Christianity in the 17th century

The Tsardom of Russia, where Orthodox Christianity was the established religion, expanded eastwards into Siberia and Central Asia, regions of Islamic and shamanistic beliefs, and also southwest into Ukraine, where the Uniate Eastern Catholic Churches arose.

Hagiography became more critical with the Bollandists, and ecclesiastical history became thoroughly developed and debated, with Catholic scholars such as Baronius and Jean Mabillon, and Protestants such as David Blondel laying down the lines of scholarship.

At the beginning of the century James I of England opposed the papal deposing power in a series of controversial works,[2] and the assassination of Henry IV of France caused an intense focus on the theological doctrines concerned with tyrannicide.

[3] Both Henry and James, in different ways, pursued a peaceful policy of religious conciliation, aimed at eventually healing the breach caused by the Protestant Reformation.

While progress along these lines seemed more possible during the Twelve Years' Truce, conflicts after 1620 changed the picture; and the situation of Western and Central Europe after the Peace of Westphalia left a more stable but entrenched polarisation of Protestant and Catholic territorial states, with religious minorities.

By the end of the 17th century, the Dictionnaire Historique et Critique by Pierre Bayle represented the current debates in the Republic of Letters, a largely secular network of scholars and savants who commented in detail on religious matters as well as those of science.

Proponents of wider religious toleration—and a sceptical line on many traditional beliefs—argued with increasing success for changes of attitude in many areas (including discrediting the False Decretals and the legend of Pope Joan, magic and witchcraft, millennialism and extremes of anti-Catholic propaganda, and toleration of Jews in society).

Contention between Catholic and Protestant matters gave rise to a substantial polemical literature, written both in Latin to appeal to international opinion among the educated, and in vernacular languages.

The major debates between Protestants and Catholics proving inconclusive, and theological issues within Protestantism being divisive, there was also a return to the Irenicism: the search for religious peace.

[5] Accusations of heresy, whether the revival of Late Antique debates such as those over Pelagianism and Arianism or more recent views such as Socinianism in theology and Copernicanism in natural philosophy, continued to play an important part in intellectual life.

In reaction, scholars such as Cosimo Boscaglia[6] maintained that the motion of the Earth and immobility of the Sun were heretical, as they contradicted some accounts given in the Bible as understood at that time.

The Protestant lands at the beginning of the 17th century were concentrated in Northern Europe, with territories in Germany, Scandinavia, England, Scotland, and areas of France, the Low Countries, Switzerland, Kingdom of Hungary and Poland.

Heavy fighting, in some cases a continuation of the religious conflicts of the previous centuries, was seen, particularly in the Low Countries and the Electorate of the Palatinate (which saw the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War).

Within Calvinism an important split occurred with the rise of Arminianism; the Synod of Dort of 1618–19 was a national gathering but with international repercussions, as the teaching of Arminius was firmly rejected at a meeting to which Protestant theologians from outside the Netherlands were invited.

This successful, though initially quite difficult, colony marked the beginning of the Protestant presence in America (the earlier French, Spanish and Portuguese settlements were Catholic).

[8] Toward the latter part of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XI viewed the increasing Turkish attacks against Europe, which were supported by France, as the major threat for the Church.

Later waves of colonial expansion such as the struggle for India, by the Dutch, England, France, Germany, Russia and Spanish led to Christianization beyond Asia, such as Philippines.

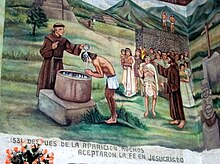

During the Age of Discovery, the Roman Catholic Church established a number of Missions in the Americas and other colonies in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the indigenous peoples.

Following Susenyos' abdication, his son and successor Fasilides expelled archbishop Afonso Mendes and his Jesuit brethren in 1633, then in 1665 ordered the remaining religious writings of the Catholics burnt.

[16] Including representatives of the Greek and Slavic Churches, it condemned the Calvinist teachings ascribed to Cyril Lucaris and ratified (a somewhat amended text of) Peter Mogila's Expositio fidei (Statement of Faith, also known as the Orthodox Confession), a description of Christian orthodoxy in a question and answer format.