Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection

This allowed the artist to extend his stay in Italy and provided an important foundation for his magnum opus, the canvas The Appearance of Christ Before the People, which Ivanov worked on between 1837 and 1857.

[8][9] The artist and critic Alexandre Benois wrote that the painting Christ's Appearance to the Magdalene showed "all of [Ivanov's] skill in nudity and drapery."

At the same time, according to Benois, in the image of the Magdalene one can see "something that shows what understanding of tragedy Ivanov had already reached, what kind of heart reader he had become, how deeply he could feel, to the point of tears, the tender story of the Gospel".

[10] The art historian Mikhail Alpatov noted that the canvas was "a typical work of academic classicism", yet the artist simultaneously achieved "a grandeur that the academicians did not know".

Nonetheless, the artist initially elected to attempt a more simple, two-figure composition, commencing work on the painting Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene in early 1834.

[8][14][15] In a letter to Count Vasily Musin-Pushkin-Bruce dated 28 February 1834, Ivanov reported: Having never tried myself in the production of more, I have now undertaken to write a picture in two figures, in natural size, representing “Jesus in the vertograd”,[Note 1] which is already underpainted.

In the drawings of this period, Ivanov "pays particular attention to the development of the plasticity of descending draperies, achieving the impression of their weight and shimmering fabric.

"[21] Later, the artist noted: "Careful consideration of the Venetian school, and especially copying Titian, helped me a lot to finish the above-mentioned painting 'Jesus, Revealing Himself to the Magdalene'.

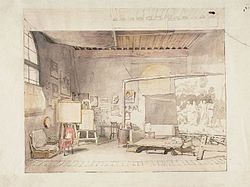

[22][23] In a letter to the Society for the Encouragement of Artists committee dated 27 November 1834, Ivanov reported that he was still working on the painting Jesus, Revealing Himself to the Magdalene after the Resurrection, "three and a half arshin high, five long,"[19] and asked for his pension to be continued: "But, prompted by a lively zeal to prove to the most honourable Society my strength, and to justify myself before it - by the deed itself, I would pray him unceasingly to prolong my pension, promising to send in a short time my painting: ‘Jesus, Revealing Himself to the Magdalene’'"[24] The painting, entitled Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene, was completed in December 1835 and exhibited in the artist's studio.

"[28] In a letter to the committee of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists dated 28 December 1835, Alexander Ivanov expressed gratitude for the "generous patronage with a double production of pension" and wrote "Now, having finished my painting “The Saviour before the Magdalene in Vertograd”, I hurry to present it to the eyes and the court of my patrons.

It was displayed alongside works by Russian painters Orest Kiprensky and Mikhail Lebedev, as well as German artists August Riedel and Franz Ludwig Catel.

His father wrote to him reassuring him that his concerns about the frame and other details were unwarranted, noting that such a painting "uses its own power, makes a strong impression on the soul of the viewer by the feelings depicted in it."

"[34] On 24 September (6 October) 1836, the Imperial Academy of Arts bestowed upon Ivanov the title of Academician in recognition of his painting Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection.

[1] Following the inauguration of the museum in 1898, the painting Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection was displayed at the Mikhailovsky Palace, situated in the same room as the works The Last Day of Pompeii and Siege of Pskov by Karl Bryullov, The Brazen Serpent and Death of Camilla, Sister of Horace by Fyodor Bruni, Christian Martyrs in the Colosseum by Konstantin Flavitsky, Last Supper by Nikolai Ge, and two or three other paintings by Ivan Aivazovsky.

[39] Alexander Ivanov selected the park of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli as the setting for his painting, a location situated in proximity to Rome.

[32] The State Tretyakov Gallery houses several drawings of Christ's head by Ivanov, painted from from various points of view and based on a Thorvaldsen sculpture that the artist worked on during the 1820s and 1830s.

The artist himself noted: "It is not easy to paint a truly colourful white dress that covers most of the figure in its natural size, as my Christ does; the great masters themselves seem to have avoided it.

To evoke this emotional state in the sitter, Ivanov prompted her to recall a sad memory and then made her laugh, inducing tears with a bulb.

She was so kind that, remembering all her troubles and crushing to pieces in front of his face the strongest bow, cried, and at the same minute I made her happy and laughed so that full of tears of her eyes with a smile on her lips gave me a perfect concept of Magdalene, who saw Jesus.

"[52][15] The State Russian Museum holds a sketch of the same name for the painting Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection (canvas, oil, 29 × 37 cm, circa 1833, Inventory No.

Zh-3857), which was previously in the possession of Koritsky, assistant curator of the Imperial Hermitage Picture Gallery, and subsequently to the artist and collector Mikhail Botkin.

[6] Mary Magdalene's face is not visible in the sketch; she has fallen down before Christ, and behind her is an angel seated on a stone slab at the entrance to the tomb.

This resulted in the creation of the sketch Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene at the Resurrection (brown paper, watercolour, whitewash, Italian pencil, 26.3 × 40 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery, Inventory No.

)[63][64][65] In comparison to the 1835 painting, the subsequent sketch evinces a greater sense of impetus and movement in the figures of Christ and Mary Magdalene: "this impression is greatly aided by the character of the architectural space; huge steps going deep into the depths, and the edge of the balustrade crossing the composition.

In Benois's words, "the Torvaldsen Christ, pacing in a frozen theatrical pose, the desiccated, precisely engraved landscape, the timid painting, the enormous labour spent on minor things, like writing out folds, - these are the things that, firstly, first of all, what catches one's eye, and it is only by looking closely that one sees something in Magdalene's head that shows to what understanding of the tragic Ivanov had already reached at that time, what a heartbreaker he had become, how deeply he was able to feel to the point of tears the heart-warming story of the Gospel.

"[10] Art historian Nina Dmitrieva, in her work "Biblical Sketches by Alexander Ivanov", also noted that "in the expression of Magdalene's face, who saw alive the one she thought dead, in her smile through her tears there was a theme of joyful shock, glittering hope, dominating in the psychological solution of the conceived big picture".

Mashkovtsev noted that the painting Christ's Appearance to Mary Magdalene not only satisfied the artist's desire "to show his concept of nudity and draperies", but also contained "something much more.

"[17] Nevertheless, according to Mashkovtsev, the canvas "in its general structure is still a picture of a purely classicist order": generally similar in its composition to Ivanov's academic work Priam asks Achilles to return Hector's body (1824, State Tretyakov Gallery), this later work reveals noble emotions even more clearly, in it "the staging of the figures and the folds of the robes are even more majestic.

Nevertheless, in Alpatov's opinion, Ivanov managed to achieve "a grandeur that the academicians had never known", and "the very juxtaposition of the figures of Christ and Mary Magdalene falling to her knees is the artist's good fortune.