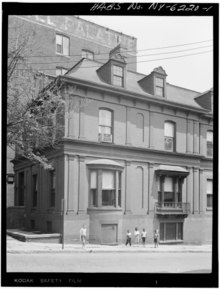

City Club (Newburgh, New York)

The City Club, known also as the William Culbert House, is a historic ruin at the corner of Grand and 2nd Streets in Newburgh, New York.

Designed in the early 1850s by Calvert Vaux and Andrew Jackson Downing, the house survived Urban Renewal efforts but succumbed to fire in 1981.

Plans have been made since its destruction to reconstruct the interior, a project often paired with restoration of the nearby Dutch Reformed Church, but none have ever been executed.

[2] Culbert studied under Professor of Surgery at the university, Dr. Valentine Mott, who at the time was deemed one of world's most esteemed surgeons.

Powell helped establish Newburgh as a shipping center, adding docks to village's bustling port for his freighting business.

[6] Beginning in 1823, Thomas continued the mildly lucrative mercantile business he had begun with his brother, eventually amassing a fortune and ordering the construction of a steamboat fleet.

[5] Thomas and Mary had one son, Robert Ludlow Powell (1805 — 1833), who married Louisa A. Orso (1806 — 1896), the parents of Henrietta and several daughters.

The exact date of erection is unknown, but city historian Helen VerNooy Gearn first estimated 1852 or earlier in conjunction with the wedding.

[10] The house's corner lot inherently made planning its street-facing side crucial, as it needed to be congruous with the slope and also keen to the eye.

Of Culbert's medical career, John J. Nutt remarked that he was:"Carefully educated, possessed of an unusually clear and logical mind, fully alive to every advance in his profession and allowing no one dogma to fetter his judgment — he was a physician in the broadest sense of the term.

Ever true to the interests of his patients, Dr. Culbert soon won and maintained to the time of his death the reputation of an accurate diagnostician, an independent thinker and an unusually practical and successful prescriber.

One upstairs office,[13] serving as chambers for the justice of the State Supreme Court, Ninth Judicial District, underwent a remodeling to hold a law library.

[16] This library was originally to serve the purpose of the Newburgh Bar Association as a private, non-profit organization, but soon after came under state control, which assumed costs of operation.

[17] With the surge of Urban Renewal demolition projects below Grand Street in 1970, the Newburgh URA finished the year by razing the Club's neighbor, the defunct Palatine Hotel.

On February 11, 1971, the legislature set a vote to remove the library, a measure sponsored by George R. Bartlett, Jr., R-Walden, chairman of the County Protective Educational Services Committee.

[23] Architectural firm Marvel, Whitfield and Remick, based in Newburgh, were responsible for the tentative plans, commissioned originally for $16,000 by Mills.

[23] At the February convening of the legislature, Ahearn arrived with a bargain, claiming that Newburgh mayor George McKneally would be able to convince the city council to pay $5,000 rent to keep the law library where it was.

[19] Out of the URA's hands, the Board of Education undertook responsibility for the City Club, perceived as the monitor for all Courthouse Square dealings.

"[29] In its place, they wanted an unobstructed view of the library, and planned to landscape the 45" x 122" land with taxpayer dollars, in addition to the $30,000 demolition cost.

With the help of Lyon, Pyburn also formed the general Committee for Saving the City Club, which received anonymous support via donations.

In October 1975, Pyburn and Terri Holbert, representing the Greater Newburgh Arts Council, urged the city to apply for $14,000 of federal funding to rescue the building.

The exact reason for the permit at this date is unclear, but likely attributed to pressure from the Board of Education, who would want to begin landscaping in the spring to celebrate the opening of the new library.

[31] City Club members were reluctant to let the building fall, but sale of the land plot to the Board of Education for $30,000 would be enough to liquidate their debts.

The library was given 30 days to remove its contents, which were placed temporarily in the unfinished new courthouse addition, where they stayed inaccessible, frustrating lawyers.

[32] Steegmuller expressed regret for the situation, and was not entirely appreciative of Pyburn and other preservationists, who he felt arrived at the "last minute",[32] as he and Ahearn had stressed the building's historic significance years earlier.

At a Board Meeting on January 27, 1976, president Murray Cohen gave Thompson six months to restore the building, notifying him it would be torn down if he did not deliver satisfactory results.

[33] While he began to plan his restoration, Cohen and school trustees contacted lawyers to ensure the building would not be protected by historic preservation laws.