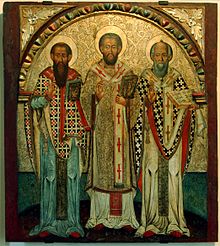

Church Fathers

[4][5][better source needed] Some, such as Origen and Tertullian, made major contributions to the development of later Christian theology, but certain elements of their teaching were later condemned.

The Apostolic Fathers were Christian theologians who lived in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, who are believed to have personally known some of the Twelve Apostles, or to have been significantly influenced by them.

The story of his martyrdom describes how the fire built around him would not burn him, and that when he was stabbed to death, so much blood issued from his body that it quenched the flames around him.

Clement opposed Gnosticism, and yet used some of its terminology; for instance, he valued gnosis that with communion for all people could be held by common Christians.

"[25] Due to his teaching on salvation and divine judgement in passages such as Paedagogus 1.8 and Stromata 7.2, Clement is often regarded as one of the first Christian universalists.

[9] He at times employed an allegorical hermeneutic in his interpretation of the Old Testament, and was partly influenced by Stoic, Neo-Pythagorean, and Platonist thought.

[9] Like Plotinus, he has been thought to believe that the soul passes through successive stages before incarnation as a human and after death, eventually reaching God.

[29] Yet Origen did suggest, based on 1 Corinthians 15:22–28, that all creatures, possibly including even the fallen angels, will eventually be restored and reunited to God when evil is finally eradicated.

Origen's various writings were interpreted by some to imply a hierarchical structure in the Trinity, the temporality of matter, "the fabulous preexistence of souls", and "the monstrous restoration which follows from it."

They argued that Christian faith, while it was against many of the ideas of Plato and Aristotle (and other Greek philosophers), was an almost scientific and distinctive movement with the healing of the soul of man and his union with God at its center.

John Chrysostom (c. 347 – c. 407), archbishop of Constantinople, is known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking; his denunciation of abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and political leaders, recorded sermons and writings making him the most prolific of the eastern fathers, and his ascetic sensibilities.

Chrysostom is also noted for eight of his sermons that played a considerable part in the history of Christian antisemitism, diatribes against Judaizers composed while a presbyter in Antioch, which were extensively exploited and misused by the Nazis in their ideological campaign against the Jews.

[35][36] Patristic scholars such as Robert L Wilken point out that applying modern understandings of antisemitism back to Chrysostom is anachronistic due to his use of the Psogos.

Such principles are explicit in the handbooks of the rhetors, but an interesting passage from the church historian Socrates, writing in the mid-fifth century, shows that the rules for invective were simply taken for granted by men and women of the late Roman world.

The sermon made a deep impression, and Theodosius, who had sat at the feet of Ambrose and Gregory Nazianzus, declared that he had never met with such a teacher (John of Antioch, ap.

His Christological positions eventually resulted in his torture and exile, soon after which he died; however, his theology was vindicated by the Third Council of Constantinople, and he was venerated as a saint soon after his death.

A polymath whose fields of interest and contribution included law, theology, philosophy, and music, he was given the by-name of Chrysorrhoas (Χρυσορρόας, literally "streaming with gold", i.e. "the golden speaker").

[47][48] Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus (c. 155 – c. 222), who was converted to Christianity before 197, was a prolific writer of apologetic, theological, controversial and ascetic works.

[51] He is said to have introduced the Latin term trinitas with regard to the Divine (Trinity) to the Christian vocabulary[52] (but Theophilus of Antioch had already written of "the Trinity, of God, and His Word, and His Wisdom", which is similar but not identical to the Trinitarian wording),[53] and also probably the formula "three Persons, one Substance" as the Latin "tres Personae, una Substantia" (itself from the Koine Greek "τρεῖς ὑποστάσεις, ὁμοούσιος; treís hypostasis, Homoousios"), and also the terms vetus testamentum (Old Testament) and novum testamentum (New Testament).

In his Apologeticus, he was the first Latin author who qualified Christianity as the vera religio, and systematically relegated the classical Roman imperial religion and other accepted cults to the position of mere "superstitions".

He also wrote in defense of the Roman See's authority, and inaugurated use of Latin in the Mass, instead of the Koine Greek that was still being used throughout the Church in the west in the liturgy.

In his early life, Augustine read widely in Greco-Roman rhetoric and philosophy, including the works of Platonists such as Plotinus.

[9] Augustine's work defined the start of the medieval worldview, an outlook that would later be firmly established by Pope Gregory the Great.

The Visigothic legislation which resulted from these councils is regarded by modern historians as exercising an important influence on the beginnings of representative government.

Aphrahat (c. 270 – c. 345 was a Syriac-Christian author of the 3rd century from the Adiabene region of Northern Mesopotamia, which was within the Persian Empire, who composed a series of twenty-three expositions or homilies on points of Christian doctrine and practice.

Called the Persian Sage (Syriac: ܚܟܝܡܐ ܦܪܣܝܐ, ḥakkîmâ p̄ārsāyā), Aphrahat witnesses to the concerns of the early church beyond the eastern boundaries of the Roman Empire.

Isaac is remembered for his spiritual homilies on the inner life, which have a human breadth and theological depth that transcends the Nestorian Christianity of the Church to which he belonged.

On account of their proximity to ancient sources and particular way of doing theology, John of Damascus and Bernard of Clairvaux are among those considered to be the last of the Church Fathers.

[68] The original Lutheran Augsburg Confession of 1530 and the later Formula of Concord of 1576–1584, both begin with the mention of the doctrine professed by the Fathers of the First Council of Nicaea.

Even when a particular Protestant confessional formula does not mention the Nicene Council or its creed, its doctrine is nonetheless always asserted, as, for example, in the Presbyterian Westminster Confession of 1647.