Chinese dragon

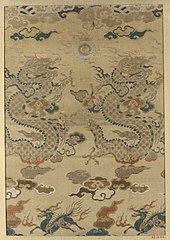

Chinese dragons have many animal-like forms, such as turtles and fish, but are most commonly depicted as snake-like with four legs.

[8] Sometimes Chinese people use the term "Descendants of the Dragon" (龙的传人; 龍的傳人) as a sign of ethnic identity, as part of a trend started in the 1970s when different Asian nationalities were looking for animal symbols as representations.

[10] Dragon-like motifs of a zoomorphic composition in reddish-brown stone have been found at the Chahai site (Liaoning) in the Xinglongwa culture (6200–5400 BC).

Scientific examination of "dragon bones" from the 19th century to the present suggests they most commonly are remains of fossil Cenozoic mammals, such as the extinct horse Hipparion.

From its origins as totems or the stylized depiction of natural creatures, the Chinese dragon evolved to become a mythical animal.

According to legend, the dragon's flight is enabled by something on its head named chimu (Wade-Giles: ch'ih-mu, 尺木, lit.

'foot-long wood/tree'[a]) that resembled the boshan (Wade-Giles: Po-shan, incense burner,[19] i.e. boshanlu or "Hill censer"), without which the dragon cannot fly.

[citation needed] In many other countries, folktales speak of the dragon having all the attributes of the other 11 creatures of the zodiac, this includes the whiskers of the Rat, the face and horns of the Ox, the claws and teeth of the Tiger, the belly of the Rabbit, the body of the Snake, the legs of the Horse, the goatee of the Goat, the wit of the Monkey, the crest of the Rooster, the ears of the Dog, and the snout of the Pig.

[citation needed] According to an art historian John Boardman, depictions of Chinese Dragon and Indian Makara might have been influenced by Cetus in Greek mythology possibly after contact with silk-road images of the Kētos as Chinese dragon appeared more reptilian and shifted head-shape afterwards.

In premodern times, many Chinese villages (especially those close to rivers and seas) had temples dedicated to their local "dragon king".

In times of drought or flooding, it was customary for the local gentry and government officials to lead the community in offering sacrifices and conducting other religious rites to appease the dragon, either to ask for rain or a cessation thereof.

In coastal regions of China, Korea, Vietnam, traditional legends and worshipping of whale gods as the guardians of people on the sea have been referred to Dragon Kings after the arrival of Buddhism.

At the end of his reign, the first legendary ruler, the Yellow Emperor, was said to have been immortalized into a dragon that resembled his emblem, and ascended to Heaven.

A burial site Xishuipo in Puyang which is associated with the Yangshao culture shows a large dragon mosaic made out of clam shells.

The linguist Michael Carr analyzed over 100 ancient dragon names attested in Chinese classic texts.

Dragons were varyingly thought to be able to control and embody various natural elements in their "mythic form" such as "water, air, earth, fire, light, wind, storm, [and] electricity".

Several Ming dynasty texts list what were claimed as the Nine Offspring of the Dragon (龍生九子), and subsequently these feature prominently in popular Chinese stories and writings.

The scholar Xie Zhaozhe [zh] (1567–1624) in his work Wu Za Zu Wuzazu [zh] (c. 1592) gives the following listing, as rendered by M. W. de Visser: A well-known work of the end of the sixteenth century, the Wuzazu 五雜俎, informs us about the nine different young of the dragon, whose shapes are used as ornaments according to their nature.

Further, the same author enumerates nine other kinds of dragons, which are represented as ornaments of different objects or buildings according to their liking prisons, water, the rank smell of newly caught fish or newly killed meat, wind and rain, ornaments, smoke, shutting the mouth (used for adorning key-holes), standing on steep places (placed on roofs), and fire.

[34] The Sheng'an waiji (升庵外集) collection by the poet Yang Shen (1488–1559) gives different 5th and 9th names for the dragon's nine children: the taotie, form of beasts, which loves to eat and is found on food-related wares, and the jiāo tú (椒圖), which looks like a conch or clam, does not like to be disturbed, and is used on the front door or the doorstep.

In addition, there are some sayings including bā xià 𧈢𧏡, Hybrid of reptilia animal and dragon, a creature that likes to drink water, and is typically used on bridge structures.

[5] Phoenixes and five-clawed two-horned dragons may not be used on the robes of officials and other objects such as plates and vessels in the Yuan dynasty.

The three-clawed dragon was used by lower ranks and the general public (widely seen on various Chinese goods in the Ming dynasty).

Improper use of claw number or colors was considered treason, punishable by execution of the offender's entire clan.

[41] In works of art that left the imperial collection, either as gifts or through pilfering by court eunuchs (a long-standing problem), where practicable, one claw was removed from each set, as in several pieces of carved lacquerware,[42] for example the Chinese lacquerware table in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Because nine was considered the number of the emperor, only the most senior officials were allowed to wear nine dragons on their robes—and then only with the robe completely covered with surcoats.

[45] The Azure Dragon is considered to be the primary of the four celestial guardians, the other three being the Vermilion Bird, White Tiger, Black Tortoise.

In many Buddhist countries, the concept of the nāga has been merged with local traditions of great and wise serpents or dragons, as depicted in this stairway image of a multi-headed nāga emerging from the mouth of a Makara in the style of a Chinese dragon at Phra Maha Chedi Chai Mongkol on the premises of Wat Pha Namthip Thep Prasit Vararam in Nong Phok District, Roi Et Province, Thailand.

[citation needed] As a part of traditional folklore, dragons appear in a variety of mythological fiction.

Chinese dragons appear in innumerable media across popular culture today, including but not at all limited to: Japanese anime films and television shows, manga, and in Western political cartoons as a personification of the People's Republic of China.