Chukat

[2] Jews also read the first part of the parashah, Numbers 19:1–22, in addition to the regular weekly Torah portion, on the Sabbath after Purim, called Shabbat Parah.

[3] In the first reading, God told Moses and Aaron to instruct the Israelites regarding the ritual law of the Red Cow (פָרָה אֲדֻמָּה, parah adumah) used to create the water of lustration.

[24] But God told Moses and Aaron: "Because you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people, therefore you shall not lead this congregation into the land that I have given them.

[38] In the seventh reading, the Israelites sent messengers to Sihon, king of the Amorites, asking that he allow them to pass through his country, without entering the fields or vineyards, and without drinking water from wells.

In Leviticus 21:1–5, God instructed Moses to direct the priests not to allow themselves to become defiled by contact with the dead, except for a mother, father, son, daughter, brother, or unmarried sister.

An episode in the journey like Numbers 20:2–13 is recorded in Exodus 17:1–7, when the people complained of thirst and contended with God, Moses struck the rock with his rod to bring forth water, and the place was named Massah and Meribah.

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[47] Josephus told that after having completed her fortieth year in the wilderness, Miriam died (as reported in Numbers 20:1).

Johanan bar Nappaha said in the name of Rabbi Bana'ah that the Torah was transmitted in separate scrolls, as Psalm 40:8 says, "Then said I, 'Lo I am come, in the roll of the book it is written of me.'"

The idolater explained how, in such a case, they would bring roots, make them smoke under the madman, sprinkle water on the man, and the demon would flee.

Rabbi Eliezer ruled it valid, for Deuteronomy 23:19 states, "You shall not bring the hire of a harlot or the price of a dog into the house of the Lord your God," the Red Cow was not brought into the Temple.

[70] Rabbi Eliezer noted that both Leviticus 16:27 (regarding burning the Yom Kippur sin offerings) and Numbers 19:3 (concerning slaughtering the Red Cow) say "outside the camp."

[71] Rabbi Isaac contrasted the Red Cow in Numbers 19:3–4 and the bull that the High Priest of Israel brought for himself on Yom Kippur in Leviticus 16:3–6.

The Gemara taught that Rav, on the other hand, explained the words "and he shall slay it before him" in Numbers 19:3 to enjoin Eleazar not to divert his attention from the slaughter of the Red Cow.

In contrast, the Gemara posited that Eleazar might not have needed to pay close attention to the casting in of cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet, because they were not part of the Red Cow itself.

Rami bar Ḥama objected that the thread of the Red Cow required a certain weight (to be cast into the flames, as described in Numbers 19:6).

This was so that the priest who burned the Red Cow, while standing on the top of the Mount of Olives, might see the door of the main Temple building when he sprinkled the blood.

[91] The Mishnah taught that when the priest had finished the sprinkling, he wiped his hand on the body of the cow, climbed down, and kindled the fire with wood chips.

[106] Rabbi Joshua ben Kebusai taught that all his days he had read the words "and the clean person shall sprinkle upon the unclean" in Numbers 19:19 and only discovered its meaning from the storehouse of Yavneh.

"[119] Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar taught that Moses and Aaron died because of their sin, as Numbers 20:12 reports God told them, "Because you did not believe in Me .

The midrash taught that it on this account that Deuteronomy 33:8 praises Aaron, saying, "And of Levi he said: 'Your Thummim and your Urim be with your holy one, whom you proved at Massah, with whom you strove at the waters of Meribah.

[123] A midrash noted the use of the verb "take" (קַח, kach) in Numbers 20:25 and interpreted it to mean that God instructed Moses to take Aaron with comforting words.

The midrash taught that Moses was afraid, as he thought that perhaps the Israelites had committed a trespass in the war against Sihon or had soiled themselves by the commission of some transgression.

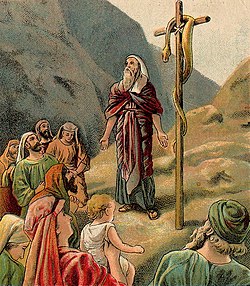

[134] Reading Numbers 21:7, the midrash told that the people realized that they had spoken against Moses and prostrated themselves before him and beseeched him to pray to God on their behalf.

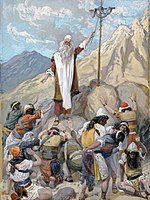

"[135] The Mishnah taught that the brass serpent of Numbers 21:8–9 effected its miraculous cure because when the Israelites directed their thoughts upward and turned their hearts to God they were healed, but otherwise they perished.

Interpreting the words, "Who dwelt at Heshbon," the midrash taught that had Sihon and his armies remained in different towns, the Israelites would have worn themselves out conquering them all.

[140] The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[141] The Zohar taught that Numbers 19:2, "a red heifer, faultless, wherein is no blemish, and upon which never came yoke," epitomized the four Kingdoms foretold in Daniel 8.

Horn Prouser suggested that this verbal coincidence may intimate that Moses' behavior had as much to do with the loss of Miriam reported in Numbers 20:1 as with his frustration with the Israelite people.

Horn Prouser suggested that when faced with the task of producing water, Moses recalled his older sister, his co-leader, and the clever caretaker who guarded him at the Nile.

Excavations at Tel Hesban south of Amman, the location of ancient Heshbon, showed that there was no Late Bronze city, not even a small village, there.

And Finkelstein and Silberman noted that according to the Bible, when the children of Israel moved along the Transjordanian plateau they met and confronted resistance not only in Moab but also from the full-fledged states of Edom and Ammon.