Christianity in Ethiopia

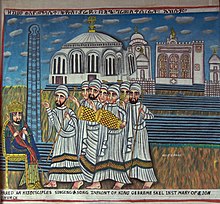

[3] Christianity in Ethiopia dates back to the ancient Kingdom of Aksum, when the King Ezana first adopted the faith in the 4th century AD.

After being shipwrecked and captured at an early age, Frumentius was carried to Aksum, where he was treated well with his companion Edesius.

At the time, there was a small population of West Asian Christians living in Aksum who sought refuge from Roman persecution.

By 331 AD, Frumentius returned to Ethiopia, he was welcomed with open arms by the rulers who were at the time 'not' Christian.

Ten years later, through the support of the kings, the majority of the kingdom was converted and Christianity was declared the official state religion.

The efforts of these Eastern Rite Syriac missionaries from Assyria (Mesopotamia and south east Anatolia), Asia Minor and Aramea (Syria) facilitated the Church’s expansion deep into the interior and caused friction with the traditions of the local people.

These translations were vital to the spread of Christianity, no longer a religion for the small percentage of Ethiopians who could read Greek or Aramaic/Syriac, throughout Ethiopia.

Newly trained Ethiopian ministers opened their own schools in their parishes and offered to educate members of their congregations.

In the late 16th century Christianity spread among petty kingdoms in Ethiopia's west, like Ennarea, Kaffa or Garo.

There is little evidence about the activities of the daily life of the early Aksumite Church, but it is clear that the essential doctrinal and liturgical traditions were established in the first four centuries of its creation.

The strength of these traditions was the main driving force behind the Church’s survival despite its distance from its patriarch in Alexandria.

In response, he sent Makeda home but told her to send their son back to Jerusalem when he came of age to be taught Jewish lore and law.

Furthermore, Siyon's victory caused the frontier of Christian power in Africa to expand past the Awash Valley.

These monks were often killed or injured by the conquered people, but, through hard work, faith, and promises that local elites could keep their positions through conversion, the new territories were converted to Christianity.

The spread of Ewostathianism alarmed the Ethiopian establishment who still considered them to be dangerous due to their refusal to follow state authorities.

This growth was noticed by Dawit's successor, Emperor Zara Yakob (r. 1434-1468) who realized that the energy of the Sabbatarians could be useful in reinvigorating the church and promoting national unity.

Next, Yakob traveled to Aksum for his coronation, remaining there until 1439 and reconciling with the Sabbatarians, who agreed to pay feudal dues to the emperor.

[21] In 1441 some Ethiopian monks traveled from Jerusalem to attend the Council in Florence which discussed possible union between the Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches.