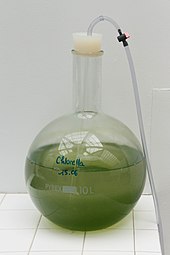

Chlorella

In ideal conditions cells of Chlorella multiply rapidly, requiring only carbon dioxide, water, sunlight, and a small amount of minerals to reproduce.

In 1961, Melvin Calvin of the University of California received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his research on the pathways of carbon dioxide assimilation in plants using Chlorella.

[10] Following global fears of an uncontrollable human population boom during the late 1940s and the early 1950s, Chlorella was seen as a new and promising primary food source and as a possible solution to the then-current world hunger crisis.

Many people during this time thought hunger would be an overwhelming problem and saw Chlorella as a way to end this crisis by providing large amounts of high-quality food for a relatively low cost.

Initial testing by the Stanford Research Institute showed Chlorella (when growing in warm, sunny, shallow conditions) could convert 20% of solar energy into a plant that, when dried, contains 50% protein.

[11] The pilot research performed at Stanford and elsewhere led to immense press from journalists and newspapers, yet did not lead to large-scale algae production.

Algae researchers had even hoped to add a neutralized Chlorella powder to conventional food products, as a way to fortify them with vitamins and minerals.

John Burlew, the editor of the Carnegie Institution of Washington book Algal Culture-from Laboratory to Pilot Plant, stated, "the algae culture may fill a very real need",[12] which Science News Letter turned into "future populations of the world will be kept from starving by the production of improved or educated algae related to the green scum on ponds".

A few years later, the magazine published an article entitled "Tomorrow's Dinner", which stated, "There is no doubt in the mind of scientists that the farms of the future will actually be factories."

Since the growing world food problem of the 1940s was solved by better crop efficiency and other advances in traditional agriculture, Chlorella has not seen the kind of public and scientific interest that it had in the 1940s.

A sophisticated process, and additional cost, was required to harvest the crop and for Chlorella to be a viable food source, its cell walls would have to be pulverized.

[11] Chlorella, too, was found by scientists in the 1960s to be impossible for humans and other animals to digest in its natural state due to the tough cell walls encapsulating the nutrients, which presented further problems for its use in American food production.

[11] In 1965, the Russian CELSS experiment BIOS-3 determined that 8 m2 of exposed Chlorella could remove carbon dioxide and replace oxygen within the sealed environment for a single human.

Chlorella protothecoides accelerated the detoxification of rats poisoned with chlordecone, a persistent insecticide, decreasing the half-life of the toxin from 40 to 19 days.

[18] The ingested algae passed through the gastrointestinal tract unharmed, interrupted the enteric recirculation of the persistent insecticide, and subsequently eliminated the bound chlordecone with the feces.

A 2002 study showed that Chlorella cell walls contain lipopolysaccharides, endotoxins found in Gram-negative bacteria that affect the immune system and may cause inflammation.