Circumstellar disc

A circumstellar disc (or circumstellar disk) is a torus, pancake or ring-shaped accretion disk of matter composed of gas, dust, planetesimals, asteroids, or collision fragments in orbit around a star.

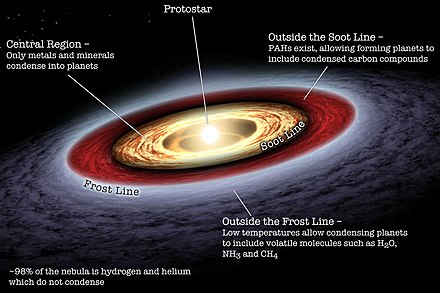

According to the widely accepted model of star formation, sometimes referred to as the nebular hypothesis, a young star (protostar) is formed by the gravitational collapse of a pocket of matter within a giant molecular cloud.

The infalling material possesses some amount of angular momentum, which results in the formation of a gaseous protoplanetary disc around the young, rotating star.

The former is a rotating circumstellar disc of dense gas and dust that continues to feed the central star.

The main accretion phase lasts a few million years, with accretion rates typically between 10−7 and 10−9 solar masses per year (rates for typical systems presented in Hartmann et al.[2]).

Within this disc, the formation of small dust grains made of rocks and ices can occur, and these can coagulate into planetesimals.

If the disc is sufficiently massive, the runaway accretions begin, resulting in the appearance of planetary embryos.

The infall of gas onto a binary system allows the formation of circumstellar and circumbinary discs.

The formation of such a disc will occur for any binary system in which infalling gas contains some degree of angular momentum.

[4] A general progression of disc formation is observed with increasing levels of angular momentum: The indicative timescale that governs the short-term evolution of accretion onto binaries within circumbinary disks is the binary's orbital period

For non-eccentric binaries, accretion variability coincides with the Keplerian orbital period of the inner gas, which develops lumps corresponding to

This corresponds to the apsidal precession rate of the inner edge of the cavity, which develops its own eccentricity

[7] This eccentricity may in turn affect the inner cavity accretion as well as dynamics further out in the disk, such as circumbinary planet formation and migration.

It was originally believed that all binaries located within circumbinary disk would evolve towards orbital decay due to the gravitational torque of the circumbinary disk, primarily from material at the innermost edge of the excised cavity.

The dynamics of orbital evolution depend on the binary's parameters, such as the mass ratio

[4] The majority of these discs form axissymmetric to the binary plane, but it is possible for processes such as the Bardeen-Petterson effect,[8] a misaligned dipole magnetic field[9] and radiation pressure[10] to produce a significant warp or tilt to an initially flat disk.

Strong evidence of tilted disks is seen in the systems Her X-1, SMC X-1, and SS 433 (among others), where a periodic line-of-sight blockage of X-ray emissions is seen on the order of 50–200 days; much slower than the systems' binary orbit of ~1 day.

[11] The periodic blockage is believed to result from precession of a circumprimary or circumbinary disk, which normally occurs retrograde to the binary orbit as a result of the same differential torque which creates spiral density waves in an axissymmetric disk.

Evidence of tilted circumbinary disks can be seen through warped geometry within circumstellar disks, precession of protostellar jets, and inclined orbits of circumplanetary objects (as seen in the eclipsing binary TY CrA).

[5] For disks orbiting a low secondary-to-primary mass ratio binary, a tilted circumbinary disc will undergo rigid precession with a period on the order of years.

Stages include the phases when the disc is composed mainly of submicron-sized particles, the evolution of these particles into grains and larger objects, the agglomeration of larger objects into planetesimals, and the growth and orbital evolution of planetesimals into the planetary systems, like our Solar System or many other stars.

Together with information about the mass of the central star, observation of material dissipation at different stages of a circumstellar disc can be used to determine the timescales involved in its evolution.

Mechanisms like decreasing dust opacity due to grain growth,[20] photoevaporation of material by X-ray or UV photons from the central star (stellar wind),[21] or the dynamical influence of a giant planet forming within the disc[22] are some of the processes that have been proposed to explain dissipation.

[24] Studies of older debris discs (107 - 109 yr) suggest dust masses as low as 10−8 solar masses, implying that diffusion in outer discs occurs on a very long timescale.

[25] As mentioned, circumstellar discs are not equilibrium objects, but instead are constantly evolving.

Beta Pictoris or AU Microscopii) and face-on disks (e.g. IM Lupi or AB Aurigae) require a coronagraph, adaptive optics or differential images to take an image of the disk with a telescope.

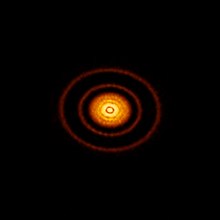

These optical and infrared observations, for example with SPHERE, usually take an image of the star light being scattered on the surface of the disk and trace small micron-sized dust particles.

Radio arrays like ALMA on the other hand can map larger millimeter-sized dust grains found in the mid-plane of the disk.

[28] Radio arrays like ALMA can also detect narrow emission from the gas of the disk.

[29] In some cases an edge-on protoplanetary disk (e.g. CK 3[30][31] or ASR 41[32]) can cast a shadow onto the surrounding dusty material.