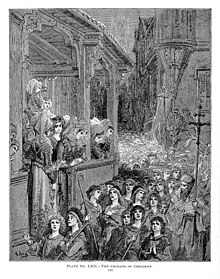

Children's Crusade

The traditional narrative is likely conflated from a mix of historical and mythical events, including the preaching of visions by a French boy and a German boy, an intention to peacefully convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity, bands of children marching to Italy, and children being sold into slavery in Tunis.

A boy begins to preach in either France or Germany, claiming that he had been visited by Jesus, who instructed him to lead a crusade in order to peacefully convert Muslims to Christianity.

In Pisa, two ships directed to Palestine agreed to embark several of the children who, perhaps, managed to reach the Holy Land.

Nicholas did not survive the second attempt across the Alps; back home his father was arrested and hanged under pressure from angry families whose relatives had perished while following the children.

[3] The second movement was led by a twelve-year-old[3] French shepherd boy named Stephen (Étienne) of Cloyes, who said in June that he bore a letter for the king of France from Jesus who was disguised as a poor pilgrim.

[6][4] Large gangs of youths around his age were drawn to him, most of whom claimed to possess special gifts of God and thought themselves miracle workers.

[3] Two French merchants (Hugh the Iron and William of Posqueres) offered to carry any children that were willing to pay a small fee by boat.

It is only in the later non-authoritative narratives that a "children's crusade" is implied by such authors as Vincent of Beauvais, Roger Bacon, Thomas of Cantimpré, Matthew Paris and many others.

At least one source, that of a man simply known as Otto the last puer, was written by an individual who claimed to have participated in the Children's Crusade.

[2] German psychiatrist Justus Hecker (1865) did give an original interpretation of the crusade, but it was a polemic about "diseased religious emotionalism" that has since been discredited.

[9] Adolf Waas (1956) saw the Children's Crusade as a manifestation of chivalric piety and as a protest against the glorification of the holy war.

It was this recognition that undermined all other interpretations,[12] except perhaps that of Norman Cohn (1957) who saw it as a chiliastic movement in which the poor tried to escape the misery of their everyday lives.

[13] In his book Children's Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory (2008), Gary Dickson discusses the growing number of "impossibilist" movements across Western Europe at the time.

Infamous for their shunning of any form of wealth and refusing to join a monastery, they would travel in groups and rely upon small donations or meals from those who listened to their sermons to survive.

This comes in large part from the words "parvuli" or "infantes" found in two accounts of the event from William of Andres and Alberic of Troisfontaines.

The Church then co-opted this classification to a societal coding, with the expression referring to wage workers or labourers who were young and had no inheritance.

[14][18] Further theories by other historians suggest that the fixations on children within the traditional narrative of these events are to corroborate with perceptions of the Crusades during certain periods of time.

First by sources in the Medieval era to portray such religious movements with the innocent and pure nature often affiliated with children in.