Civil Rights Cases

The holding that the Thirteenth Amendment did not empower the federal government to punish racist acts done by private citizens would be overturned by the Supreme Court in the 1968 case Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.

During Reconstruction, Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which entitled everyone to access accommodation, public transport, and theaters regardless of race or color.

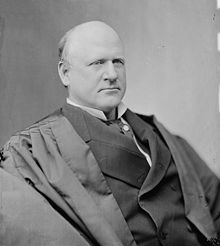

Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lone dissenter in the case, writing that the "substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism."

The decision ushered in the widespread segregation of blacks in housing, employment, and public life that confined them to second-class citizenship throughout much of the United States until the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960s.

Black American plaintiffs, in five cases from lower courts,[2] sued theaters, hotels, and transit companies that refused to admit them, or had excluded them from "white only" facilities.

The Civil Rights Act of 1875 had been passed by Congress and entitled everyone to access accommodation, public transport, and theaters regardless of race or color.

To implement the principles in the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress had specified that people could not be discriminated against on grounds of race or color in access to services offered to the general public.

Innkeepers and public carriers, by the laws of all the states, so far as we are aware, are bound, to the extent of their facilities, to furnish proper accommodation to all unobjectionable persons who in good faith apply for them.

Mere discriminations on account of race or color were not regarded as badges of slavery ...Justice Harlan dissented against the Court's narrow interpretation of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments for all five of the cases.

He argued Congress was attempting to overcome the refusal of the states to protect the rights denied to African Americans that white citizens took as their birthright.

& P. 213)[5] who had no right to deny to anyone "conducting himself in a proper manner" admission to his inn; and that public amusements are maintained under a license coming from the State.

He also found that the lack of protection from the 1875 Civil Rights Act would result in the violation of the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, largely on the same grounds.

Harlan J would have held the Civil Rights Act of 1875 valid, because people were left "practically at the mercy of corporations and individuals wielding power under public authority".

I mean only, in this form, to express an earnest conviction that the court has departed from the familiar rule requiring, in the interpretation of constitutional provisions, that full effect be given to the intent with which they were adopted.

The court adjudges that congress is without power, under either the thirteenth or fourteenth amendment, to establish such regulations, and that the first and second sections of the statute are, in all their parts, unconstitutional and void.

'Personal liberty consists,' says Blackstone, 'in the power of locomotion, of changing situation, or removing one's person to whatever place one's own inclination may direct, without restraint, unless by due course of law.'

In the Munn Case the question was whether the state of Illinois could fix, by law, the maximum of charges for the storage of grain in certain warehouses in that state—the private property of individual citizens.

It is fundamental in American citizenship that, in respect of such rights, there shall be no discrimination by the state, or its officers, or by individuals, or corporations exercising public functions or authority, against any citizen because of his race or previous condition of servitude.

And in Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 344, the emphatic language of this court is that 'one great purpose of these amendments was to raise the colored race from that condition of inferiority and servitude in which most of them had previously stood, into perfect equality of civil rights with all other persons within the jurisdiction of the states.'

'The sound construction of the constitution,' said Chief Justice MARSHALL, 'must allow to the national legislature that discretion, with respect to the means by which the powers it confers are to be carried into execution, which will enable that body to perform the high duties assigned to it in the manner most beneficial to the people.

It would never occur to any one that the presence of a colored citizen in a court-house or court-room was an invasion of the social rights of white persons who may frequent such places.

The difficulty has been to compel a recognition of their legal right to take that rank, and to secure the enjoyment of privileges belonging, under the law, to them as a component part of the people for whose welfare and happiness government is ordained.

To-day it is the colored race which is denied, by corporations and individuals wielding public authority, rights fundamental in their freedom and citizenship.

The supreme law of the land has decreed that no authority shall be exercised in this country upon the basis of discrimination, in respect of civil rights, against freemen and citizens because of their race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

For the reasons stated I feel constrained to withhold my assent to the opinion of the court.The decision met with public protest across the country, and led to regular "indignation meetings" held in numerous cities.

Furthermore, In the wake of the Supreme Court ruling, the federal government adopted as policy that allegations of continuing slavery were matters whose prosecution should be left to local authorities only – a de facto acceptance that white southerners could do as they wished with the black people in their midst.

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 generally revived the ban on discrimination in public accommodations that was in the Civil Rights Act of 1875, but under the Commerce Clause of Article I instead of the 14th Amendment; the Court held Title II to be constitutional in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S. 241 (1964).