Christian interpretations of Virgil's Eclogue 4

During late antiquity and the Middle Ages, a desire emerged to view Virgil as a virtuous pagan, and as such the early Christian theologian Lactantius, and St. Augustine—to varying degrees—reinterpreted the poem to be about the birth of Jesus Christ.

Modern scholars, such as Robin Nisbet, tend to eschew this interpretation, arguing that seemingly Judeo-Christian elements of the poem can be explained through means other than divine prophecy.

[8] According to Classicist Domenico Comparetti, in the early Christian era, "A certain theological doctrine, supported by various passages of [Judeo-Christian] scripture, induced men to look for prophets of Christ among the Gentiles".

[12] In a chapter of his book, Divinae Institutiones (The Divine Institutes), entitled "Of the Renewed World", Lactantius quotes the Eclogue and argues that it refers to Jesus's awaited return at the end of the millennium.

He further claims that "the poet [i.e. Virgil] foretold [the future coming Christ] according to the verses of the Cumaean Sibyl" (that is, the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae).

St. Jerome, an early Church Father now remembered best for translating the Bible into Latin, specifically wrote that Virgil could not have been a Christian prophet because he never had the chance to accept Christ.

[10][19][24] But regardless of his exact feelings, the classicist Ella Bourne notes that the mere fact Jerome responded to the belief is a testament to its pervasiveness and popularity during that time.

"[25] According to legend, Donatus, a bishop of Fiesole in the ninth century, quoted the seventh line of the poem as part of a confession of his faith prior to his death.

[29] Around this time, Eclogue 4 and Virgil's supposed prophetic nature had saturated the Christian world; references to the poem are made by Abelard, the Bohemian historian Cosmos, and Pope Innocent III in a sermon.

The Gesta Romanorum, a Latin collection of anecdotes and tales that was probably compiled about the end of the 13th century or the beginning of the 14th, confirms that the eclogue was pervasively associated with Christianity.

[30] Virgil eventually became a fixture of Medieval ecclesiastic art, appearing in churches, chapels, and even cathedrals, sometimes depicted holding a scroll with a select passage from the Fourth Eclogue on it.

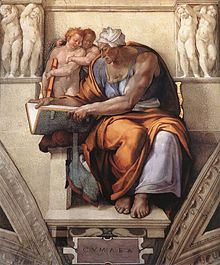

"[32] Barolsky also points out that Michelangelo painted the Sibyl in close proximity to the prophet Isaiah; thus, the painter drew a visual comparison between the similar nature of their prophecies.

The story claims that the trio were alarmed by the calm manner in which their Christian victims died, and so they turned to literature and chanced upon Eclogue 4, which eventually caused their conversions and martyrdom.

[36] In the mid-19th century, Oxford scholar John Keble claimed: Taceo si quid divinius ac sanctius (quod credo equidem) adhaeret istis auguriis ("I am silent about whether something more divine and sacred—which is what I, in fact, believe—clings to these prophecies").