Christian mysticism

[14] Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of religious experience further back to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite.

It also fails to distinguish between episodic experience, and mysticism as a process that is embedded in a total religious matrix of liturgy, scripture, worship, virtues, theology, rituals and practices.

Mysticism thus becomes seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than seeking to transform the world, serve to accommodate the individual to the status quo through the alleviation of anxiety and stress.

[22] Jewish spirituality in the period before Jesus was highly corporate and public, based mostly on the worship services of the synagogues, which included the reading and interpretation of the Hebrew Scriptures and the recitation of prayers, and on the major festivals.

[41][42] Purity of heart was especially important given perceptions of martyrdom, which many writers discussed in theological terms, seeing it not as an evil but as an opportunity to truly die for the sake of God—the ultimate example of ascetic practice.

Clement was an early Christian humanist who argued that reason is the most important aspect of human existence and that gnosis (not something we can attain by ourselves, but the gift of Christ) helps us find the spiritual realities that are hidden behind the natural world and within the scriptures.

Philo also taught the need to bring together the contemplative focus of the Stoics and Essenes with the active lives of virtue and community worship found in Platonism and the Therapeutae.

Using terms reminiscent of the Platonists, Philo described the intellectual component of faith as a sort of spiritual ecstasy in which our nous (mind) is suspended and God's spirit takes its place.

Monasticism, also known as anchoritism (meaning "to withdraw") was seen as an alternative to martyrdom, and was less about escaping the world than about fighting demons (who were thought to live in the desert) and about gaining liberation from our bodily passions in order to be open to the word of God.

[note 3] The Brill Dictionary of Gregory of Nyssa remarks that contemplation in Gregory is described as a "loving contemplation",[59] and, according to Thomas Keating, the Greek Fathers of the Church, in taking over from the Neoplatonists the word theoria, attached to it the idea expressed by the Hebrew word da'ath, which, though usually translated as "knowledge", is a much stronger term, since it indicates the experiential knowledge that comes with love and that involves the whole person, not merely the mind.

[60] Among the Greek Fathers, Christian theoria was not contemplation of Platonic Ideas nor of the astronomical heavens of Pontic Heraclitus, but "studying the Scriptures", with an emphasis on the spiritual sense.

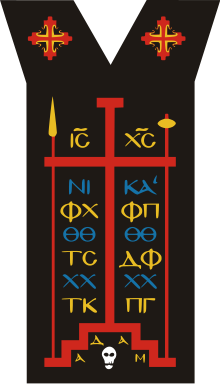

[note 6] Following Christ's instruction to "go into your room or closet and shut the door and pray to your father who is in secret" (Matthew 6:6), the hesychast withdraws into solitude in order that he or she may enter into a deeper state of contemplative stillness.

[note 8] An exercise long used among Christians for acquiring contemplation, one that is "available to everyone, whether he be of the clergy or of any secular occupation",[85] is that of focusing the mind by constant repetition of a phrase or word.

[94] The Jesus Prayer, which, for the early Fathers, was just a training for repose,[95] the later Byzantines developed into hesychasm, a spiritual practice of its own, attaching to it technical requirements and various stipulations that became a matter of serious theological controversy.

[106] A nous in a state of ecstasy or ekstasis, called the eighth day, is not internal or external to the world, outside of time and space; it experiences the infinite and limitless God.

St. Teresa answers: 'Contemplative [sic][note 16] prayer [oración mental] in my opinion is nothing else than a close sharing between friends; it means taking time frequently to be alone with him who we know loves us.'

[122]In the mystical experience of Teresa of Avila, infused or higher contemplation, also called intuitive, passive or extraordinary, is a supernatural gift by which a person's mind will become totally centered on God.

[62] Under this influence of God, which assumes the free cooperation of the human will, the intellect receives special insights into things of the spirit, and the affections are extraordinarily animated with divine love.

John Baptist Scaramelli, reacting in the 17th century against quietism, taught that asceticism and mysticism are two distinct paths to perfection, the former being the normal, ordinary end of the Christian life, and the latter something extraordinary and very rare.

[127] According to Charles G. Herbermann, in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1908), Teresa of Avila described four degrees or stages of mystical union: The first three are weak, medium, and the energetic states of the same grace.

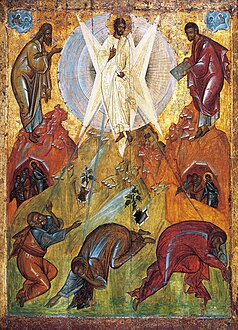

Theoria is the main aim of hesychasm, which has its roots in the contemplative practices taught by Evagrius Ponticus (345–399), John Climacus (6th–7th century), Maximus the Confessor (c. 580–662), and Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022).

The Late Middle Ages saw the clash between the Dominican and Franciscan schools of thought, which was also a conflict between two different mystical theologies: on the one hand that of Dominic de Guzmán and on the other that of Francis of Assisi, Anthony of Padua, Bonaventure, Jacopone da Todi, Angela of Foligno.

Contemporary Protestants saw in the fate of Molinos nothing more than a persecution by the Jesuits of a wise and enlightened man, who had dared to withstand the petty ceremonialism of the Italian piety of the day.

As part of the Protestant Reformation, theologians turned away from the traditions developed in the Middle Ages and returned to what they consider to be biblical and early Christian practices.

[173] However, Quakers, Anglicans, Methodists, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Local Churches, Pentecostals, Adventists, and Charismatics have in various ways remained open to the idea of mystical experiences.

Browne's highly original and dense symbolism frequently involves scientific, medical, or optical imagery to illustrate a religious or spiritual truth, often to striking effect, notably in Religio Medici, but also in his posthumous advisory Christian Morals.

[176] Browne's latitudinarian Anglicanism, hermetic inclinations, and Montaigne-like self-analysis on the enigmas, idiosyncrasies, and devoutness of his own personality and soul, along with his observations upon the relationship between science and faith, are on display in Religio Medici.

His spiritual testament and psychological self-portrait thematically structured upon the Christian virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity, also reveal him as "one of the immortal spirits waiting to introduce the reader to his own unique and intense experience of reality".

[citation needed] Similarly, well-versed in the mystic tradition was the German Johann Arndt, who, along with the English Puritans, influenced such continental Pietists as Philipp Jakob Spener, Gottfried Arnold, Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf of the Moravians, and the hymnodist Gerhard Tersteegen.

Arndt, whose book True Christianity was popular among Protestants, Catholics and Anglicans alike, combined influences from Bernard of Clairvaux, John Tauler and the Devotio Moderna into a spirituality that focused its attention away from the theological squabbles of contemporary Lutheranism and onto the development of the new life in the heart and mind of the believer.