2010 Copiapó mining accident

Seventeen days after the accident, a note was found taped to a drill bit pulled back to the surface: "Estamos bien en el refugio los 33" ("We are well in the shelter, the 33 of us").

Three separate drilling rig teams; nearly every Chilean government ministry; the United States' space agency, NASA; and a dozen corporations from around the world cooperated in completing the rescue.

On 13 October 2010, the men were winched to the surface one at a time, in a specially built capsule, as an estimated 5.3 million people watched via video stream worldwide.

According to Javier Castillo, secretary of the trade union that represents San José's miners, the company's management operates "without listening to the voice of the workers when they say that there is danger or risk".

[30] Out-of-date mine shaft maps complicated rescue efforts, and several boreholes drifted off-target[31] due to drilling depth and hard rock.

[38] The trapped miners' emergency shelter had an area of 50 square meters (540 sq ft) with two long benches,[39] but ventilation problems had led them to move out into a tunnel.

[40] Although the emergency supplies stocked in the shelter were intended to last only two or three days, through careful rationing, the men made their meager resources last for two weeks, only running out just before they were discovered.

[42] Shortly after their discovery, 28 of the 33 miners appeared in a 40-minute video recorded using a mini-camera delivered by the government via 1.5-metre-long (5 ft) blue plastic capsules called palomas ("doves", referring to their role as carrier pigeons).

[43] Foreman Luis Urzúa's level-headedness and gentle humor was credited with helping keep the miners under his charge focused on survival during their 70-day underground ordeal.

[39] Out of concern for their morale, rescuers were initially reluctant to tell the miners that in the worst-case scenario, the rescue might take months, with an eventual extraction date close to Christmas.

Teams of miners also patrolled their area to identify and prevent potential rockfalls and pry loose hazardous stones from the ceiling, while others worked to divert the streams of water from the drilling operations.

[61] Chilean Health Minister Jaime Mañalich stated, "The situation is very similar to the one experienced by astronauts who spend months on end in the International Space Station.

[63] After the rescue, Rodrigo Figueroa, chief of the Trauma Stress and Disaster unit of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, said there were serious shortcomings in the censorship of letters to and from miners' relatives above ground and in the monitoring of activities they could undertake, as being underground had suddenly turned them back into "babies."

Small shrines were erected at the foot of each flag and amongst the tents, they placed pictures of the miners, religious icons and statues of the Virgin Mary and patron saints.

"[73] Three large escape boreholes were drilled concurrently using several types of equipment provided by multiple international corporations and based on three different access strategies.

[73][85] The rescue operation was an international effort that involved not only technology, but the cooperation and resources of companies and individuals from around the world, including Latin America, South Africa, Australia, the United States and Canada.

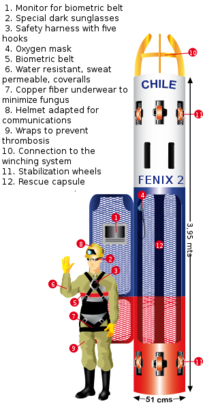

[87][88][89] The steel rescue capsules, dubbed Fénix (English: Phoenix) were constructed by the Chilean shipbuilding company Astilleros y Maestranzas de la Armada (ASMAR) with design input from NASA.

Dubbed Operación San Lorenzo (Operation St. Lawrence) after the patron saint of miners,[68][97][98] a three-hour initial delay ensued while final safety tests were carried out.

[114] This grouping was based on the theory that the first men to exit should be those more skilled and in the best physical condition, as they would be better equipped to escape unaided in the event of a capsule malfunction or shaft collapse.

The final group comprised the most mentally tough, as they had to be able to endure the anxiety of the wait;[115] in the words of Minister Mañalich, "they don't care to stay another 24 hours inside the mine".

[147] Marc Siegel, an associate professor of medicine at the New York University Langone Medical Center, said that lack of sunlight could cause problems with muscles, bones, and other organs.

"[148] Officials considered canceling plans for a Thanksgiving Mass for the men and their families at Camp Hope on 17 October over fears that a premature return to the site could be too stressful.

"[149] In the years after the accident, although initially they enjoyed worldwide fame, gifts of motorcycles, and invitations to Disney World and the Greek Islands, many spiraled, suffering psychologically and financially.

"[150] On Sunday, 17 October 2010, six of the 33 rescued miners attended a multi-denominational memorial Mass led by an evangelical pastor and a Roman Catholic priest at "Campamento Esperanza" (Camp Hope) where anxious relatives had awaited the men's return.

[152] On 24 October 2010, the miners attended a reception hosted by Piñera at the presidential palace in the capital, Santiago, and were awarded medals celebrating Chile's independence bicentennial.

"[161] The Daily Telegraph UK newspaper reported that the miners have hired an accountant to ensure that any income from their new celebrity status is fairly divided, including money from expected book and film deals.

As of December 2010[update], potential locations include Copiapó, the city closest to the accident site, and Talcahuano, 1,300 miles (2,100 km) to the south, where the capsules were built at a Chilean navy workshop.

[166] The Fénix 1 capsule was a featured display at the March 2011 Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada convention in Toronto, Ontario, where Laurence Golborne and the rescue team were honored.

Tobar had exclusive access to the miners and in October 2014 published an official account titled Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free.

"[170] These books include the following: A film titled The 33 based on the events of the disaster is directed by Patricia Riggen and written by Mikko Alanne and Jose Rivera.