Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds

Recent studies by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scientists, working in cooperation with the National Park Service to better understand volcanic hazards in the Lassen area, have firmly established that Cinder Cone was formed during two eruptions that occurred in the 1650s.

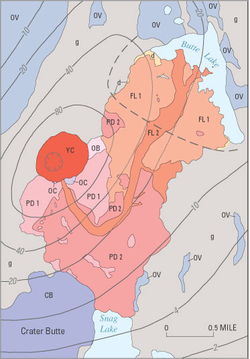

[3] Nearby Snag Lake formed when lava known as the Painted Dunes flows dammed the Grassy Creek stream, which is fed by water from the central plateau of the national park area.

Butte Lake is the sole remaining fragment of a much larger body of water filled with lava during Cinder Cone's eruptive period.

The lava flows and scorias at the volcano closely resemble each other despite distinct chemical compositions, forming dark, fine-grained rocks, with a few visible crystals of the minerals olivine, plagioclase, and quartz.

The second group, erupted later and comparatively rich in titanium, consists of the large, younger scoria cone, the upper part of the ash layer, and the two Fantastic Lava Beds flows.

[4] An unusual characteristic of the Fantastic Lava Beds is the presence of anomalous quartz crystal xenocrysts (foreign bodies in igneous rock).

[9] After traveling through Northern California in the spring of 1851, two gold prospectors reported seeing an erupting volcano that "threw up fire to a terrible height"[4] and that they had walked for 10 mi (16 km) over rocks that burned through their boots.

[5] During the early 1870s, medical doctor and amateur scientist H. W. Harkness from San Francisco, California, visited the Cinder Cone area.

The first such report, which was published in the August 21, 1850, edition of the Daily Pacific News (a San Francisco newspaper), cited an unnamed observer who claimed to have seen "burning lava still running down the sides" at Cinder Cone.

[5] In 1859, the San Francisco Times published an article with testimony from Wozencraft and a companion in which they claimed to have seen flames in the sky from a volcanic eruption from a location west of the Lassen area.

Poking fun at Wozencraft's claims, the Shasta Republican wrote several times throughout April 1859 that "the Dr.'s imagination is far more active than any volcano in our County or State.

[12][13] One of the first USGS scientists to study volcanoes, Diller took careful notes on Cinder Cone and interviewed many Native Americans and European trappers and settlers inhabiting the Lassen region during 1850, none of whom remembered volcanic activity there.

[4] They noted that a large, solitary willow bush (Salix scouleriana) near the summit of Cinder Cone had not been destroyed by any eruptive activity.

[16] Using these assumptions and tree-ring measurements, Finch proposed a complex and detailed eruptive chronology for Cinder Cone that spanned nearly 300 years.

As a result, the USGS began reevaluating the risks posed by other potentially active volcanoes in the Cascade Range, including those in Lassen Volcanic National Park.

[4] Through new field and laboratory work and by reinterpreting data from previous studies, USGS scientists have shown that the entire eruptive sequence at Cinder Cone represents a single continuous event.