Christian views on magic

At the very least, older biblical prohibitions included those against 'sorcery' to obtain something unnaturally; 'necromancy' as the practice of magic or divination through demons or the dead, and any forms of malevolent 'bewitchery'.

Towards the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period (post-Reformation), belief in witchcraft became more popular and witches were seen as directly in league with the Devil.

This marked the beginning of a period of witch hunts among early Protestants which lasted about 200 years, and in some countries, particularly in North-Western Europe, tens of thousands of people were accused of witchcraft and sentenced to death.

[6] Inquisitorial courts only became systematically involved in the witch-hunt during the 15th century: in the case of the Madonna Oriente, the Inquisition of Milan was not sure what to do with two women who in 1384 and in 1390 confessed to have participated in a type of white magic.

For example, in 1610 as the result of a witch-hunting craze the Suprema (the ruling council of the Spanish Inquisition) gave everybody an Edict of Grace (during which confessing witches were not to be punished) and put the only dissenting inquisitor, Alonso de Salazar Frías, in charge of the subsequent investigation.

Both bourgeoisie and nobility of that era showed great fascination with these arts, which exerted an exotic charm by their ascription to Arabic, Jewish, Romani, and Egyptian sources.

There was great uncertainty in distinguishing practices of vain superstition, blasphemous occultism, and perfectly sound scholarly knowledge or pious ritual.

[16] Marsilio Ficino advocated the existence of spiritual beings and spirits in general, though many such theories ran counter to the ideas of the later Age of Enlightenment, and were treated with hostility by the Roman Catholic Church.

The preface to the Polygraphia establishes the everyday practicability of Trithemian cryptography as a "secular consequent of the ability of a soul specially empowered by God to reach, by magical means, from earth to Heaven".

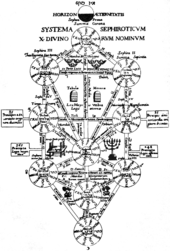

[21] Giovanni Pico della Mirandola promoted a syncretic worldview combining Platonism, Neoplatonism, Aristotelianism, Hermeticism, and Kabbalah.

[20] Pico's Hermetic syncretism was further developed by Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit priest, hermeticist, and polymath, who wrote extensively on the subject in 1652, bringing further elements such as Orphism and Egyptian mythology to the mix.

[22] Lutheran Bishop James Heiser recently evaluated the writings of Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola as an attempted "Hermetic Reformation".

[26] His goal was to help bring forth a unified world religion through the healing of the breach of the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches and the recapture of the pure theology of the ancients.

It was at this time, however, that Western Christianity began expanding to parts of Africa and Asia where premodern worldviews still held sway, and where belief in the power of witches and sorcerers to harm was, if anything, stronger than it had been in Northern Europe.

[32] Among Christian organizations, the NAR is especially aggressive in spiritual warfare efforts to counter alleged acts of witchcraft; the NAR's globally distributed Transformations documentaries by filmmaker George Otis Jr. show charismatic Christians creating mini-utopias by using spiritual mapping to locate and drive off territorial spirits and by banishing accused witches.

[33][34] During the 2008 United States presidential election, footage surfaced from a 2005 church ceremony in which an NAR apostle, Kenyan bishop Thomas Muthee, laid hands on Sarah Palin and called upon God to protect her from "every form of witchcraft".

In the first book in The Chronicles of Narnia, The Magician's Nephew, Lewis specifically explains that magic is a power readily available in some other worlds, less so on Earth.

The Empress Jadis (later, the White Witch) was tempted to use magic for selfish reasons to retain control of her world Charn, which ultimately led to the destruction of life there.