Seals in the Sinosphere

In Japan, seals, referred to as inkan (印鑑) or hanko (判子), have historically been used to identify individuals involved in government and trading from ancient times.

The Japanese emperors, shōguns, and samurai had their personal seals pressed onto edicts and other public documents to show authenticity and authority.

[4][5] The earliest known examples of seals in ancient China date to the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC) and were discovered at archaeological sites at Anyang.

[4][5] But when Emperor Zhongzong was resumed to the throne of the Tang dynasty in the year 705, he changed the name for imperial seals back to xǐ.

[7][8] The government of the Republic of China in Taiwan has continued to use traditional square seals of up to about 13 centimetres, known by a variety of names depending on the user's hierarchy.

Government seals in the People's Republic of China today are usually circular in shape, and have a five-pointed star in the centre of the circle.

In Imperial China it was considered to be customary for collectors and connoisseurs of art to affix the print of their seals on the surface of a scroll of painting or calligraphy.

[4] As such, many famous paintings from the Forbidden City in Beijing tend to have the imperial seals for art appraisal and appreciation of generations of subsequent emperors on them.

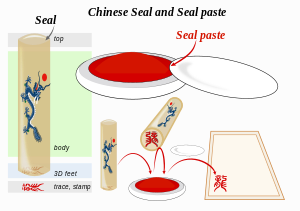

For silk based paste, the user applies pressure, often with a specially made soft, flat surface beneath the paper.

), this practice does not devalue the painting but could possibly enhance it by giving it further provenance, especially if it is a seal of a famous or celebrated individual who possessed the work at some point.

Some people carve their own seals using soapstone and fine knives, which are widely available; this is cheaper than paying a professional for expertise, craft and material.

Their handles are often ornately carved with friezes of mythical beasts or hand-carved hakubun inscriptions that might be quotes from literature, names and dates, or original poetry.

For example, in Hiroshima, a jitsuin is expected to be roughly 1⁄2 to 1 inch (1.3 to 2.5 cm), usually square or (rarely) rectangular but never round, irregular, or oval.

The top and sides (handle) of the seal may be decorated in any fashion from completely undecorated to historical animal motifs, dates, names, and inscriptions.

People desirous of opening a new chapter in their lives—say, following a divorce, death of a spouse, a long streak of bad luck, or a change in career—will often have a new jitsuin made.

An intō is a flat-bladed pencil-sized chisel, usually round or octagonal in cross-section and sometimes wrapped in string to give a better grip.

They are usually stored in thumb-sized rectangular boxes made of cardboard covered with embroidered green fabric outside and red silk or red velvet inside, held closed by a white plastic or deerhorn splinter tied to the lid and passed through a fabric loop attached to the lower half of the box.

A person's savings account passbook contains an original impression of the ginkō-in alongside a bank employee's seal.

Mitome-in are commonly stored in low-security, high-utility places such as office desk drawers and in the anteroom (genkan) of a residence.

A man's is usually slightly larger than a woman's, and a junior employee's is always smaller than his bosses' and his senior co-workers', in keeping with office social hierarchy.

Mitome-in and lesser seals are usually stored in inexpensive plastic cases, sometimes with small supplies of red paste or a stamp pad included.

Most Japanese also have a less formal seal used to sign personal letters or initial changes in documents; this is referred to by the broadly generic term hanko.

Traditionally, inkan and hanko are engraved on the end of a finger-length stick of stone, wood, bone, or ivory, with a diameter between 25 and 75 millimetres (0.98 and 2.95 in).

[15][16] During 2020, the Japanese government has been attempting to discourage the use of seals, because the practice requires generation of paper documents that interfere with electronic record-keeping and slow digital communications.

Japanese prime minister Yoshihide Suga had set the digitalization of the bureaucracy and ultimately of Japan's entire society as a key priority.

In the case of State Seals in monarchic Korea, there were two types in use: Gugin (국인, 國印) which was conferred by the Emperor of China to Korean kings, with the intent of keeping relations between two countries as brothers (Sadae).

Others, generally called eobo (어보, 御寶) or eosae (어새, 御璽), are used in foreign communications with countries other than China, and for domestic uses.

[citation needed] With the declaration of establishment of Republic of Korea in 1948, its government created a new State Seal, guksae (국새, 國璽) and it is used in promulgation of constitution, designation of cabinet members and ambassadors, conference of national orders and important diplomatic documents.

While it was scheduled to be completely replaced by an electronic certification system in 2013 in order to counter fraud, as of 2021[update] ingam still remains an official means of verification for binding legal agreement and identification.

Seals of Joseon-period calligraphist and natural historian Kim Jung-hee (aka Wandang or Chusa) are considered to be antiques.