Cippi of Melqart

They were discovered in the late 17th century, and the identification of their inscription in a letter dated 1694 made them the first Phoenician writing to be identified and published in modern times.

[1] Because they present essentially the same text (with some minor differences), the cippi provided the key to the modern understanding of the Phoenician language.

The tradition that the cippi were found in Marsaxlokk was only inferred by their dedication to Heracles,[n 2] whose temple in Malta had long been identified with the remains at Tas-Silġ.

[n 3] The Grand Master of the Order of the Knights Hospitaller, Fra Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc, presented one of the cippi to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1782.

[n 5] When the Greek inscription was published in the third volume of the Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum in 1853, the cippi were described as discovered in the coastal village of Marsaxlokk.

[15] The attribution to Tas-Silġ was apparently reached by inference, because the candelabra were thought, with some plausibility, to have been dedicated and set up inside the temple of Heracles.

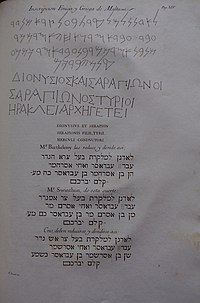

[4][n 6][17] The Phoenician inscription is a Phoenician votive inscription to Melqart, and it reads (from right to left;[n 7] characters inside brackets denote a filled in lacuna): 𐤋𐤀𐤃𐤍𐤍lʾdnn𐤋𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕lmlqrt𐤁𐤏𐤋bʿl𐤑𐤓ṣr𐤀𐤔ʾš𐤍𐤃𐤓ndr𐤋𐤀𐤃𐤍𐤍 𐤋𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕 𐤁𐤏𐤋 𐤑𐤓 𐤀𐤔 𐤍𐤃𐤓lʾdnn lmlqrt bʿl ṣr ʾš ndrTo our lord Melqart, Lord of Tyre, dedicated by𐤏𐤁𐤃[𐤊]ʿbd[k]𐤏𐤁𐤃𐤀𐤎𐤓ʿbdʾsr𐤅𐤀𐤇𐤉wʾḥy𐤀𐤎𐤓𐤔𐤌𐤓ʾsršmr𐤏𐤁𐤃[𐤊] 𐤏𐤁𐤃𐤀𐤎𐤓 𐤅𐤀𐤇𐤉 𐤀𐤎𐤓𐤔𐤌𐤓ʿbd[k] ʿbdʾsr wʾḥy ʾsršmryou[r] servant Abd' Osir and his brother 'Osirshamar𐤔𐤍šn𐤁𐤍bn𐤀𐤎𐤓𐤔𐤌𐤓ʾsršmr𐤁𐤍bn𐤏𐤁𐤃𐤀𐤎𐤓ʿbdʾsr𐤊𐤔𐤌𐤏kšmʿ𐤔𐤍 𐤁𐤍 𐤀𐤎𐤓𐤔𐤌𐤓 𐤁𐤍 𐤏𐤁𐤃𐤀𐤎𐤓 𐤊𐤔𐤌𐤏šn bn ʾsršmr bn ʿbdʾsr kšmʿboth sons of 'Osirshamar, son of Abd' Osir, for he heard𐤒𐤋𐤌qlm𐤉𐤁𐤓𐤊𐤌ybrkm [12]𐤒𐤋𐤌 𐤉𐤁𐤓𐤊𐤌qlm ybrkmtheir voice, may he bless them.

[18][n 8]The following is the Greek inscription, a rendering to polytonic and bicameral script and adding spaces, a transliteration including accents, and a translation: ΔιονύσιοςDionýsiosκαὶkaìΣαραπίωνSarapíōnοἱhoiΔιονύσιος καὶ Σαραπίων οἱDionýsios kaì Sarapíōn hoiDionysios and Sarapion, theΣαραπίωνοςSarapíōnosΤύριοιTýrioiΣαραπίωνος ΤύριοιSarapíōnos Týrioisons of Sarapion, Tyrenes,ἩρακλεῖHērakleîἀρχηγέτειarchēgétei [12]Ἡρακλεῖ ἀρχηγέτειHērakleî archēgéteito Heracles the founder.

[19] This identification was on the basis that "Phoenicians" were recorded as ancient inhabitants of Malta by Greek writers Thucydides and Diodorus Siculus.

[n 12] However, the Maltese historian Ciantar claimed that the cippi were discovered in 1732, and placed the discovery in the villa of Abela, which had become a museum entrusted to the Jesuits.

[23][n 14] Copies of the inscriptions, which had been made by Giovanni Uvit in 1687, were sent to Verona to an art historian, poet and Knight Commander in the Hospitaller order, Bartolomeo dal Pozzo.

[n 15] In 1735, Abbé Guyot de Marne, also a Knight Commander of the Maltese Order, published the text again in an Italian journal, the Saggi di dissertazioni accademiche of the Etruscan Academy of Cortona, but did not hypothesise a translation.

[3] In 1772, Francisco Pérez Bayer published a book detailing the previous attempts at understanding the text, and provided his own interpretation and translation.

[2] The term Rosetta stone of Malta has been used idiomatically to represent the role played by the cippi in decrypting the Phoenician alphabet and language.