Citizenship

Since then states have expanded the status of citizenship to most of their national people, while the extent of citizen rights remain contested.

[10] As such nationality in international law can be called and understood as citizenship,[10] or more generally as subject or belonging to a sovereign state, and not as ethnicity.

Examples of national symbols includes the Ghanaian flag, coat of arms, money, and state sword.

Many thinkers such as Giorgio Agamben in his work extending the biopolitical framework of Foucault's History of Sexuality in the book, Homo Sacer,[17] point to the concept of citizenship beginning in the early city-states of ancient Greece, although others see it as primarily a modern phenomenon dating back only a few hundred years and, for humanity, that the concept of citizenship arose with the first laws.

It was necessary to fit Aristotle's definition of the besouled (the animate) to obtain citizenship: neither the sacred olive tree nor spring would have any rights.

Historian Geoffrey Hosking in his 2005 Modern Scholar lecture course suggested that citizenship in ancient Greece arose from an appreciation for the importance of freedom.

[23][24] The first form of citizenship was based on the way people lived in the ancient Greek times, in small-scale organic communities of the polis.

These small-scale organic communities were generally seen as a new development in world history, in contrast to the established ancient civilizations of Egypt or Persia, or the hunter-gatherer bands elsewhere.

Roman citizenship was no longer a status of political agency, as it had been reduced to a judicial safeguard and the expression of rule and law.

[25] Rome carried forth Greek ideas of citizenship such as the principles of equality under the law, civic participation in government, and notions that "no one citizen should have too much power for too long",[26] but Rome offered relatively generous terms to its captives, including chances for lesser forms of citizenship.

[30] During the European Middle Ages, citizenship was usually associated with cities and towns (see medieval commune), and applied mainly to middle-class folk.

[32] And being a citizen often meant being subject to the city's law in addition to having power in some instances to help choose officials.

[20] From 1790 until the mid-twentieth century, United States law used racial criteria to establish citizenship rights and regulate who was eligible to become a naturalized citizen.

[36] The Naturalization Act of 1790, the first law in U.S. history to establish rules for citizenship and naturalization, barred citizenship to all people who were not of European descent, stating that "any alien being a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years, maybe admitted to becoming a citizen thereof.

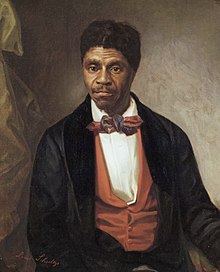

In 1857, these laws were upheld in the US Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford, which ruled that "a free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a 'citizen' within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States," and that "the special rights and immunities guaranteed to citizens do not apply to them.

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act explicitly denied naturalization rights to all people of Chinese origin, while subsequent acts passed by the US Congress, such as laws in 1906, 1917, and 1924, would include clauses that denied immigration and naturalization rights to people based on broadly defined racial categories.

[41] Supreme Court cases such as Ozawa v. the United States (1922) and U.S. v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), would later clarify the meaning of the phrase "free white persons," ruling that ethnically Japanese, Indian, and other non-European people were not "white persons", and were therefore ineligible for naturalization under U.S. law.

"[44] It recognized "the equal rights of all citizens, irrespective of their racial or national connections" and declared oppression of any minority group or race "to be contrary to the fundamental laws of the Republic."

The 1918 constitution also established the right to vote and be elected to soviets for both men and women "irrespective of religion, nationality, domicile, etc.

Nazism, the German variant of twentieth-century fascism, classified inhabitants of the country into three main hierarchical categories, each of which would have different rights in relation to the state: citizens, subjects, and aliens.

Citizenship was conferred only on males of German (or so-called "Aryan") heritage who had completed military service, and could be revoked at any time by the state.

[20] In China, for example, there is a cultural politics of citizenship which could be called "peopleship", argued by an academic article.

Citizenship as a concept is generally hard to isolate intellectually and compare with related political notions since it relates to many other aspects of society such as the family, military service, the individual, freedom, religion, ideas of right, and wrong, ethnicity, and patterns for how a person should behave in society.

[23] Some intergovernmental organizations have extended the concept and terminology associated with citizenship to the international level,[58] where it is applied to the totality of the citizens of their constituent countries combined.

Article 18 provided a limited right to free movement and residence in the Member States other than that of which the European Union citizen is a national.

[62] Citizenship of the Mercosur is granted to eligible citizens of the Southern Common Market member states.

By the time children reach secondary education there is an emphasis on such unconventional subjects to be included in an academic curriculum.

The idea behind this model within education is to instill in young pupils that their actions (i.e. their vote) affect collective citizenship and thus in turn them.

The concept of citizenship is criticized by open borders advocates, who argue that it functions as a caste, feudal, or apartheid system in which people are assigned dramatically different opportunities based on the accident of birth.

In 1987, moral philosopher Joseph Carens argued that "citizenship in Western liberal democracies is the modern equivalent of feudal privilege—an inherited status that greatly enhances one's life chances.