Child labour in Africa

A study published in 2016 "Understanding child labour beyond the standard economic assumption of monetary poverty" illustrates that a broad range of factors – on the demand- and supply-side and at the micro and macro levels – can affect child labour; it argues that structural, geographic, demographic, cultural, seasonal and school-supply factors can also simultaneously influence whether children work or not, questioning thereby the common assumption that monetary poverty is always the most important cause.

[9] In another study, Oryoie, Alwang, and Tideman (2017)[10] show that child labour generally decreases as per capita land holding (as an indicator of a household's wealth in rural areas) increases, but there can be an upward bump in the relationship between child labour and landholding near the middle of the range of land per capita.

In addition to poverty, Lack of resources, together with other factors such as credit constraints, income shocks, school quality, and parental attitudes toward education are all associated with child labour.

This is not unique to Africa; large number of children have worked in agriculture and domestic situations in America, Europe and every other human society, throughout history, prior to 1950s.

Even after retirement from formal work, Africans often revert to the skills they learnt when they were young, for example farming, for a living or enterprise.

Child labor in Africa, as in other parts of the world, was also viewed as a way to instill a sense of responsibility and a way of life in children particularly in rural, subsistence agricultural communities.

In rural Pare people of northern Tanzania, for example, five-year-olds would assist adults in tending crops, nine-year-olds help carry fodder for animals and responsibilities scaled with age.

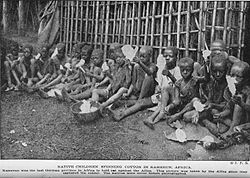

[18][19] The growth of colonial rule in Africa, from 1650 to 1950, by powers such as Britain, France, Belgium, Germany and Netherlands encouraged and continued the practice of child labour.

Colonial administrators preferred Africa's traditional kin-ordered modes of production, that is hiring a household for work not just the adults.

Since that time, the government has adopted a National Action Plan, and in collaboration with Interpol, have since have rescued many children from child trafficking.

[29] In 2008, Bloomberg claimed child labour in copper and cobalt mines of DR Congo that supplied Chinese companies.

[34] Children also work in agriculture and continue to be recruited as child soldiers for Congolese National Army and various rebel groups.

In Ghana 64% of children seek work for financial reasons, making it the leading driver for child labor in the region.

In Urban areas, such as Accra and Ashanti children are often not enrolled in school and are often engaged in artisanal fishing and domestic services.

The informal sectors witnessing the worst form of child labour include sugarcane plantations, pastoral ranches, tea, coffee, miraa (a stimulant plant), rice, sisal, tobacco, tilapia and sardines fishing.

Other economic activities of children in Kenya include scavenging dumpsites, collecting and selling scrap materials, glass and metal, street vending, herding and begging.

Another French based group suggests Madagascar child labour exceeds 2.4 million, with over 540,000 children aged 5–9 working.

About 87% of the child labour is in agriculture, mainly in the production of vanilla, tea, cotton, cocoa, copra (dried meat of coconut), sisal, shrimp harvest and fishing.

Young girls, locally called as petites bonnes (little maids), are sent to work as live in domestic servants, many aged 10 or less.

These petites bonnes come from very poor families, face conditions of involuntary servitude, including long hours without breaks, absence of holidays, physical, verbal and sexual abuse, withheld wages and even restrictions on their movement.

These children survive by selling cigarettes, begging, shining shoes, washing cars and working as porters and packers in ports.

[57] According to the report, despite the Government's moderate advancement in eliminating child labor, children in Tanzania still engage in agricultural and mining activities as indentured labourers.

The informal sectors witnessing the worst form of child labour include cotton plantations, tobacco, fishing, tea, coffee and charcoal.

However, this is witnessed in small artisanal and traditional mines, where the children extract emeralds, amethyst, aquamarines, tourmalines and garnets.

[58] International Labor Organization (ILO) stated that first of all, poverty is the greatest single force driving children into the workplace.

One such project, launched in 2006 is focussed on west African nations of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

It has two main components: the first will support national efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labour, while the second aims at mobilizing sub-regional policy makers and improving sub-regional cooperation for the elimination of the worst forms of child labour among all fifteen member States of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

Funded by the United States Department of Labor and implemented by World Vision, the Academy for Educational Development, and the International Rescue Committee, KURET began in September 2004.

The organization emphasizes a need for a rights-based approach due to the consequences of rapid population growth in Ghana, which results from a lack of health care for the poor.

To eliminate a long-term poverty spiral, the organization focuses on actions which empower communities to reestablishing human rights by reducing child labor in Ghana.