contextualize information and children are encouraged to participate and observe storytelling rituals in order to take part in the knowledge exchange between elder and child.

Because the children are incrementally eased into taking a bigger part in the community, processes, tasks, and activities are adequately completed with no compromise to quality.

Contrasted with patterns of parent-child engagement in Western communities, it is evident that child learning participation and interaction styles are relative socio-cultural constructs.

Factors such as historical context, values, beliefs, and practices must be incorporated into the interpretation of a cultural community and children’s acquisition of knowledge should not be considered universal.