Choristodera

[3][4] A year later, in 1877, Simoedosaurus was described by Paul Gervais from Upper Paleocene deposits at Cernay, near Rheims, France.

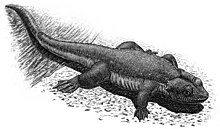

Other choristoderes are referred to collectively as "non-neochoristoderes", which are mostly small lizard-like forms, though Shokawa, Khurendukhosaurus and Hyphalosaurus possess long plesiosaur like necks.

The feet display evidence of webbing, and the tail probably had additional tissue at the top and bottom, allowing it to be used as a fin to propel Hyphalosaurus through the water.

[16] The Menat specimen of Lazarussuchus preserves some remnants of soft tissue, but no scales, which shows that the hindfoot (pes) was not webbed, and a dark stained region with a crenellated edge is present above the caudal vertebrae of the tail, suggestive of a crest similar to those found in some living reptiles, like the tuatara, lizards and crocodiles.

They appear to have been almost exclusively found in warm temperate climates, with the range of neochoristoderes extending to the high Canadian Arctic during the Coniacian-Santonian stages of the Late Cretaceous (~89-83 Million years ago), a time of extreme warmth.

[22] A possible explanation for this is that Hyphalosaurus was ovoviviparous, with the thin-shelled eggs hatching immediately after they were laid, presumably on land,[23] though it has also been suggested that the species employed both viviparous and oviparous reproductive modes.

[24] A skeleton of Philydrosaurus has been found with associated post-hatchling stage juveniles, suggesting that they engaged in post-hatching parental care.

[25] Tracks attributed to neochoristoderans dubbed Champsosaurichnus parfeti have also been reported from the Late Cretaceous Laramie Formation of the United States, though only two prints are present and it is not possible to distinguish between a manus (forefoot) or pes (hindfoot).

[26] Historically, the internal phylogenetics of Choristodera were unclear, with the neochoristoderes being recovered as a well-supported clade, but the relationships of the "non-neochoristoderes" being poorly resolved.

[7] However, during the 2010s, the "non-neochoristoderes" from the Early Cretaceous of Asia (with the exception of Heishanosaurus) alongside Lazarussuchus from the Cenozoic of Europe were recovered (with weak support) as belonging to a monophyletic clade, which were informally named the "Allochoristoderes" by Dong and colleagues in 2020, characterised by the shared trait of completely closed lower temporal fenestrae, with Cteniogenys from the Middle-Late Jurassic of Europe and North America being consistently recovered as the basalmost choristodere.

[27] The finding of more complete material of the previously fragmentary Khurendukhosaurus shows that it also has a long neck, and it has also been recovered as part of the clade.

Hyphalosaurus lingyuanensis Shokawa ikoi Choristoderes are universally agreed to be members of Neodiapsida, but their exact placement in the clade is uncertain, due to their mix of primitive and derived features, and a long ghost lineage (absence of a fossil record) after their split from other reptiles.

Alfred Romer in publications in 1956 and 1968 placed Choristodera within the paraphyletic or polyphyletic grouping of "Eosuchia", describing them, as "an offshoot of the basic eosuchian stock", a classification which was widely accepted.

[20] Choristoderes must have diverged from all other known reptile groups prior to the end of the Permian period, over 250 million years ago, based on their primitive phylogenetic position.

[5] In 2015, Rainer R. Schoch reported a new small (~ 20 cm long) diapsid from the Middle Triassic (Ladinian) Lower Keuper of Southern Germany, known from both cranial and postcranial material, which he claimed represented the oldest known choristodere.

[31] Pachystropheus from the Late Triassic (Rhaetian) of Britain was historically suggested to be a choristodere,[32] but was later demonstrated to be a member of the marine reptile group Thalattosauria.

[36] Choristoderes underwent a major evolutionary radiation in Asia during the Early Cretaceous, which represents the high point of choristoderan diversity, including the first records of the gharial-like Neochoristodera, which appear to have evolved in the regional absence of aquatic neosuchian crocodyliformes.

[40] Vertebrae from the Cenomanian of Germany[41] and the Campanian aged Grünbach Formation of Austria[42] indicate the presence of choristoderes in Europe during this time period.

[43] Fragmentary remains found in the Campanian aged Oldman and Dinosaur Park formations in Alberta, Canada, also possibly suggest the presence of small bodied "non-neochoristoderes" in North America during the Late Cretaceous.

[5] Small bodied "non-neochoristoderes", which are absent from the fossil record after the Early Cretaceous (except for possible North American remains), reappear in the form of the lizard-like Lazarussuchus from the late Paleocene of France.