Chorale

The cantata genre, originally consisting only of recitatives and arias, was introduced into Lutheran church services in the early 18th century.

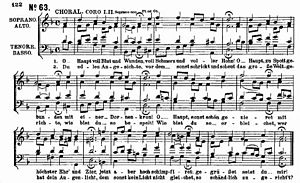

Composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach and Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel often placed these chorales as the concluding movement of their church compositions.

In German, the word Choral may as well refer to Protestant congregational singing as to other forms of vocal (church) music, including Gregorian chant.

[2] Johann Pachelbel's Erster Theil etlicher Choräle, a set of organ chorales, was published in the last decade of the 17th century.

Johann Sebastian Bach's earliest extant compositions, works for organ which he possibly wrote before his fifteenth birthday, include the chorales BWV 700, 724, 1091, 1094, 1097, 1112, 1113 and 1119.

[3] In the early 18th century Erdmann Neumeister introduced the cantata format, originally consisting exclusively of recitatives and arias, in Lutheran liturgical music.

The chorale cantata, called per omnes versus (through all verses) when its libretto was an entire unmodified Lutheran hymn, was also a format modernised from earlier types.

These closing chorales almost always conformed to these formal characteristics: Around 400 of such settings by Bach are known, with the colla parte instrumentation surviving for more than half of them.

Larger-scale compositions, such as Passions and oratorios, often contain multiple four-part chorale settings which in part define the composition's structure: for instance in Bach's St John and St Matthew Passions they often close units (scenes) before a next part of the narrative follows, and in the Wer ist der, so von Edom kömmt Passion pasticcio the narrative is carried by interspersed four-part chorale settings of nearly all stanzas of the "Christus, der uns selig macht" hymn.

[7][8] Felix Mendelssohn, champion of the 19th-century Bach Revival, included a chorale ("Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott") in the finale of his Reformation Symphony (1830).

[7] His first oratorio, Paulus, which premièred in 1836, featured chorales such as "Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr" and "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme".

[7] Lutheran hymns also appear in the composer's chorale cantatas, some of his organ compositions, and the sketches of his unfinished Christus oratorio.

Joachim Raff included Luther's "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" in his Overture Op.

[7] In 1881 Sergei Taneyev described chorale harmonisations, such as those ending Bach's cantatas, rather as a necessary evil: inartistic, but unavoidable, even in Russian church music.

[15] From the 1880s Ferruccio Busoni was adopting chorales in his instrumental compositions, often adapted from or inspired by models by Johann Sebastian Bach: for example BV 186 (c. 1881), an introduction and fugue on "Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen", No.

[17] Shortly after Mahler had completed the symphony, his wife Alma reproached him to have included a dreary church-like chorale in the work.

[25][26][27] Stand-alone orchestral chorales were adapted from works by Johann Sebastian Bach: for instance Leopold Stokowski orchestrated, among other similar pieces, the sacred song BWV 478 and the fourth movement of the cantata BWV 4 as chorales Komm, süsser Tod (recorded 1933) and Jesus Christus, Gottes Sohn (recorded 1937) respectively.