Church window

From the beginning, Christian churches, in contrast to the ancient temples, were intended to be places for the assembling of the faithful.

The temperament of the people of the East and of the South where Christian houses of worship first appeared required the admission of much light by large openings in the walls, that is, by windows.

In Western Europe, or rather in the countries under Roman influence, the places where the windows existed on the side aisles can no longer be identified with absolute certainty, owing to the chapels and additions that were later frequently built.

In the East, however, where it was customary to select isolated sites for church buildings large windows were the rule.

Of that troublous period which extended to the time of Charlemagne and later until the beginning of Romanesque art, few monuments remain that give a clear conception of the window architecture then in vogue.

According to Haupt's researches, the windows of the earliest Germanic churches had a round arch above, which was generally a hollowed stone.

Up to the twelfth century the windows of the Romanesque churches had small openings for light, a sloping intrados, and an inclined sill.

Gothic art adopted this framework, merely changing the round arch into a pointed one, and later replacing the rectangular intervals of the intrados by flutings.

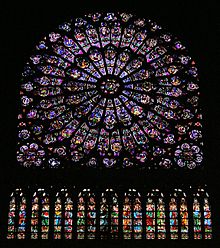

Tracery is formed by setting together separate parts of a circle called foils; their points of contact are named cusps.

Still light openings with slender connexions between them and enclosed in rectangular frames are to found in houses built of stone, particularly in the late Renaissance.

The framing which the Renaissance had given the windows remained customary during the Baroque period, but in agreement with the entire development of the style they were augmented, were more artificial, and had less repose.